http://www.wired.com/opinion/2013/01/wiretap-backdoors/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+wired%2Findex+%28Wired%3A+Top+Stories%29

The FBI Needs Hackers, Not Backdoors

Just imagine if all the applications and services you saw or heard about

at CES

last week had to be designed to be “wiretap ready” before they could be

offered on the market. Before regular people like you or me could use

them.

Yet that’s a real possibility. For the last few years, the FBI’s

been warning

that its surveillance capabilities are “going dark,” because internet

communications technologies — including devices that connect to the

internet — are getting too difficult to intercept with current law

enforcement tools. So the FBI wants a more wiretap-friendly internet,

and legislation to mandate it will likely be proposed this year.

But a better way to protect privacy and security on the internet may be for the FBI

to get better at breaking into computers.

Whoa, what? Let us explain.

Whether we like them or not, wiretaps — legally authorized ones only,

of course — are an important law enforcement tool. But mandatory

wiretap backdoors in internet services would invite at least as much new

crime as it could help solve.

Especially because we’re knee deep in what can only be called a

cybersecurity crisis. Criminals, rival nation states, and rogue hackers

routinely seek out and exploit vulnerabilities in our computers and

networks — much faster than we can fix them. In this cybersecurity

landscape, wiretapping interfaces are particularly juicy targets.

Every connection, every interface increases our exposure and makes criminals’ jobs easier.

Matt Blaze

directs the Distributed Systems Lab at the University of Pennsylvania,

where he studies cryptography and secure systems. Prior to joining Penn,

he was a distinguished member of technical staff at AT&T Bell

Labs. He can be found on Twitter at mattblaze.

Susan Landau is currently a Guggenheim Scholar. She was a distinguished engineer at Sun Microsystems. Landau is the author of Surveillance or Security? The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies.

We’ve Been Here Before

Two decades ago, the FBI complained it was having trouble tapping the

then-latest cellphones and digital telephone switches. After extensive

FBI lobbying, Congress passed the Communications Assistance for Law

Enforcement Act (CALEA) in 1994, mandating that

all telephone switches include FBI-approved wiretapping capabilities.

CALEA was justifiably controversial, not least because its

requirement for “backdoors” across our communications infrastructure

seemed like a security nightmare: How could we keep criminals and

foreign spies from exploiting weaknesses in the new wiretapping

features? Would we even be able to detect them when they did?

Those fears were soon borne out. In 2004, a mysterious someone — the case was never solved —

hacked the wiretap backdoors of a Greek cellular switch to listen in on senior government officials … including the prime minister.

Think this could only happen abroad? Some years ago, the U.S. National Security Agency

discovered

that every telephone switch for sale to the Department of Defense had

security vulnerabilities in their mandated wiretap implementations.

Every. Single. One.

Given these risks, you might think now’s a good time to

scale back CALEA and harden our communications infrastructure against attack.

But the FBI wants to do the opposite. They want to massively expand

the wiretap mandate beyond phone services to internet-based services:

instant messaging systems, video conferencing, e-mail, smartphone apps,

and so on.

Yet on the internet, the threats — and consequences of compromise —

are even more serious than with telephone switches. Not only would

wiretap mandates put a damper on innovation, but the FBI is effectively

choosing making it easier to solve some crimes by opening the door to

other crimes.

Are these really the only options we have? No.

The FBI wants to massively expand the wiretap mandate beyond phone services to internet-based services.

Bugs Are Backdoors, Too

If it turns out that important surveillance sources really are going

dark — and that’s a big if (it’s not only on TV that modern tech already

makes it easier to surveil suspects) — there’s no need to mandate wiretap backdoors.

That’s because there’s already an alternative in place: buggy, vulnerable software.

The same vulnerabilities that enable crime in the first place also

give law enforcement a way to wiretap — when they have a narrowly

targeted warrant and can’t get what they’re after some other way. The

very reasons why we have Patch Tuesday followed by Exploit Wednesday,

why opening e-mail attachments feels like Russian roulette, and why

anti-virus software and firewalls aren’t enough to keep us safe online

provide the very backdoors the FBI wants.

Since the beginning of software time, every technology device — and

especially ones that use the internet — has and continues to have

vulnerabilities. The sad truth is that as hard as we may try, as often

as we patch what we can patch, no one knows how to build secure software

for the real world.

Instead of building special (and more vulnerable) new wiretapping

interfaces, law enforcement can tap their targets’ devices and apps

directly by exploiting existing vulnerabilities. Instead of changing the

law, they can use specialized, narrowly targeted exploit tools to do

the tapping.

In fact, targeted FBI computer exploits are nothing new. When the FBI

placed a “keylogger” on suspected bookmaker Nicky Scarfo Jr.’s computer

in 2000, it allowed the government to win a conviction from decrypting

his files after gaining access to his PGP password. A few years later,

the FBI developed “CIPAV,”

a piece of software that enables investigators to download such spying tools electronically.

The sad truth is that no one knows how to build secure software for the real world.

Exploits aren’t a magic wiretapping bullet. There’s engineering

effort involved in finding vulnerabilities and building exploit tools,

and that costs money.

And when the FBI finds a vulnerability in a major piece of software,

shouldn’t they let the manufacturer know so innocent users can

patch? Should the government buy exploit tools on the underground market

or build them themselves? These are difficult questions, but they’re

not fundamentally different from those we grapple with for dealing with

informants, weapons, and other potentially dangerous law enforcement

tools.

But at least targeted exploit tools are harder to abuse on a large scale than globally mandated backdoors in

every switch,

every router,

every application,

every device.

While the thought of the FBI exploiting vulnerabilities to conduct

authorized wiretaps makes us a bit queasy, at least that approach leaves

the infrastructure, and everyone else’s devices, alone.

Ultimately, not much is gained — but too much is lost — by mandating

special “lawful intercept” interfaces in internet systems. There’s no

need to talk about adding deliberate backdoors until we figure out how

to get rid of the unintentional ones … and that won’t be for a long,

long time.

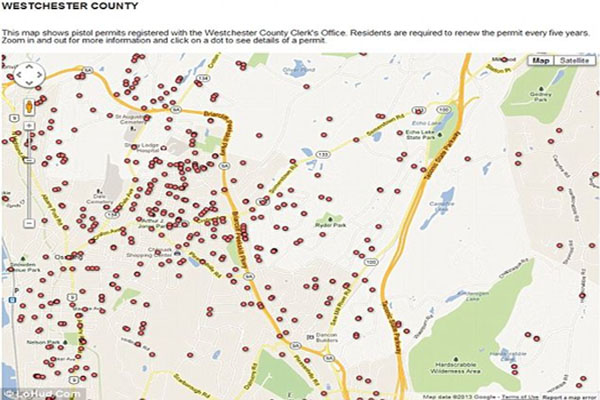

Deliberately targeted? This home is White Plains, New York,

Deliberately targeted? This home is White Plains, New York,  ‘No comment’: The homeowner told News12 he had nothing to add while police continued investigations into the burglary

‘No comment’: The homeowner told News12 he had nothing to add while police continued investigations into the burglary

‘Reckless’: A New York State Senator blasted the Journal News for their controversial gun map

‘Reckless’: A New York State Senator blasted the Journal News for their controversial gun map

Calling

for change: The paper said that they produced the map because in the

wake of the Newtown shooting many people wanted to know who had legal

guns in their neighborhood, and there were protests across the country

(pictured).

Calling

for change: The paper said that they produced the map because in the

wake of the Newtown shooting many people wanted to know who had legal

guns in their neighborhood, and there were protests across the country

(pictured).

On the list: As well as Journal News the website Gawker published a 446-page list of licensed gun owners in New York City

On the list: As well as Journal News the website Gawker published a 446-page list of licensed gun owners in New York City