Risk Experts Who Predicted 2008 Financial Crash Believe GMOs To Be Riskier Than 2008 Crash

“The G.M.O. Experiment, Carried Out In Real Time

and with Our Entire Food and Ecological System As Its Laboratory, Is

Perhaps the Greatest Case of Human Hubris Ever”

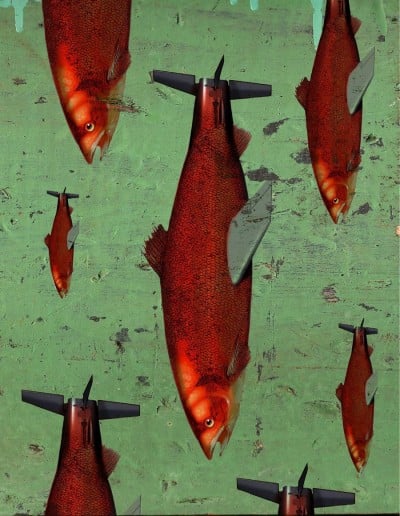

Image: Painting by Anthony Freda: www.AnthonyFreda.com

Risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb predicted the 2008

financial crisis, by pointing out that commonly-used risk models were

wrong. Taleb – a distinguished professor of risk engineering at New

York University, and author of best-sellers The Black Swan and Fooled by

Randomness – Taleb became financially independent after the crash of

1987, and wealthy during the 2008 financial crisis.

Taleb noted last year that most boosters for genetically modified foods (GMOs) – including scientists – are totally ignorant about risk analysis. Taleb said that proliferating GMOs could lead to “an irreversible termination of life [on] the planet.”

This month, Taleb – and tail-hedging expert Mark Spitznagel, who

also made a hugely profitable billion dollar derivatives bet on the

stock market crash of 2008 – wrote in the New York Times:

Before

the crisis that started in 2007, both of us believed that the financial

system was fragile and unsustainable, contrary to the near ubiquitous

analyses at the time.

Now, there is something vastly riskier facing us, with risks that entail the survival of the global ecosystem

— not the financial system. This time, the fight is against the current

promotion of genetically modified organisms, or G.M.O.s.

Our critics held that

the financial system was improved thanks to the unwavering progress of

science and technology, which had blessed finance with more

sophisticated economic insight. But the “tail risks,” or the effect from

rare but monstrously consequential events, we held, had been

increasing, owing to increasing complexity and globalization. Given that

almost nobody was paying attention to the risks, we

set ourselves and our clients to be protected from an eventual collapse

of the banking system, which subsequently happened to the benefit of

those who were prepared.

***

We

were repeatedly told that there was evidence that the system was

stable, that we were in “the Great Moderation,” a common practice that

mistakes absence of evidence for evidence of absence. For the financial

system to be viable, the solution is for it to resemble the restaurant

business: decentralized, with mistakes that stay local and that cannot

bring down the entire apparatus.

Indeed, a Nobel prize-winning economist and many other experts say that too much centralization destabilizes economies and other systems.

Taleb and Spitznagel by pointing out that the GMO-cheerleaders are

making the same anti-scientific arguments as those who said the

financial system was stable prior to 2008:

The

financial system nearly collapsed, but it was only money. We now find

ourselves facing nearly the same five fallacies for our caution against

the growth in popularity of G.M.O.s. [Nearly 80% of all food produced in the U.S. contains GMOs.]

First, there has been a

tendency to label anyone who dislikes G.M.O.s as anti-science — and put

them in the anti-antibiotics, antivaccine, even Luddite category. There

is, of course, nothing scientific about the comparison. Nor is the

scholastic invocation of a “consensus” a valid scientific argument.

Interestingly,

there are similarities between arguments that are pro-G.M.O. and snake

oil, the latter having relied on a cosmetic definition of science. The

charge of “therapeutic nihilism” was leveled at people who contested

snake oil medicine at the turn of the 20th century. (At that time,

anything with the appearance of sophistication was considered

“progress.”)

Second, we are told

that a modified tomato is not different from a naturally occurring

tomato. That is wrong: The statistical mechanism by which a tomato was

built by nature is bottom-up, by tinkering in small steps (as with the

restaurant business, distinct from contagion-prone banks). In nature,

errors stay confined and, critically, isolated.

Third, the

technological salvation argument we faced in finance is also present

with G.M.O.s, which are intended to “save children by providing them

with vitamin-enriched rice.” The argument’s flaw is obvious: In a

complex system, we do not know the causal chain, and it is better to

solve a problem by the simplest method, and one that is unlikely to

cause a bigger problem.

Fourth, by leading to

monoculture — which is the same in finance, where all risks became

systemic — G.M.O.s threaten more than they can potentially help.

Ireland’s population was decimated by the effect of monoculture during

the potato famine. Just consider that the same can happen at a planetary

scale.

We noted in 2009:

It has been accepted science for decades that when all

the farmers in a certain region grow the same strain of the same crop –

called “monoculture” – the crops become much more susceptible.

Why?

Because any bug (insect or germ) which happens to like that particular strain could take out the whole crop on pretty much all of the region’s farms.

For example, one type of grasshopper – called “differential

grasshoppers” – loves corn. If everyone grows the same strain of corn in

a town in the midwest, and differential grasshoppers are anywhere

nearby, they may come and wipe out the entire town’s crops (that’s why

monoculture crops require such high levels of pesticides).

On the other hand, if farmers grow a lot of different types of crops

(“polyculture”) , then a pest might get some crops, but the rest will

survive.

Taleb and Spitznagel conclude:

The G.M.O. experiment, carried out in real time and with our entire food and ecological system as its laboratory, is perhaps the greatest case of human hubris ever. It creates yet another systemic, “too big too fail” enterprise — but one for which no bailouts will be possible when it fails.

In the real world –

using statistical analysis – GMOs are inferior when compared to other

types of food, because GMOs are associated with: