If Mars One makes you skeptical, you might be dead inside—like me

Op-ed: Do we scoff at dreamers because we lack imagination, or are they actually crazy?

Touchstone Pictures

Wanted: Applicants for one-way trip to Mars. Will provide training, supplies, spaceship. Must be OK with being on television. No return option. Survival possible, but not guaranteed.That's an abbreviated version of the pitch Mars One has made, and more than 30,000 people read it and applied for the chance to be permanent Mars residents. It's not my cup of tea—even if the mission were a guaranteed success, I like my comfy life too much to give it up for a chance to live out my days like Dr. Manhattan on the red planet—but the space mission/reality TV show has attracted some passionate followers.

Ars writer Casey Johnston spoke with one of the Mars One applicants, Aaron Hamm (who also is also a member of the Ars OpenForum under the username "Quisquis"), who genuinely believes in the mission of Mars One. Hamm and many other applicants see the chance to live out their lives on Mars as not only a worthwhile step in humankind's exploration of the universe, but also as the fulfillment of a personal dream.

Aaron Hamm, would-be Mars colonist.

"I'm kind of curious what the public is expecting to see at this point," wrote Hamm in a comment to the previously linked Ars story. "Everyone panning the program seems to expect that they should be able to see blueprints and budgets or something." He continued:

Even if Mars One executes exactly as they plan to, no one who isn't intimately involved in the project is going to see that level of detail.I wrote a pretty lengthy response comment, which one of the staff pinned as an editor's choice comment. On reflection, it's worth holding that reaction up to a critical lens: am I just a hopeless doubter, shouting down every non-NASA idea with loud cries of "NO, IT CAN'T BE DONE" without having an appropriately open mind? Or is skepticism at this stage justified?

And I think everyone should take a moment to remember that 10 years before we landed on the Moon, we couldn't even launch a rocket into space...

Ten years before the moon

Ten years prior to Apollo 11's landing, NASA was a fledgling agency, having just barely taken over the United States space launch efforts from its defunct predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. No human being had yet left the Earth, and none would do so for almost two more years. At that point, the idea of putting a human being on another world wasn't really in the national consciousness; the US government was more concerned about the Soviet Union's ability to lob intercontinental ballistic missiles into the middle of the United States—or overfly US territory from orbit with impunity.Ten years later, in the culmination of the greatest engineering effort in the history of the human race, two humans spent a bit over 21 hours on the lunar surface and actually walked around outside their spacecraft for two hours and thirty-six minutes. The running budget of Project Apollo from 1960 to 1969 was $16,130,420,000, so it could be said that every second of that two hours and thirty-six minutes carried an effective cost of about $1,700,000.

Enlarge / Buzz Aldrin's bootprint during Apollo 11 (NASA image AS11-40-5878).

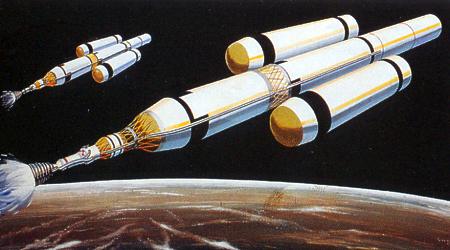

Artist's conception of the 1969 Von Braun Mars Expedition.

But $6 billion still seems a little light.

The right stuff?

The Mars One technology page lays out in broad strokes the vehicles and technology organizers plan to use to reach and explore Mars. The group anticipates saving huge amounts of money by getting spacecraft, people, and supplies up to space as payload on the SpaceX-built Falcon Heavy launch vehicles, which should, if all goes according to plan, be built to NASA's human-rating guidelines and should therefore be "safe" for transporting people in addition to cargo. These plans are obviously predicated on Falcon Heavy being brought into operation on time.By using Dragon capsule variants in a variety of roles, Mars One also removes the need to design a spacecraft or a Mars landing vehicle, saving tremendous amounts of money... possibly. One issue is that there's no acceptable method yet to actually land people on Mars. Parachutes simply don't work—Mars' atmosphere is too thin. The bouncy-ball airbag method used for Mars Pathfinder and the twin Spirit and Opportunity rovers doesn't scale well to living creatures. Curiosity's famous powered skycrane isn't a much of a candidate, either, because every ounce of fuel and skycrane mechanical bits added to the lander is an ounce that cannot be used instead for post-landing supplies for the four Mars One colonists.

A viable option would likely look something like the Apollo-era Lunar Module's powered descent, wherein the LM balanced itself atop its descent engine and decelerated its way down to the surface in a mostly automated fashion. Drastically more sophisticated computers and software would obviate many of the deadly challenges of the Apollo-style powered descent, but it's not nearly as simple as popping a parachute and drifting gently down to the ground.

A

graphical depiction of the Apollo Lunar Module's powered descent to the

lunar surface. A manned martian lander will almost certainly have to

perform a similar landing.

There's another factor that incites skepticism: with one exception, every human being who has walked on another world has been an extremely skilled test pilot or naval aviator (and the one exception, Dr. Harrison Schmidt, was trained and rated on supersonic jets after his acceptance to the astronaut corps). This kind of background made the astronauts not just adept at flying planes and lunar landers, but also powerfully sharp observers and communicators, able to process lots and lots of inputs simultaneously and make extremely quick and informed decisions in response to rapidly changing situations. Beyond being incredible pilots, most were also brilliant—Buzz Aldrin, for example, holds a PhD from MIT in astronautics and his thesis, "Line of Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous," formed the groundwork for much of NASA's rendezvous procedures during Project Gemini.

Enlarge /

This is Buzz Aldrin, aka "Dr. Rendezvous." He basically figured out a

bunch of stuff about how orbits work that NASA still uses to this day.

Also, he will literally punch you in the face if you anger him. (NASA photo AS11-36-5390).

In contrast, Mars One is holding a popularity contest for random Internet applicants, and it wants to sell the TV rights to the training and mission. It doesn't conjure up images of bold exploration so much as it does broken dreams and farce.

The final countdown

Organizers' plans for mission sustainability—and, I'll of course grant that I don't know anything other than what has been publicly released, so maybe they've got a workaround for this—are contingent on other suppliers to provide almost everything material to the mission. Assuming they can vault the initial hurdle and actually set four souls down on Mars, those folks' survival depends on the very, very nascent commercial space industry to keep them from dying a slow death. Maybe that's what it will take to make commercial space travel viable, but I think it's going to come back to that oldest, truest adage of space flight: no bucks, no Buck Rogers.Maybe I'm having such a hard time with it because it seems fantastic and silly, and in real life, fantastic and silly plans usually meet with harsh and unfunny ends; maybe the mention of "reality TV" automatically poisons my entire picture of the project. Maybe I'm just a pessimistic person with a dried-up soul and a hopelessly atrophied sense of wonder. I don't know. I do know that I can't help but see Mars One in comparison to the space race; by the time everything was said and done, the US spent more than $100 billion in 1960s dollars to send the very best people it could find to the moon... and now we're going to canvas the Internet for folks who want to go die on Mars and make a TV show out of it.

It just seems like a ludicrous, impossible project. And not the good kind of impossible project that ends in the triumph of the human spirit overcoming the whatever blah, blah, blah—this seems like the bad kind of impossible project where people wind up dead. I wish Mars One and its applicants luck, but if they pull off even a single launch, I'll eat my hat.

No comments:

Post a Comment