http://www.thembj.org/2012/07/diy-musicians-alone-together/

One of the music community’s most popular – and romantic – memes is that technology

has leveled the playing field to the point that musicians can “do it

all themselves”. Why sign with a record label when it’s cheap and easy

to get your music on iTunes? Why hire a publicist when you’ve got

Twitter? Who needs a booking agent when you can create a following on

YouTube?

One of the music community’s most popular – and romantic – memes is that technology

has leveled the playing field to the point that musicians can “do it

all themselves”. Why sign with a record label when it’s cheap and easy

to get your music on iTunes? Why hire a publicist when you’ve got

Twitter? Who needs a booking agent when you can create a following on

YouTube?

In the past ten years, a vast array of technologies and services have been developed to help musicians create, promote, distribute and sell their music. Many music observers are quick to categorize these technological developments as a good thing for musicians, especially when compared with the music industry of yore, with its bottlenecks and gatekeepers. While it’s fair to say that musicians’ access to the marketplace has greatly improved, there is a question that lingers; how have these changes impacted musicians’ ability to generate revenue based on their creative work?

In 2010, the nonprofit advocacy organization Future of Music Coalition launched the Artist Revenue Streams project to assess whether and how musicians’ revenue streams are changing in this new music landscape.

Over the past two years, we have collected data directly from individual artists through three methods: (1) in-person interviews with over 80 US-based musicians, composers and managers; (2) financial case studies that dive deep into the accounting and bookkeeping of a handful of full-time performers; and (3) a widely distributed online survey completed by over 5,300 musicians. The full study is available at http://money.futureofmusic.org.

The results are compelling. The earned income from music of the 5,300 survey respondents was $34,455 in aggregate. Live performance was the biggest slice of this collective revenue pie, accounting for 28 percent of the survey populations’ income in the past year. Other significant revenue streams included teaching (22% of aggregated income), being a salaried player in an orchestra or ensemble (19%), session work (11%), income from sound recordings (6%), income from compositions (6%) and merchandising/branding (2%).

We have resisted publishing this collective, top-level revenue pie because of something else that we discovered, especially through the interviews and financial case studies – the American music creator community is large, diverse and specialized. Because of this, a single pie to describe US-based musician income would be misleading. How a salaried player in an orchestra is compensated is vastly different than how an indie rock band makes money, which is different than how a composer who writes bumpers for film and TV makes money. All are musicians, but the revenue streams on which they rely are largely determined by copyright law and business practice, which has historically treated compositions, sound recordings and public performance as distinct streams, even in the cases where one individual plays all three roles simultaneously.

The Artist Revenue Streams project was designed to collect data from musicians playing any or all of these roles, because we see all of them as valid and important parts of the music ecosystem. Instead of lumping the aggregated data together into one set of findings, we have isolated certain populations for apples-to-apples assessments. For instance, we’ve released research memos that look at musicians working in specific genres like jazz. We’ve explained musicians’ relationships with technology. We’ve looked at whether radio airplay matters, and to whom. And, we’ve examined the changes in particular revenue streams, such as income from sound recordings. All of these reports are available online.

Back to our original question: has technology leveled the playing field to a point that musicians can do it all themselves? And an even more critical question, should they try to do it themselves? What are the net effects of teammates and partnerships on musicians’ earning capacity? This article examines data collected through the Artist Revenue Streams project to better understand the impact – and tradeoffs – associated with musicians, income and teammates.

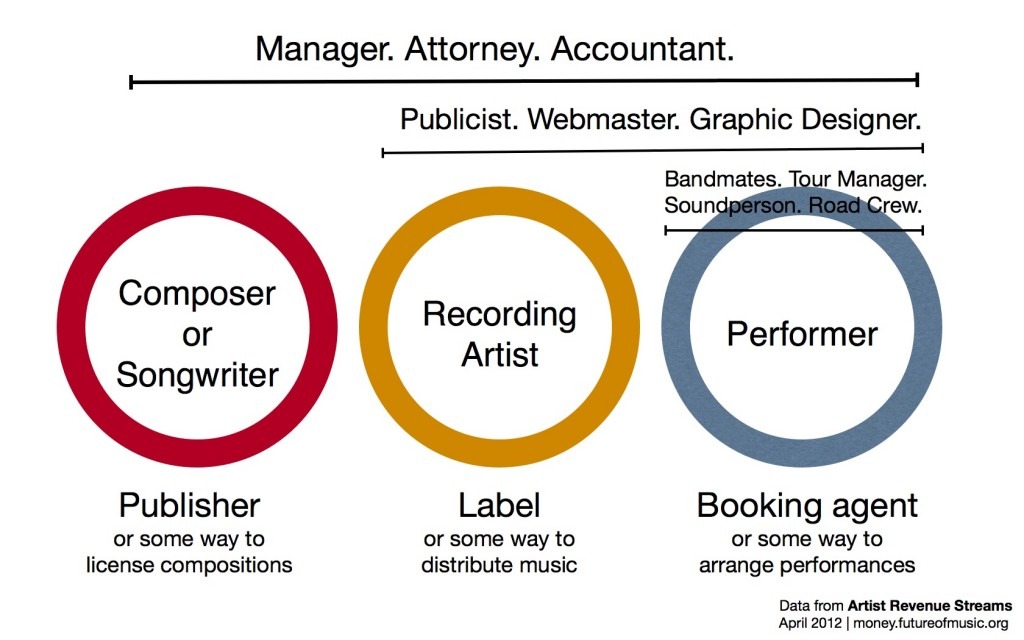

Before we get to the data from the survey, we need to review the three most common teammates – publishers, record labels and booking agents – and whether musicians can take on these roles themselves.

Composers and publishers

Composers and songwriters write music, and they want their compositions to be licensed for use. This means they need to make connections with recording artists, record labels, movie producers, TV shows, and other places that might want to record or license their works. This is frequently done via a publisher, who shops the songs around to performers, record labels and music supervisors, and – for certain composers – also publishes physical sheet music. Publishers also deal with license negotiations, paperwork and payment. And for this work, publishing companies get a percentage (usually 50%) of any licensing deal.

Can composers self-publish? Absolutely. Many songwriters or composers choose to retain control over their publishing. But there are some challenges.

First, a self-published artist will likely never have the same leverage, connections or expertise that an experienced publisher can offer. And second, there is an administrative burden. Someone has to be the designated point person for composition-related requests. If a cable TV show wants to use your music, they’ll need to contact you. If you are relaxed dealing with requests and various negotiations, then self-publishing can work. And, if you self-publish, you get to keep 100% of any income earned by your compositions.

Recording artists

When musicians go in the studio and record either their own songs, or covers of songs that others have written, they end up with a sound recording; songs affixed to tape or hard drive. Traditionally, it has been the job of a record label to take the sound recording and manufacture the commercial product, whether it’s vinyl or 8-tracks or CDs, then distribute it to retailers. For this service, the record label keeps a hefty chunk of wholesale price, and a percentage – usually 50% – of any deals when the sound recording is licensed.

But that’s not all that record labels do. In many instances, labels are also a source of up front cash. They write checks so that artists can go into nice studios and hire good producers. Labels also give recording artists access to producers, to booking agents, and publicists. They also have a staff that can deal with all the boring stuff like accounting, or sending out promotional mailings. The major labels, especially, also have PR muscle. They can get music played on commercial radio. They can get reviews in big magazines. If you’re label-less, getting airplay on commercial radio is virtually impossible.

Record labels also give artists some legitimacy. A label deal means that you’ve piqued the interest enough at a label for them to invest in you. This is a green flag for many other things in the music industry. It makes it a lot easier to get a good booking agent, who can then get you bigger show payments or guarantees. It can get you on bigger tours. It can get you more prominent management. So, a record label deal can impact a recording artist’s income directly and indirectly.

That said, there are some significant tradeoffs to signing a record label deal. In almost all instances, signing a major label contract means that you transfer your sound recording copyrights to the record label for a long, long time.

Second, the label might give you an advance – an upfront payment for signing with them – but it is very difficult to recoup against costs. While you may receive mechanical royalties if you are also the composer, it’s unlikely you will see royalty checks for the sale of your sound recordings in the future. And, history is littered with stories (and legal briefs) about unscrupulous label accounting behavior.

Third, signing a label deal means you are no longer the sole decider about the timing and arc of your career. There’s no “I” in this team.

Self-releasing sound recordings

Can musicians self-release their records? Again, absolutely. It happens all the time and, indeed, services like CD Baby and Tunecore make it easier than ever to enter the digital marketplace.

But the compromise for retaining control is that you have a lot of work to do. Someone is going to have to deal with manufacturing, promotion, and distribution. This might be a team of folks, or it might be the band itself.

And, someone has to pay for all of this. There are a lot of options – more today than in the past – but each of these also involves some work, and some risk; fan funding via sites like Kickstarter or Pledge Music, profit sharing models with indie labels, sponsorship, personal investment, credit cards, or asking family and friends to support the work.

Performers and booking shows

For performers to make money, they need to connect with the right venues and festivals to play. It sounds easy, but if anyone has tried to book a show before – let alone arrange a string of shows into a tour – you know how complicated it can be. So usually, performers and bands hire a booking agent, who negotiates all the details and guarantees with the venue or promoter. If the band is going out on tour, agents can arrange a series of shows, hopefully in some reasonable order. And for their work, booking agents get ten to fifteen percent of tour grosses.

Can musicians book their own shows? Again, yes. The two biggest challenges: it takes a lot of time and perseverance, and calls and emails to promoters during their office hours. Plus, very few bands have the same amount of leverage that a good booking agent has. It’s very likely you won’t get paid as much, and you have nobody to defend you or troubleshoot if things get weird. But, book your own shows, keep 100% of the profits.

The front office

So we’ve quickly described three common team members – publishers, record labels and booking agents. But there are other top-level teammates that creators often need or have, whether they are a composer, recording artist or performer:

And if you’re on tour a lot, you might also need a tour manager, sound person and/or road crew. And, if you’re touring reaches a certain level, you might also need a lighting director, and/or a bus driver.

All of these teammates are optional, and every musician needs to assess the net value of working with them. For some musicians, a manager is crucial. For others, self-managing is the way to go. The important part is understanding the roles that each play, and assessing whether they will improve your situation, whether that means giving you more capacity, making you more money, introducing you to the right people, or doing the tasks that you don’t like to do.

The Team Approach

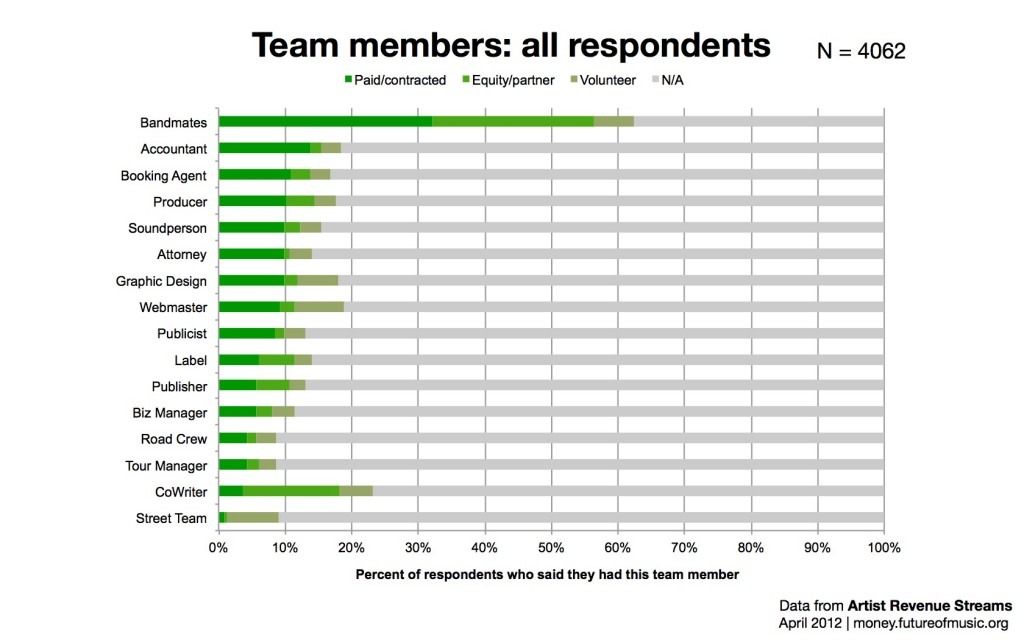

Among many questions on last fall’s Money from Music survey, we asked musicians and composers about who was on their “team”, and about the relationship – whether it was a paid/contracted relationship, a partnership or equity deal, or whether the work was pro bono or volunteer. (See http://money.futureofmusic.org/teams/3/ for more details on the charts below.)

For the 4,062 survey respondents who answered this question, bandmates is at top of list. The list then goes on to accountant, booking agent, and producer. But there are two other things to take away from this chart.

First, there are a lot of possible teammates and, second, there are a great number of working musicians for whom most teammates are simply not applicable, either because they are not a necessary part of their career structure, or that there is a bigger institutional body that takes care of various tasks. This could include orchestral performers who are on salary, for whom roles like a publisher or a street team are not applicable, or session musicians who are hired to perform in the studio or on the road, for whom a booking agent is unnecessary. The “not applicable” answers serve as a reminder of the scope of the US-based music landscape.

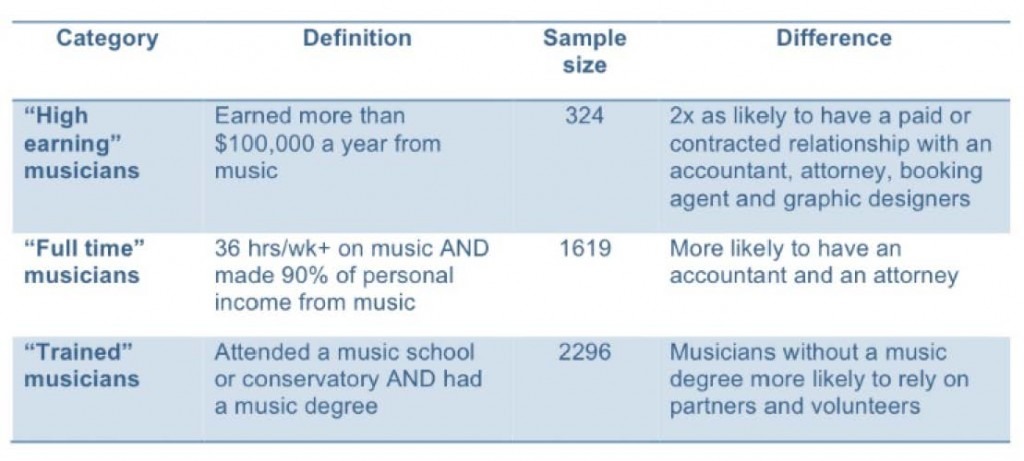

We were also able to filter the data by a number of criteria to see if the teammates changed for different types of musicians.

Asking questions about team members is one thing, but how do these team relationships impact musicians’ earning capacity? In this final section, we will look at how survey respondents’ income was impacted by publishers, record labels and booking agents. (Detailed results can be found at http://money.futureofmusic.org/teams/4/.)

In the aggregate, income derived from compositions accounted for 6% of our survey respondents’ income in the past twelve months (N=5371). But respondents who said they had a paid/contracted relationship with a publisher, were deriving three times as much income from compositions.

The same pattern applied to sound recordings. In the aggregate, income from sound recordings made up about 6% of all respondents’ income (N=5371). But for those with a record label, that percentage more than doubled to 15%.

And, finally, we looked at income from live performance. In the aggregate, this was the biggest slice, accounting for 28% of income for all respondents. But for those who had a booking agent, income from live performances jumped to 43% – an enormous increase.

It’s important that we read this data as correlation, not causation. The data suggests that certain teammates have an impact on musicians’ earning capacity, but they are unlikely to be the sole reason for the differences.

Conclusions

The Artist Revenue Streams project was designed to get a snapshot of musicians’ revenue streams in 2010 and 2011. At the most basic level, we have learned that the majority of US-based musicians and composers rely on a small array of revenue streams, the mix of which is highly dependent on the roles that they play and the genres in which they work. We’ve also learned that technology and the music-related services act as a double-edged sword. Today’s music creators have easy and affordable access to the marketplace and their music fans. But this lowering of barriers has also made the music field more competitive than ever.

Can musicians do it themselves? Probably. There are dozens of technologies and services out there to facilitate it. But the self-made musician’s job title might also include booking agent, publisher, label, graphic designer, merchandiser, accountant, and social media maven.

What about the opposite scenario: should musicians simply farm out all of the non-creative work so they can focus on the music? The data above suggests that some teammates make a difference, either in giving you capacity to do more, or increasing your earnings. But take these findings with a dose of reality — there have been many instances where musicians have been deceived by potential partners, or signed terrible deals. Choosing the right teammates takes research and a full understanding of the risks and benefits. And, even then, there’s no guarantee that good partners will make you successful.

Today’s musicians and composers face new challenges in a landscape with diminishing structural resources and ever-increasing competition. Choosing the appropriate teammates – and designing partnerships that provide a net benefit – is part of this new calculation. The equation will be unique to each musician, but understanding if and how various teammates could have an impact on creative capacity and earnings is an important part of building a successful, sustainable career.

By Kristin Thomson

Kristin Thomson is co-director of Future of Music Coalition’s Artist Revenue Streams project. She is also a musician and co-owner of the indie label Simple Machines Records.

DIY Musicians––Alone Together

One of the music community’s most popular – and romantic – memes is that technology

has leveled the playing field to the point that musicians can “do it

all themselves”. Why sign with a record label when it’s cheap and easy

to get your music on iTunes? Why hire a publicist when you’ve got

Twitter? Who needs a booking agent when you can create a following on

YouTube?

One of the music community’s most popular – and romantic – memes is that technology

has leveled the playing field to the point that musicians can “do it

all themselves”. Why sign with a record label when it’s cheap and easy

to get your music on iTunes? Why hire a publicist when you’ve got

Twitter? Who needs a booking agent when you can create a following on

YouTube?In the past ten years, a vast array of technologies and services have been developed to help musicians create, promote, distribute and sell their music. Many music observers are quick to categorize these technological developments as a good thing for musicians, especially when compared with the music industry of yore, with its bottlenecks and gatekeepers. While it’s fair to say that musicians’ access to the marketplace has greatly improved, there is a question that lingers; how have these changes impacted musicians’ ability to generate revenue based on their creative work?

In 2010, the nonprofit advocacy organization Future of Music Coalition launched the Artist Revenue Streams project to assess whether and how musicians’ revenue streams are changing in this new music landscape.

Over the past two years, we have collected data directly from individual artists through three methods: (1) in-person interviews with over 80 US-based musicians, composers and managers; (2) financial case studies that dive deep into the accounting and bookkeeping of a handful of full-time performers; and (3) a widely distributed online survey completed by over 5,300 musicians. The full study is available at http://money.futureofmusic.org.

The results are compelling. The earned income from music of the 5,300 survey respondents was $34,455 in aggregate. Live performance was the biggest slice of this collective revenue pie, accounting for 28 percent of the survey populations’ income in the past year. Other significant revenue streams included teaching (22% of aggregated income), being a salaried player in an orchestra or ensemble (19%), session work (11%), income from sound recordings (6%), income from compositions (6%) and merchandising/branding (2%).

We have resisted publishing this collective, top-level revenue pie because of something else that we discovered, especially through the interviews and financial case studies – the American music creator community is large, diverse and specialized. Because of this, a single pie to describe US-based musician income would be misleading. How a salaried player in an orchestra is compensated is vastly different than how an indie rock band makes money, which is different than how a composer who writes bumpers for film and TV makes money. All are musicians, but the revenue streams on which they rely are largely determined by copyright law and business practice, which has historically treated compositions, sound recordings and public performance as distinct streams, even in the cases where one individual plays all three roles simultaneously.

The Artist Revenue Streams project was designed to collect data from musicians playing any or all of these roles, because we see all of them as valid and important parts of the music ecosystem. Instead of lumping the aggregated data together into one set of findings, we have isolated certain populations for apples-to-apples assessments. For instance, we’ve released research memos that look at musicians working in specific genres like jazz. We’ve explained musicians’ relationships with technology. We’ve looked at whether radio airplay matters, and to whom. And, we’ve examined the changes in particular revenue streams, such as income from sound recordings. All of these reports are available online.

Back to our original question: has technology leveled the playing field to a point that musicians can do it all themselves? And an even more critical question, should they try to do it themselves? What are the net effects of teammates and partnerships on musicians’ earning capacity? This article examines data collected through the Artist Revenue Streams project to better understand the impact – and tradeoffs – associated with musicians, income and teammates.

Before we get to the data from the survey, we need to review the three most common teammates – publishers, record labels and booking agents – and whether musicians can take on these roles themselves.

Composers and publishers

Composers and songwriters write music, and they want their compositions to be licensed for use. This means they need to make connections with recording artists, record labels, movie producers, TV shows, and other places that might want to record or license their works. This is frequently done via a publisher, who shops the songs around to performers, record labels and music supervisors, and – for certain composers – also publishes physical sheet music. Publishers also deal with license negotiations, paperwork and payment. And for this work, publishing companies get a percentage (usually 50%) of any licensing deal.

Can composers self-publish? Absolutely. Many songwriters or composers choose to retain control over their publishing. But there are some challenges.

First, a self-published artist will likely never have the same leverage, connections or expertise that an experienced publisher can offer. And second, there is an administrative burden. Someone has to be the designated point person for composition-related requests. If a cable TV show wants to use your music, they’ll need to contact you. If you are relaxed dealing with requests and various negotiations, then self-publishing can work. And, if you self-publish, you get to keep 100% of any income earned by your compositions.

Recording artists

When musicians go in the studio and record either their own songs, or covers of songs that others have written, they end up with a sound recording; songs affixed to tape or hard drive. Traditionally, it has been the job of a record label to take the sound recording and manufacture the commercial product, whether it’s vinyl or 8-tracks or CDs, then distribute it to retailers. For this service, the record label keeps a hefty chunk of wholesale price, and a percentage – usually 50% – of any deals when the sound recording is licensed.

But that’s not all that record labels do. In many instances, labels are also a source of up front cash. They write checks so that artists can go into nice studios and hire good producers. Labels also give recording artists access to producers, to booking agents, and publicists. They also have a staff that can deal with all the boring stuff like accounting, or sending out promotional mailings. The major labels, especially, also have PR muscle. They can get music played on commercial radio. They can get reviews in big magazines. If you’re label-less, getting airplay on commercial radio is virtually impossible.

Record labels also give artists some legitimacy. A label deal means that you’ve piqued the interest enough at a label for them to invest in you. This is a green flag for many other things in the music industry. It makes it a lot easier to get a good booking agent, who can then get you bigger show payments or guarantees. It can get you on bigger tours. It can get you more prominent management. So, a record label deal can impact a recording artist’s income directly and indirectly.

That said, there are some significant tradeoffs to signing a record label deal. In almost all instances, signing a major label contract means that you transfer your sound recording copyrights to the record label for a long, long time.

Second, the label might give you an advance – an upfront payment for signing with them – but it is very difficult to recoup against costs. While you may receive mechanical royalties if you are also the composer, it’s unlikely you will see royalty checks for the sale of your sound recordings in the future. And, history is littered with stories (and legal briefs) about unscrupulous label accounting behavior.

Third, signing a label deal means you are no longer the sole decider about the timing and arc of your career. There’s no “I” in this team.

Self-releasing sound recordings

Can musicians self-release their records? Again, absolutely. It happens all the time and, indeed, services like CD Baby and Tunecore make it easier than ever to enter the digital marketplace.

But the compromise for retaining control is that you have a lot of work to do. Someone is going to have to deal with manufacturing, promotion, and distribution. This might be a team of folks, or it might be the band itself.

And, someone has to pay for all of this. There are a lot of options – more today than in the past – but each of these also involves some work, and some risk; fan funding via sites like Kickstarter or Pledge Music, profit sharing models with indie labels, sponsorship, personal investment, credit cards, or asking family and friends to support the work.

Performers and booking shows

For performers to make money, they need to connect with the right venues and festivals to play. It sounds easy, but if anyone has tried to book a show before – let alone arrange a string of shows into a tour – you know how complicated it can be. So usually, performers and bands hire a booking agent, who negotiates all the details and guarantees with the venue or promoter. If the band is going out on tour, agents can arrange a series of shows, hopefully in some reasonable order. And for their work, booking agents get ten to fifteen percent of tour grosses.

Can musicians book their own shows? Again, yes. The two biggest challenges: it takes a lot of time and perseverance, and calls and emails to promoters during their office hours. Plus, very few bands have the same amount of leverage that a good booking agent has. It’s very likely you won’t get paid as much, and you have nobody to defend you or troubleshoot if things get weird. But, book your own shows, keep 100% of the profits.

The front office

So we’ve quickly described three common team members – publishers, record labels and booking agents. But there are other top-level teammates that creators often need or have, whether they are a composer, recording artist or performer:

- A manager, who plays traffic cop on ALL of the other elements

- An attorney, to review contacts

- An account, to deal with compensation and taxes

And if you’re on tour a lot, you might also need a tour manager, sound person and/or road crew. And, if you’re touring reaches a certain level, you might also need a lighting director, and/or a bus driver.

All of these teammates are optional, and every musician needs to assess the net value of working with them. For some musicians, a manager is crucial. For others, self-managing is the way to go. The important part is understanding the roles that each play, and assessing whether they will improve your situation, whether that means giving you more capacity, making you more money, introducing you to the right people, or doing the tasks that you don’t like to do.

The Team Approach

Among many questions on last fall’s Money from Music survey, we asked musicians and composers about who was on their “team”, and about the relationship – whether it was a paid/contracted relationship, a partnership or equity deal, or whether the work was pro bono or volunteer. (See http://money.futureofmusic.org/teams/3/ for more details on the charts below.)

For the 4,062 survey respondents who answered this question, bandmates is at top of list. The list then goes on to accountant, booking agent, and producer. But there are two other things to take away from this chart.

First, there are a lot of possible teammates and, second, there are a great number of working musicians for whom most teammates are simply not applicable, either because they are not a necessary part of their career structure, or that there is a bigger institutional body that takes care of various tasks. This could include orchestral performers who are on salary, for whom roles like a publisher or a street team are not applicable, or session musicians who are hired to perform in the studio or on the road, for whom a booking agent is unnecessary. The “not applicable” answers serve as a reminder of the scope of the US-based music landscape.

We were also able to filter the data by a number of criteria to see if the teammates changed for different types of musicians.

Overall, the survey data suggests that

certain musician types are more likely to have specific team members.

Younger artists rely more on volunteer support, as well as connections

to income from performances. High earners are twice as likely to have a

paid or contracted relationship with an accountant, attorney, booking

agent and graphic designers as their musical peers who earn less. Full

time musicians are more likely to have an accountant or an attorney.

This could be a chicken and egg scenario: does the attorney make it

possible for full time musicians to earn more money, or do they hire the

attorney because they earn more money? The data cannot tell

the difference, but the associations between various musician types and

teammates are interesting, nonetheless.

Teammates’ impact on earningsAsking questions about team members is one thing, but how do these team relationships impact musicians’ earning capacity? In this final section, we will look at how survey respondents’ income was impacted by publishers, record labels and booking agents. (Detailed results can be found at http://money.futureofmusic.org/teams/4/.)

In the aggregate, income derived from compositions accounted for 6% of our survey respondents’ income in the past twelve months (N=5371). But respondents who said they had a paid/contracted relationship with a publisher, were deriving three times as much income from compositions.

The same pattern applied to sound recordings. In the aggregate, income from sound recordings made up about 6% of all respondents’ income (N=5371). But for those with a record label, that percentage more than doubled to 15%.

And, finally, we looked at income from live performance. In the aggregate, this was the biggest slice, accounting for 28% of income for all respondents. But for those who had a booking agent, income from live performances jumped to 43% – an enormous increase.

It’s important that we read this data as correlation, not causation. The data suggests that certain teammates have an impact on musicians’ earning capacity, but they are unlikely to be the sole reason for the differences.

Conclusions

The Artist Revenue Streams project was designed to get a snapshot of musicians’ revenue streams in 2010 and 2011. At the most basic level, we have learned that the majority of US-based musicians and composers rely on a small array of revenue streams, the mix of which is highly dependent on the roles that they play and the genres in which they work. We’ve also learned that technology and the music-related services act as a double-edged sword. Today’s music creators have easy and affordable access to the marketplace and their music fans. But this lowering of barriers has also made the music field more competitive than ever.

Can musicians do it themselves? Probably. There are dozens of technologies and services out there to facilitate it. But the self-made musician’s job title might also include booking agent, publisher, label, graphic designer, merchandiser, accountant, and social media maven.

What about the opposite scenario: should musicians simply farm out all of the non-creative work so they can focus on the music? The data above suggests that some teammates make a difference, either in giving you capacity to do more, or increasing your earnings. But take these findings with a dose of reality — there have been many instances where musicians have been deceived by potential partners, or signed terrible deals. Choosing the right teammates takes research and a full understanding of the risks and benefits. And, even then, there’s no guarantee that good partners will make you successful.

Today’s musicians and composers face new challenges in a landscape with diminishing structural resources and ever-increasing competition. Choosing the appropriate teammates – and designing partnerships that provide a net benefit – is part of this new calculation. The equation will be unique to each musician, but understanding if and how various teammates could have an impact on creative capacity and earnings is an important part of building a successful, sustainable career.

By Kristin Thomson

Kristin Thomson is co-director of Future of Music Coalition’s Artist Revenue Streams project. She is also a musician and co-owner of the indie label Simple Machines Records.

No comments:

Post a Comment