To the National Security Agency analyst writing a briefing to

his superiors, the situation was clear: their current surveillance

efforts were lacking something. The agency's impressive arsenal of cable

taps and sophisticated hacking attacks was not enough. What it really

needed was a horde of undercover Orcs.

That vision of spycraft sparked a concerted drive by the

NSA and its UK sister agency

GCHQ to infiltrate the massive communities playing online

games, according to secret documents disclosed by whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The files were obtained by the Guardian and are being published on Monday in partnership with the

New York Times and

ProPublica.

The

agencies, the documents show, have built mass-collection capabilities

against the Xbox Live console network, which has more than 48 million

players. Real-life agents have been deployed into virtual realms, from

those Orc hordes in World of Warcraft to the human avatars of Second

Life. There were attempts, too, to recruit potential informants from the

games' tech-friendly users.

Online gaming is big business,

attracting tens of millions of users worldwide who inhabit their digital

worlds as make-believe characters, living and competing with the

avatars of other players. What the intelligence agencies feared,

however, was that among these clans of elves and goblins, terrorists

were lurking.

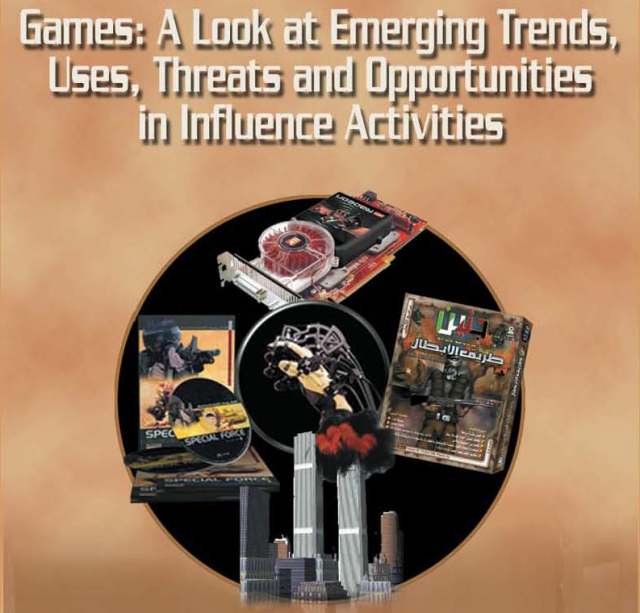

The NSA document, written in 2008 and titled

Exploiting Terrorist Use of Games & Virtual Environments, stressed

the risk of leaving games communities under-monitored, describing them

as a "target-rich communications network" where intelligence targets

could "hide in plain sight".

Games, the analyst wrote, "are an

opportunity!". According to the briefing notes, so many different US

intelligence agents were conducting operations inside games that a

"deconfliction" group was required to ensure they weren't spying on, or

interfering with, each other.

If properly exploited, games could

produce vast amounts of intelligence, according to the NSA document.

They could be used as a window for hacking attacks, to build pictures of

people's social networks through "buddylists and interaction", to make

approaches by undercover agents, and to obtain target identifiers (such

as profile photos), geolocation, and collection of communications.

The

ability to extract communications from talk channels in games would be

necessary, the NSA paper argued, because of the potential for them to

be used to communicate anonymously: Second Life was enabling anonymous

texts and planning to introduce voice calls, while game noticeboards

could, it states, be used to share information on the web addresses of

terrorism forums.

Given that gaming consoles often include voice

headsets, video cameras, and other identifiers, the potential for

joining together biometric information with activities was also an

exciting one.

But the documents contain no indication that the

surveillance ever foiled any terrorist plots, nor is there any clear

evidence that terror groups were using the virtual communities to

communicate as the intelligence agencies predicted.

The operations

raise concerns about the privacy of gamers. It is unclear how the

agencies accessed their data, or how many communications were collected.

Nor is it clear how the NSA ensured that it was not monitoring innocent

Americans whose identity and nationality may have been concealed behind

their virtual avatar.

The California-based producer of World of

Warcraft said neither the NSA nor GCHQ had sought its permission to

gather intelligence inside the game. "We are unaware of any surveillance

taking place," said a spokesman for Blizzard Entertainment. "If it was,

it would have been done without our knowledge or permission."

Microsoft

declined to comment on the latest revelations, as did Philip Rosedale,

the founder of Second Life and former CEO of Linden Lab, the game's

operator. The company's executives did not respond to requests for

comment.

The NSA declined to comment on the surveillance of games.

A spokesman for GCHQ said the agency did not "confirm or deny" the

revelations but added: "All GCHQ's work is carried out in accordance

with a strict legal and policy framework which ensures that its

activities are authorised, necessary and proportionate, and there is

rigorous oversight, including from the secretary of state, the

interception and intelligence services commissioners and the

intelligence and security committee."

Though the spy agencies

might have been relatively late to virtual worlds and the communities

forming there, once the idea had been mooted, they joined in

enthusiastically.

In May 2007, the then-chief operating officer of

Second Life gave a "brown-bag lunch" address at the NSA explaining how

his game gave the government "the opportunity to understand the

motivation, context and consequent behaviours of non-Americans through

observation, without leaving US soil".

One problem the paper's

unnamed author and others in the agency faced in making their case – and

avoiding suspicion that their goal was merely to play computer games at

work without getting fired – was the difficulty of proving terrorists

were even thinking about using games to communicate.

A 2007

invitation to a secret internal briefing noted "terrorists use online

games – but perhaps not for their amusement. They are suspected of using

them to communicate secretly and to transfer funds." But the agencies

had no evidence to support their suspicions.

The same still seemed

to hold true a year later, albeit with a measure of progress: games

data that had been found in connection with internet protocol addresses,

email addresses and similar information linked to terrorist groups.

"Al-Qaida

terrorist target selectors and … have been found associated with Xbox

Live, Second Life, World of Warcraft, and other GVEs [games and virtual

environments]," the document notes. "Other targets include Chinese

hackers, an Iranian nuclear scientist, Hizballah, and Hamas members."

However,

that information wasn not enough to show terrorists are hiding out as

pixels to discuss their next plot. Such data could merely mean someone

else in an internet cafe was gaming, or a shared computer had previously

been used to play games.

That lack of knowledge of whether

terrorists were actually plotting online emerges in the document's

recommendations: "The amount of GVEs in the world is growing but the

specific ones that CT [counter-terrorism] needs to be methodically

discovered and validated," it stated. "Only then can we find evidence

that GVEs are being used for operational uses."

Not actually

knowing whether terrorists were playing games was not enough to keep the

intelligence agencies out of them, however. According to the document,

GCHQ had already made a "vigorous effort" to exploit games, including

"exploitation modules" against Xbox Live and World of Warcraft.

That

effort, based in the agency's New Mission Development Centre in the

Menwith Hill air force base in North Yorkshire, was already paying

dividends by May 2008.

At the request of GCHQ, the NSA had begun a

deliberate effort to extract World of Warcraft metadata from their

troves of intelligence, and trying to link "accounts, characters and

guilds" to Islamic extremism and arms dealing efforts. A later memo

noted that among the game's active subscribers were "telecom engineers,

embassy drivers, scientists, the military and other intelligence

agencies".

The UK agency did not stop at World of Warcraft: by

September a memo noted GCHQ had "successfully been able to get the

discussions between different game players on Xbox Live".

Meanwhile,

the FBI, CIA, and the Defense Humint Service were all running human

intelligence operations – undercover agents – within Second Life. In

fact, so crowded were the virtual worlds with staff from the different

agencies, that there was a need to try to "deconflict" their efforts –

or, in other words, to make sure each agency wasn't just duplicating

what the others were doing.

By the end of 2008, such efforts had

produced at least one usable piece of intelligence, according to the

documents: following the successful takedown of a website used to trade

stolen credit card details, the fraudsters moved to Second Life – and

GCHQ followed, having gained their first "operational deployment" into

the virtual world. This, they noted, put them in touch with an "avatar

[game character] who helpfully volunteered information on the target

group's latest activities".

Second Life continued to occupy the

intelligence agencies' thoughts throughout 2009. One memo noted the

game's economy was "essentially unregulated" and so "will almost

certainly be used as a venue for terrorist laundering and will, with

certainty, be used for terrorist propaganda and recruitment".

In

reality, Second Life's surreal and uneven virtual world failed to

attract or maintain the promised mass-audience, and attention (and its

user base) waned, though the game lives on.

The agencies had other

concerns about games, beyond their potential use by terrorists to

communicate. Much like the pressure groups that worry about the effect

of computer games on the minds of children, the NSA expressed concerns

that games could be used to "reinforce prejudices and cultural

stereotypes", noting that Hezbollah had produced a game called Special

Forces 2.

According to the document, Hezbollah's "press section

acknowledges [the game] is used for recruitment and training", serving

as a "radicalising medium" with the ultimate goal of becoming a "suicide

martyr". Despite the game's disturbing connotations, the "fun factor"

of the game cannot be discounted, it states. As Special Forces 2 retails

for $10, it concludes, the game also serves to "fund terrorist

operations".

Hezbollah is not, however, the only organisation to

have considered using games for recruiting. As the NSA document

acknowledges: they got the idea from the US army.

"America's Army

is a US army-produced game that is free [to] download from its

recruitment page," says the NSA, noting the game is "acknowledged to be

so good at this the army no longer needs to use it for recruitment, they

use it for training".

For

the past few months City of London Police have been working together

with the music and movie industries to tackle sites that provide

unauthorized access to copyrighted content.

For

the past few months City of London Police have been working together

with the music and movie industries to tackle sites that provide

unauthorized access to copyrighted content.