The Cold War nuke that fried satellites

A

secret 50-year-old memo to the British prime minister solved this Cold

War mystery. But could a similar event happen again today?

By Richard Hollingham11 September 2015

On 10 September 1962 an extraordinary memo passed across the desk of British prime minister Harold Macmillan. The confidential document detailed the events leading up to the failure of the UK’s first satellite, Ariel-1.

This spacecraft – a joint venture with the United States – had been launched in April that year to investigate the Earth’s upper atmosphere and study the effects of X-ray radiation from the Sun. This scientific satellite had performed faultlessly until transmissions ceased suddenly on 13 July.

The date of Ariel-1’s demise was no coincidence.

Lord Hailsham wrote of Ariel-1's fate in florid prose to the prime minister of the time, Harold Macmillan (Credit: Getty Images)

The satellite failed four days after the US detonated a 1.4 megaton nuclear warhead, in an experiment known as Starfish Prime, high in the atmosphere 400 kilometres (250 miles) above the Pacific Ocean.

The explosion – the world’s most powerful high altitude nuclear test – created an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) strong enough to disrupt global radio communications and even blow out streetlights on the ground in Hawaii. It also created a new (temporary) radiation belt around the Earth and it was this that did for Ariel-1.

‘Although badly wounded in his solar paddles,’ wrote Hailsham to the PM, ‘he is not quite dead’

British government documents detailing the fate of the satellite remained locked away for 50 years. Reading through a copy of the file stamped ‘secret’ in red letters today, it is clear why: Nasa realised almost immediately what had happened to the satellite but the UK was, embarrassingly, kept in the dark.

When British officials finally pieced together the full story, it fell to science minister, Lord Hailsham, to write to the Prime Minister. His 1962 memo – typed over two pages – relates the saga in some of the most florid, and appropriately Shakespearean language, to ever grace a government document.

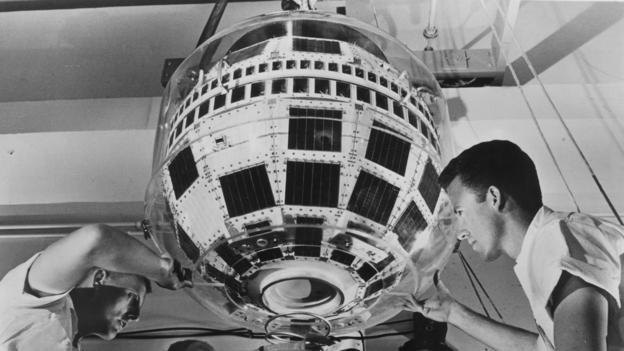

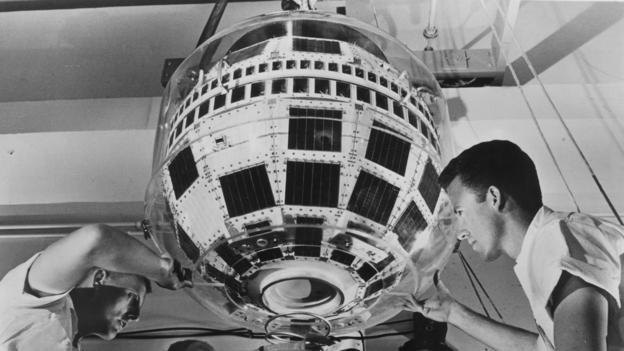

Starfish Prime is also thought to have knocked out the pioneering Telstar communications satellite (Credit: Getty Images)

“Although badly wounded in his solar paddles,” wrote Hailsham to the PM, “he is not quite dead.”

“He still utters intermittently – sometimes intelligibly,” continued the minister. “He may still improve sufficiently to tell us something of value, though he can hardly say ‘merrily shall I live now’.”

Hailsham’s memo suggests that the UK’s financial loss from the project was relatively small compared to the US, who put up the bulk of the cash, and that the wounded satellite had already proved its scientific worth.

“We have got a great deal out of him during his life (short, but neither nasty nor brutish),” said Hailsham. “Before his accident he had transmitted for approximately a thousand hours, and it will take at least a year to analyse the significance of what he has said.”

Military use?

Ariel-1 was not the only satellite badly affected by the Starfish Prime nuclear explosion. The test has also been blamed for the premature failure of the world’s first TV communications satellite, Telstar.

But while Hailsham warned that: “the real moral about their high level explosion is the need for a test ban treaty”, military strategists noted the effects of the weapon with interest.

Could nuclear or EMP weapons, they wondered, be used to knock out spacecraft – disrupting an enemy’s communications, defences or spy satellites or even a nation’s ground-based electrical infrastructure?

“EMP weapons are not a capability that’s widely talked about,” admits Elizabeth Quintana, director of military sciences for the Royal United Services Institute – the respected London-based defence and security think tank. “But they are in current military inventories.”

Designed to be deployed by ground forces or aircraft, EMP weapons systems are capable of either frying all electronic systems in a particular area or targeting specific wavebands – disrupting a nation’s radar defence systems, for instance.

It’s a largely overblown threat – Elizabeth Quintana, Royal United Services Institute

However, aside from fears of collateral damage, one of the big concerns with deploying EMP devices is that the effect is hidden. “When you deliver a bomb it’s quite obvious what damage you’ve done,” says Quintana. “It’s much harder to do that with EMP.”

“While it’s a stealthy way of delivering a temporary effect – such as knocking out enemy air defences as you’re travelling through,” she says, “it may not be effective.”

Radiation shielding

Fears that this EMP technology might also proliferate in space have been much discussed by governments, parliaments and military strategists. But Quintana, who studies developments in weaponry, is not convinced.

“It’s a largely overblown threat,” she contends.

Space is already a hostile enough electromagnetic environment, with satellites and spacecraft being continuously bombarded with cosmic rays and charged particles from the Sun. An EMP weapon – even a repeat of Starfish Prime – Quintana argues, would have little additional effect on modern satellites already hardened against radiation.

“An aggressive solar storm could knock out space infrastructure,” says Quintana. “All space systems that go up today are shielded to some extent from solar radiation.”

Although Starfish Prime destroyed primitive space infrastructure in 1962, there are far more effective, and cheaper, technologies to take out modern satellite systems.

For around $20 for instance you could purchase a GPS jamming device. Illegal or, at best, semi-legal in most countries these locally block the weak signals from navigation satellites. Particularly popular with taxi drivers, allowing them to move anonymously out of sight of controllers, jammers have caused serious problems at airports around the world – inadvertently blocking GPS signals for pilots on final approach.

In 2007, China used a ground-based ballistic missile to destroy a weather satellite

Communications satellites are also relatively easy to jam by directly aiming a radio beam towards them. In recent years BBC Persia TV signals, for instance, have been blocked in this way by Iran.

“Pick a country in the Middle East with conflict or uprising,” says Quintana, “and you will probably find that country would seek to jam commercial satellites in order to prevent opposition messages being broadcast.”

There is even evidence that China has developed a ground based laser system to dazzle spy satellites as they pass overhead.

‘Dragging’ threat

As for taking out spacecraft in orbit, ground-based systems also have the edge. In 2007, China used a ground-based ballistic missile to destroy a weather satellite, creating a dangerous cloud of orbiting space debris and angering the international community.

There is, however, some space-based technology being developed that could be used in future to take-out an enemy’s spacecraft. As it turns out, it is the same technology being developed to remove debris.

“One of the technologies for debris removal is to have satellites capable of dragging old satellites out of orbit,” says Quintana. “Obviously, you could use the same technologies to change the orbit of live satellites.”

Missiles are a more likely military threat to satellites than EMP pulses (Credit: Science Photo Library)

In the same way, it would be possible to fit a spacecraft with a small and directed EMP weapon. “You could launch a satellite into space near another satellite and effectively fry the circuitry,” says Quintana.

Starfish Prime was a terrifying demonstration of the mass-destructive potential of EMP weapons. But the reality is if you are intent on destroying or disrupting space infrastructure today, there are far easier ways to do it. The fact that it is relatively straightforward is of increasing concern to the world’s space nations, given how reliant we are on satellites for our daily lives.

As for Lord Hailsham, a year after his memo, he got the test ban treaty he desired – signed in 1963 by the US, UK and the Soviet Union.

He also received a nice reply from the Prime Minister: “Many thanks for your splendid minute,” the PM wrote… before the file was locked away for 50 years.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150910-the-nuke-that-fried-satellites-with-terrifying-results

NOTE: I HAVE NEVER HAD A MORE DIFFICULT POSTING THAN THIS ARTICLE. HEED IT AND THE GHOST TRAIN WELL. THEY WERE SABOTAGED AT EVERY CORNER FOR SOME REASON.

By Richard Hollingham11 September 2015

On 10 September 1962 an extraordinary memo passed across the desk of British prime minister Harold Macmillan. The confidential document detailed the events leading up to the failure of the UK’s first satellite, Ariel-1.

This spacecraft – a joint venture with the United States – had been launched in April that year to investigate the Earth’s upper atmosphere and study the effects of X-ray radiation from the Sun. This scientific satellite had performed faultlessly until transmissions ceased suddenly on 13 July.

The date of Ariel-1’s demise was no coincidence.

Lord Hailsham wrote of Ariel-1's fate in florid prose to the prime minister of the time, Harold Macmillan (Credit: Getty Images)

The satellite failed four days after the US detonated a 1.4 megaton nuclear warhead, in an experiment known as Starfish Prime, high in the atmosphere 400 kilometres (250 miles) above the Pacific Ocean.

The explosion – the world’s most powerful high altitude nuclear test – created an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) strong enough to disrupt global radio communications and even blow out streetlights on the ground in Hawaii. It also created a new (temporary) radiation belt around the Earth and it was this that did for Ariel-1.

‘Although badly wounded in his solar paddles,’ wrote Hailsham to the PM, ‘he is not quite dead’

British government documents detailing the fate of the satellite remained locked away for 50 years. Reading through a copy of the file stamped ‘secret’ in red letters today, it is clear why: Nasa realised almost immediately what had happened to the satellite but the UK was, embarrassingly, kept in the dark.

When British officials finally pieced together the full story, it fell to science minister, Lord Hailsham, to write to the Prime Minister. His 1962 memo – typed over two pages – relates the saga in some of the most florid, and appropriately Shakespearean language, to ever grace a government document.

Starfish Prime is also thought to have knocked out the pioneering Telstar communications satellite (Credit: Getty Images)

“Although badly wounded in his solar paddles,” wrote Hailsham to the PM, “he is not quite dead.”

“He still utters intermittently – sometimes intelligibly,” continued the minister. “He may still improve sufficiently to tell us something of value, though he can hardly say ‘merrily shall I live now’.”

Hailsham’s memo suggests that the UK’s financial loss from the project was relatively small compared to the US, who put up the bulk of the cash, and that the wounded satellite had already proved its scientific worth.

“We have got a great deal out of him during his life (short, but neither nasty nor brutish),” said Hailsham. “Before his accident he had transmitted for approximately a thousand hours, and it will take at least a year to analyse the significance of what he has said.”

Military use?

Ariel-1 was not the only satellite badly affected by the Starfish Prime nuclear explosion. The test has also been blamed for the premature failure of the world’s first TV communications satellite, Telstar.

But while Hailsham warned that: “the real moral about their high level explosion is the need for a test ban treaty”, military strategists noted the effects of the weapon with interest.

Could nuclear or EMP weapons, they wondered, be used to knock out spacecraft – disrupting an enemy’s communications, defences or spy satellites or even a nation’s ground-based electrical infrastructure?

“EMP weapons are not a capability that’s widely talked about,” admits Elizabeth Quintana, director of military sciences for the Royal United Services Institute – the respected London-based defence and security think tank. “But they are in current military inventories.”

Designed to be deployed by ground forces or aircraft, EMP weapons systems are capable of either frying all electronic systems in a particular area or targeting specific wavebands – disrupting a nation’s radar defence systems, for instance.

It’s a largely overblown threat – Elizabeth Quintana, Royal United Services Institute

However, aside from fears of collateral damage, one of the big concerns with deploying EMP devices is that the effect is hidden. “When you deliver a bomb it’s quite obvious what damage you’ve done,” says Quintana. “It’s much harder to do that with EMP.”

“While it’s a stealthy way of delivering a temporary effect – such as knocking out enemy air defences as you’re travelling through,” she says, “it may not be effective.”

Radiation shielding

Fears that this EMP technology might also proliferate in space have been much discussed by governments, parliaments and military strategists. But Quintana, who studies developments in weaponry, is not convinced.

“It’s a largely overblown threat,” she contends.

Space is already a hostile enough electromagnetic environment, with satellites and spacecraft being continuously bombarded with cosmic rays and charged particles from the Sun. An EMP weapon – even a repeat of Starfish Prime – Quintana argues, would have little additional effect on modern satellites already hardened against radiation.

“An aggressive solar storm could knock out space infrastructure,” says Quintana. “All space systems that go up today are shielded to some extent from solar radiation.”

Although Starfish Prime destroyed primitive space infrastructure in 1962, there are far more effective, and cheaper, technologies to take out modern satellite systems.

For around $20 for instance you could purchase a GPS jamming device. Illegal or, at best, semi-legal in most countries these locally block the weak signals from navigation satellites. Particularly popular with taxi drivers, allowing them to move anonymously out of sight of controllers, jammers have caused serious problems at airports around the world – inadvertently blocking GPS signals for pilots on final approach.

In 2007, China used a ground-based ballistic missile to destroy a weather satellite

Communications satellites are also relatively easy to jam by directly aiming a radio beam towards them. In recent years BBC Persia TV signals, for instance, have been blocked in this way by Iran.

“Pick a country in the Middle East with conflict or uprising,” says Quintana, “and you will probably find that country would seek to jam commercial satellites in order to prevent opposition messages being broadcast.”

There is even evidence that China has developed a ground based laser system to dazzle spy satellites as they pass overhead.

‘Dragging’ threat

As for taking out spacecraft in orbit, ground-based systems also have the edge. In 2007, China used a ground-based ballistic missile to destroy a weather satellite, creating a dangerous cloud of orbiting space debris and angering the international community.

There is, however, some space-based technology being developed that could be used in future to take-out an enemy’s spacecraft. As it turns out, it is the same technology being developed to remove debris.

“One of the technologies for debris removal is to have satellites capable of dragging old satellites out of orbit,” says Quintana. “Obviously, you could use the same technologies to change the orbit of live satellites.”

Missiles are a more likely military threat to satellites than EMP pulses (Credit: Science Photo Library)

In the same way, it would be possible to fit a spacecraft with a small and directed EMP weapon. “You could launch a satellite into space near another satellite and effectively fry the circuitry,” says Quintana.

Starfish Prime was a terrifying demonstration of the mass-destructive potential of EMP weapons. But the reality is if you are intent on destroying or disrupting space infrastructure today, there are far easier ways to do it. The fact that it is relatively straightforward is of increasing concern to the world’s space nations, given how reliant we are on satellites for our daily lives.

As for Lord Hailsham, a year after his memo, he got the test ban treaty he desired – signed in 1963 by the US, UK and the Soviet Union.

He also received a nice reply from the Prime Minister: “Many thanks for your splendid minute,” the PM wrote… before the file was locked away for 50 years.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150910-the-nuke-that-fried-satellites-with-terrifying-results

NOTE: I HAVE NEVER HAD A MORE DIFFICULT POSTING THAN THIS ARTICLE. HEED IT AND THE GHOST TRAIN WELL. THEY WERE SABOTAGED AT EVERY CORNER FOR SOME REASON.