As the secret state continues trawling the electronic

communications of hundreds of millions of Americans, lusting after what

securocrats euphemistically call “actionable intelligence,” a notional

tipping point that transforms a “good” citizen into a “criminal”

suspect, the role played by telecommunications and technology firms

cannot be emphasized enough.

Ever since former NSA contractor Edward Snowden began leaking secrets

to media outlets about government surveillance programs, one fact

stands out: The

zero probability these privacy-killing projects

would be practical without close (and very profitable) “arrangements”

made with phone companies, internet service providers and other

technology giants.

Indeed, a top secret NSA Inspector General’s report published by

The Guardian,

revealed that the agency “maintains relationships with over 100 US

companies,” adding that the US has the “home field advantage as the

primary hub for worldwide telecommunications.”

Similarly, the British fiber optic cable tapping program,

TEMPORA,

referred to telcos and ISPs involved in the spying as “intercept

partners.” The names of the firms were considered so sensitive that GCHQ

“went to great lengths” to keep their identities hidden, fearing

exposure “would cause ‘high-level political fallout’.”

With new privacy threats looming on the horizon, including what

CNET

described as ongoing efforts by the FBI and NSA “to obtain the master

encryption keys that Internet companies use to shield millions of users’

private Web communications from eavesdropping,” along with

new government demands that ISPs and cell phone carriers “divulge users’ stored passwords,” can we trust these firms?

And with

Microsoft

and other tech giants, collaborating closely with “US intelligence

services to allow users’ communications to be intercepted, including

helping the National Security Agency to circumvent the company’s own

encryption,” can we afford to?

Hiding in Plain Sight

Ever since retired union technician Mark Klein blew the lid off

AT&T’s secret surveillance pact with the US government in 2006, we

know user privacy is

not part of that firm’s business model.

The technical source for the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s lawsuit,

Hepting v. AT&T and the author of

Wiring Up the Big Brother Machine,

Klein was the first to publicly expose how NSA was “vacuuming up

everything flowing in the Internet stream: e-mail, web browsing,

Voice-Over-Internet phone calls, pictures, streaming video, you name

it.”

We also know from reporting by

USA Today,

that the agency “has been secretly collecting the phone call records of

tens of millions of Americans” and had amassed “the largest database

ever assembled in the world.”

Three of those data-slurping programs, UPSTREAM, PRISM and

X-KEYSCORE, shunt domestic and global communications collected from

fiber optic cables, the servers of Apple, Google, Microsoft and Yahoo,

along with telephone data (including metadata, call content and

location) grabbed from AT&T, Sprint and Verizon into NSA-controlled

databases.

But however large, a database is only useful to an organization,

whether its a corporation or a spy agency, if the oceans of data

collected can be searched and extracted in meaningful ways.

To the growing list of spooky acronyms and code-named black programs revealed by Edward Snowden, what

other projects, including those in the public domain, are hiding in plain sight?

Add Google’s

BigTable and Yahoo’s

Hadoop

to that list. Both are massive storage and retrieval systems designed

to crunch ultra-large data sets and were developed as a practical means

to overcome “big data” conundrums.

According to the Mountain View behemoth, “BigTable is a distributed

storage system for managing structured data that is designed to scale to

a very large size: petabytes of data across thousands of commodity

servers.” Along with web indexing, Google Earth and Google Finance,

BigTable performs “bulk processing” for “real-time data serving.”

Down the road in Sunnyvale, Yahoo developed Hadoop as “an open source

Java framework for processing and querying vast amounts of data on

large clusters of commodity hardware.” According to Yahoo, Hadoop has

become “the industry

de facto framework for big data

processing.” Like Google’s offering, Hadoop enable applications to work

with thousands of computers and petabytes of data simultaneously.

Prominent corporate clients using these applications include Amazon,

AOL, eBay, Facebook, IBM, Microsoft and Twitter, among many others.

‘Big Data’ Dynamo

Who might

also have a compelling interest in cataloging and

searching through very large data sets, away from prying eyes, and at

granular levels to boot? It should be clear following Snowden’s

disclosures, what’s good for commerce is also a highly-prized commodity

among global eavesdroppers.

Despite benefits for medical and scientific researchers sifting through mountains of data, as

Ars Technica

pointed out BigTable and Hadoop “lacked compartmentalized security”

vital to spy shops, so “in 2008, NSA set out to create a better version

of BigTable, called Accumulo.”

Developed by agency specialists, it was eventually handed off to the

“non-profit” Apache Software Foundation. Touted as an open software

platform,

Accumulo is described in Apache literature as “a robust, scalable, high performance data storage and retrieval system.”

“The platform allows for compartmentalization of segments of big data

storage through an approach called cell-level security. The security

level of each cell within an Accumulo table can be set independently,

hiding it from users who don’t have a need to know: whole sections of

data tables can be hidden from view in such a way that users (and

applications) without clearance would never know they weren’t there,”

Ars Technica explained.

The tech site

Gigaom

noted, Accumulo is the “technological linchpin to everything the NSA is

doing from a data-analysis perspective,” enabling agency analysts to

“generate near real-time reports from specific patterns in data,”

Ars averred.

“For instance, the system could look for specific words or addressees

in e-mail messages that come from a range of IP addresses; or, it could

look for phone numbers that are two degrees of separation from a

target’s phone number. Then it can spit those chosen e-mails or phone

numbers into another database, where NSA workers could peruse it at

their leisure.”

(Since that

Ars piece appeared, we have since learned that NSA is now conducting what is described as “three-hop analysis,” that is,

three degrees of separation

from a target’s email or phone number. This data dragnet “could allow

the government to mine the records of 2.5 million Americans when

investigating one suspected terrorist,” the

Associated Press observed).

“In other words,”

Ars explained, “Accumulo allows the NSA to

do what Google does with your e-mails and Web searches–only with

everything that flows across the Internet, or with every phone call you

make.”

Armed with a “dual-use” program like Accumulo, the dirty business of

assembling a user’s political profile, or shuttling the names of

“suspect” Americans into a national security index, is as now easy as

downloading a song from iTunes!

And it isn’t only Silicon Valley giants cashing-in on the “public-private” spy game.

Just as the

CIA-funded Palantir,

a firm currently valued at $8 billion and exposed two years ago as a

“partner” in a Bank of America-brokered scheme to bring down

WikiLeaks, profited from CIA interest in its social mapping

Graph application, so too, the NSA spin-off

Sqrrl, launched in 2012 with agency blessings, stands to make a killing off software its corporate officers helped develop for NSA.

Co-founded by nine-year agency veteran Adam Fuchs, Sqrrl sells

commercial versions of Accumulo and has partnered-up with Amazon, Dell,

MapR and Northrop Grumman. According to published reports, like other

start-ups with an intelligence angle, Sqrrl is hoping to hook-up with

CIA’s venture capital arm

In-Q-Tel.

Its obvious why the application is of acute interest to American spy shops. Fuchs told

Gigaom that Accumulo operates “at thousands-of-nodes scale” within NSA data centers.

“There are multiple instances each storing tens of petabytes (1

petabyte equals 1,000 terabytes or 1 million gigabytes) of data and it’s

the backend of the agency’s most widely used analytical capabilities.”

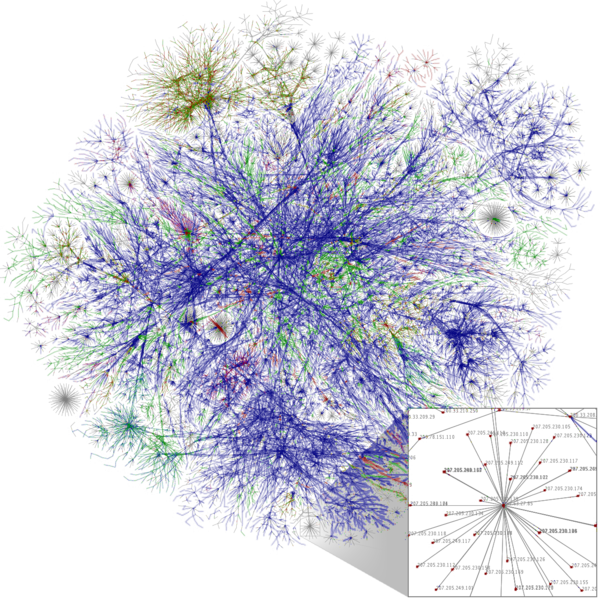

Accumulo’s analytical functions work because of its ability to

perform lightning-quick searches called “graph analysis,” a method for

uncovering unique relationships between people hidden within vast oceans

of data.

According to

Forbes,

“we know that the NSA has successfully tested Accumulo’s graph analysis

capabilities on some huge data sets–in one case on a 1200 node Accumulo

cluster with over a petabyte of data and 70 trillion edges.”

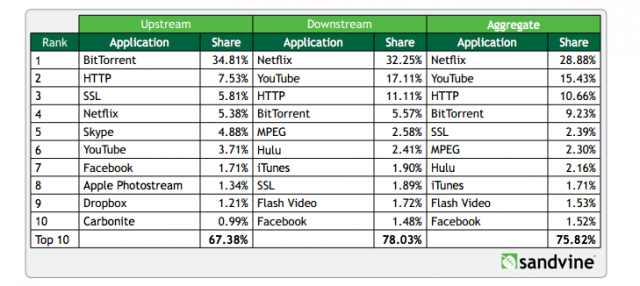

Considering, as

Wired

reported, that “on an average day, Google accounts for about 25 percent

of all consumer internet traffic running through North American ISPs,”

and the Mountain View firm allowed the FBI and NSA to tap directly into

their central servers as

The Washington Post

disclosed, the negative impact on civil rights and political liberties

when systems designed for the Pentagon are monetized, should be evident.

Once fully commercialized, how much more intrusive will employers,

marketing firms, insurance companies or local and state police with

mountains of data only a mouse click away, become?

Global Panopticon

The sheer scope of NSA programs such as UPSTREAM, PRISM or X-KEYSCORE, exposed by the Brazilian daily,

O Globo should give pause.

A crude illustration (at the top of this post), shows that all data

collected in X-KEYSCORE “sessions” are processed in petabyte scale

batches captured from “web-based searches” that can be “retrospectively”

queried to locate and profile a “target.”

This requires enormous processing power; a problem the agency

may have solved with Accumulo or similar applications.

Once collected, data is separated into digestible fragments (phone

numbers, email addresses and log ins), then reassembled at lightning

speeds for searchable queries in graphic form. Information gathered in

the hopper includes not only metadata tables, but the “full log,”

including what spooks call Digital Network Intelligence, i.e., user

content.

And while it may not

yet be practical for NSA to collect and store each single packet flowing through the pipes, the agency is

already

collecting and storing vast reams of data intercepted from our phone

records, IP addresses, emails, web searches and visits, and is doing so

in much the same way that Amazon, eBay, Google and Yahoo does.

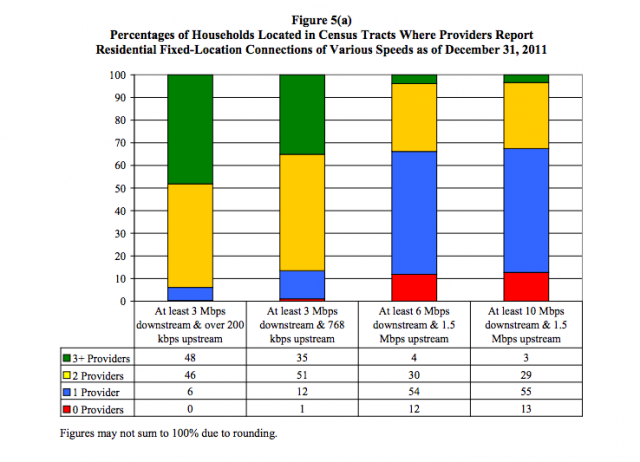

As the volume of global communications increase each year at near

exponential levels, data storage and processing pose distinct problems.

Indeed, Cisco Systems forecast in their 2012

Visual Networking Index

that global IP traffic will grow three-fold over the next five years

and will carry up to 4 exabytes of data per day, for an annual rate of

1.4 zettabytes by 2017.

This does much to explain why NSA is building a $2 billion Utah Data

Center with 22 acres of digital storage space that can hold up to 5

zettabytes of data and expanding already existing centers at Fort

Gordon, Lackland Air Force Base, NSA Hawaii and at the agency’s Fort

Meade headquarters.

Additionally, NSA is feverishly working to bring supercomputers

online “that can execute a quadrillion operations a second” at the

Multiprogram Research facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee where enriched

uranium for nuclear weapons is manufactured, as James Bamford disclosed

last year in

Wired.

As the secret state sinks tens of billions of dollars into various

big data digital programs, and carries out research on next-gen

cyberweapons more destructive than Flame or Stuxnet, as those

supercomputers come online the cost of cracking encrypted passwords and

communications will continue to fall.

Stanford University computer scientist David Mazières told CNET that

mastering encrypted communications would “include an order to extract

them from the server or network when the user logs in–which has been

done before–or installing a keylogger at the client.”

This is

precisely what Microsoft has already done with its

SkyDrive cloud storage service “which now has 250 million users

worldwide” and exabytes of data ready to be pilfered, as

The Guardian disclosed.

One document “stated that NSA already had pre-encryption access to

Outlook email. ‘For Prism collection against Hotmail, Live, and

Outlook.com emails will be unaffected because Prism collects this data

prior to encryption’.”

Call the “wrong” person or click a dodgy link and you might just be

the lucky winner of a one-way trip to indefinite military detention

under

NDAA, or worse.

What should also be clear since revelations about NSA surveillance

programs began spilling out last month, is not a single ruling class

sector in the United States–including corporations, the media, nor any

branch of the US government–has the least interest in defending

democratic rights or rolling-back America’s emerging police state.

that he needs a public handout because “this is a motherfucking tough business, and I’m gonna keep fighting the powers that be.”

that he needs a public handout because “this is a motherfucking tough business, and I’m gonna keep fighting the powers that be.”

purchasing

the land for about $400,000 in 1989, Lee built a four-bedroom home on

the property (which is now worth several million dollars).

purchasing

the land for about $400,000 in 1989, Lee built a four-bedroom home on

the property (which is now worth several million dollars).