In many ways

Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995, sometimes known as

Halloween 666: The Origins of Michael Myers) and

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (released in 1996 but filmed in 1994, also known as

The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre) are two films that could have only been made in the mid-, pre-

Scream

1990s. While some of my younger readers who did not experience those

dark days may find this hard to believe, but there was actually a time

(i.e., the above-mentioned era) when horror movies were the epitome of

geekdom and unhipness. Nobody (other than weird kids with a subscription

to

Fangoria, such as your humble author) watched such things, or at least wouldn't admit to it.

The

slasher craze

that had begun in the 1970s and had turned into a bona fide pop-culture

staple by the 1980s had run its course, with the bulk of the classic

franchises --i.e.

Halloween,

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,

A Nightmare on Elm Street,

Friday the 13th, etc --having largely become self parodies by this point in time (okay, the

Friday the 13th

series was always kind of a parody to begin with) while new would-be

franchises were largely lacking in fresh vision. There were exceptions,

of course.

Wes Craven's New Nightmare was arguably the strongest

Freddy Krueger film since the original and offered an almost

8 1/2-esque (or at least,

Cat in the Brain-esque) take on the popular series while the original

Candyman offered a compelling take on

Clive Barker's brand of horror working (very loosely) within the confines of American slasher film, for instance.

But these films were largely ignored, with American audiences focusing on such "highbrow" interpretations of

Gothic horror novels such as

Bram Stoker's Dracula,

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and the homoerotic-laden

Interview With the Vampire

adaptation when indulging in such things. As a result those filmmakers

still working in slasher flicks, especially the long-standing franchises

whose names alone could still sell tickets to geeks like me, began

incorporating increasingly grandiose plot lines into these films in a

bid to keep audiences interested. One such plot device, used by the

Halloween and

Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchises respectively, was to incorporate Satanic cults into their mythologies.

Of course the subject of Satanic cults has been a longtime favorite of

horror films but when such elements were incorporated into these

franchises it came during a curious era. The 1980s had witnessed an

explosion of the so-called "

Satanic cult hysteria" fueled by numerous accounts of alleged Satanic cult survivors such as

Michelle Remembers and

Satan's Undedrground. More fuel was added to the fire in 1988 when Maury Terry published

The Ultimate Evil, a radical reinterpretation of the notorious "Son of Sam" killings in which the convicted perpetrator,

David Berkowitz,

was depicted as a member of a nationwide Satanic cult network

involved in a host of criminal activities and linked to other serial

killers, including

Charles Manson and his family.

While "Satanic cult hysteria" had begun to subside somewhat by the

mid-90s it was still a part of the national debate (especially in the

wake of the "

West Memphis Three"). Beyond that, conspiracy theories were beginning to gain a certain degree of mainstream acceptance in the wake of

Iran-Contra,

Ruby Ridge and

Waco: Talk radio was all the rage with conspiratorial personalities such as

Art Bell and even

William Milton Cooper gaining nation wide audiences;

Oliver Stone had recently released his big-budget and star-studded conspiratorial examination of the

Kennedy assassination,

JFK, while

The X-Files was one of the hottest (and certainly the coolest) shows on TV.

With all of these things converging at once it's understandable that the producers behind the

Halloween and

Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchises

were willing to take some bold steps in terms of the mythology of

their respective series and run with the Satanic cult angle. Still, it

is a bit remarkable that the studios were willing to give them the

money for such ventures, and indeed, they seemed too ultimately regret

this decision --both

Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers and

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generaion would face a host of problems throughout their respective productions (and beyond), as we shall see.

I shall begin first with the after mentioned

Halloween film, the sixth in the franchise. The cult element was not introduced in this film but rather in the one that preceded it (

Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers)

and it was a brief introduction at that, consisting primarily of the

revelation that Michael and the mysterious Man in Black who rescues the

Shape from the sheriff's station at the end of the film both share an

identical tattoo on their wrists. Why this plot line was even

introduced into the franchise in the first place is something of a

mystery. Dan Farrands, who wrote the original screenplay for the sixth

Halloween film, had the following to say about the origins of this plot device in

an interview with Fright:

"When we filmed Halloween 6 in Salt Lake City, where they had done 4 &

5, some of our crew came from those earlier films. I got friendly with some of

them and I asked them questions. And I remember asking what had gone on with

Halloween 5? Why did certain things happen the way they did with that

film? What were the director or writer's intentions? And the response I'd always

get is... nobody knew. They were making things up as they went along. And the

director (of 5) from what I understand was very big into ancient superstitions

and the idea of introducing some kind of black magic. So, I think he would come

to the set with these ideas about bringing some of the black magic to the plot.

I had one conversation with one of the screenwriters, Michael Jacobs, and I

asked him while I was writing the script, 'Can you guys give me a hint here? I

want to be true to what you had set up.'

"And his take was, 'We didn't know what any of it

meant.' There was really no answer as to what all this stuff about runic symbols

and the man with the black coat and the strange cowboy boots was all about. This

all came from the director of Part 5. So since no one had any idea as to what

this mysterious man in black or about the symbol on his wrist was about, I was

free to go my own path with it."

|

| Dan Farrands, scribe of Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers |

I've been able to find little on the director of the fifth

Halloween film,

Dominique Othenin-Girard, and even less about his motivations for introducing the cultic elements into the

Halloween franchise. He seemed to indicate that longtime franchise producer

Moustapha Akkad had something to do with this plot device in

an interview with HalloweenMovies.com:

"The 'Man in Black' character was inspired by Mr. Akkad during the filming. His

concern was how to add an additional hook for the next sequel. So I created the

character without knowing his exact origin, created on-the-fly per se. I

considered him as a soul brother to Michael who came from far to get to Michael.

I was conscious enough to give freedom of interpretation to the next team of

creators (for H6) as to who he really is. I was attentive not to lock them in a

too tight position, so they could play that card as they wished. On the set, I

found the idea of the 'mark' (the Thorn tattoo) to link him to Michael and drew

on them and on the wall my own 'Rune'."

|

| Dominique Othenin-Girard (top) and Moustapha Akkad (bottom) |

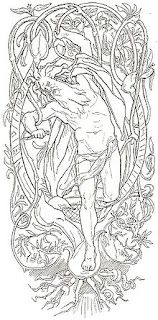

The rune, also known as

Thurisaz and Thurs, was a most curious addition indeed.

Runes were a major part of Germanic and Nordic paganism, having allegedly been given to man by the god

Odin (also known as Wotan), the "All Father" and chief deity of their pantheon.

"He won the knowledge of the Runes, too, by suffering. The Runes were

magical inscriptions, immensely powerful for him who could inscribe them

on anything -- wood, metal, stone. Odin learned them at the cost of

mysterious pain. He says in the Elder Edda that he hung

Nine whole nights on a wind-rocked tree,

Wounded with a spear.

I was offered to Odin, myself to myself,

On that tree of which no man knows.

He passed this hard-won knowledge on to men. They too were able to use the runes to protect themselves."

(Mythology, Eddith Hamilton, pg. 455)

Joseph Campbell offers a less fantastical origin for the runes:

"First of all, we have the evidence of the runic script, which appeared

among the northern tribes directly after Tacitus's time. It is now

thought to have been developed from the Greek alphabet and the

Hellenized Gothic provinces north and northwestward of the Black Sea.

Thence it passed -- possibly by the old trade route up the Danube and

down the Elbe --two southwestern Denmark, where it appears about 250

A.D. and whence the knowledge of it was soon carried to Norway, to

Sweden, and to England. The basic runic stave was of 24 (3×8) letters,

to each of which a magical -- as well as a mystical -- value was

attributed. In England the number of letters was increased to 33; in

Scandinavia, reduced to 16. Monuments and free objects throughout the

field of the German Volkerwanderung bear inscriptions in these various

runic scripts, some telling of malice, others of love. For instance, on a

late seventh century stone standing in Sweden: 'This is the secret

meaning of the runes: I hid here power-runes, undisturbed by evil

witchcraft. In exile shall he die by means of magic art who destroys

this monument.' And on a six-century metal brooch from Germany: 'Boso

wrote the runes -- to thee, Dallina, he gave the clasp.'

"The invention and diffusion of the runes mark a strain of influence

running independently into barbarous German north, from those same

Hellenistic centers out of which, during the same centuries, the

mysteries of Mithra were passing to the Roman armies on the Danube and

the Rhine. We did not know what 'wisdom' was carried with the runes at

that early date, but that in later times their mystic wisdom was of a

generally Neoplatonic, Gnostic-Buddhist order is hardly to be doubted.

Othin's (Wodan's) famous lines in the Icelandic Poetic Edda, telling of

his gaining of the knowledge of the runes through self-annihilation,

make this relationship perfectly clear..."

(The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology, pgs. 481-482)

Runes would later be incorporated heavily into Nazi paganism, both for mystical as well as political reasons.

"Further, if runic inscriptions could be found on stones buried or

standing in such faraway places as Minsk or the Pyrenees, then the

assumption was that Minsk and the Pyrenees were once German territories.

"And, if the sounds represented by the runic symbols could be

discerned in place names from other parts of Europe, then it followed

that Germans had once colonized and settled in those places. This was

much more convenient than actually finding runic petroglyphs in situ,

for it meant that merely transliterating the name of a French town or a

Russian River into appropriate runic words (which a clever runic

scholar could do given virtually any cluster of native phonemes from

China to Chile) was equivalent to proclaiming that town or river a

dominion of the once -- and future --German Reich.

"The alphabet was therefore abandoned for mystical purposes by the

pan-German cults in favor of the runes. What was the alphabet, after

all, but some sort of Semetic invention? The runes, on the other hand,

were the pure expression of people of German blood. If a rune were

discovered carved into a stone found lying in a field in Tibet, for

instance, it was simply further proof of Teutoinic migration and

domination. And once the swastika -- a sacred symbol in many parts of

the world that never knew a rune --was identified as a 'rune,' the Nazis

were well on their way to proclaiming the entire globe German

territory."

(Unholy Alliance, Peter Levenda, pg. 51)

The Nazi obsession with runes makes the inclusion of one as a pivotal plot device in

Halloween 6 especially interesting to me.

My personal belief

(based upon my research on such topics) is that if some type of

underground cult network does in fact exist then it most likely derives

from Nazi rituals and "techniques" devised by the

Third Reich

rather than some type of centuries old Satanic conspiracy as is

commonly imagined by the conspiratorial right (though if there is a

centuries old conspiracy I suspect it traces back directly to the

Vatican

itself, a possibility the literature typically downplays if not out

right neglects). But such a topic goes far beyond the scope of this

series.

The sixth

Halloween film may well be the most controversial in

the series among fans. Many felt the series had totally jumped the shark

by making the cultic elements introduced in part five a crucial piece

of the series' mythology. Some fans, however, felt that

Halloween 6 did

a remarkable job of tying the whole series together and provided as

compelling an explanation for the immortal Michael Myers as anyone was

apt to come up with. Daniel Farrands' original script was filled with

allusions to prior films, and even brought back minor characters such

as Tommy Doyle and Dr. Terrance Wynn from the first

Halloween film as major characters. In many ways, the massively overhyped

Halloween: H20 that followed

Curse

after horror's return to hipdom in the late 90s rather blatantly

ripped off many of Farrands' crucial concepts but arguably did not best

its predecessor despite having a decent budget and star-studded cast

(at least by the standards of horror films) at its disposal.

Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers was beset with problems throughout its production. On the one hand, there were the opposing visions of Farrands and director

Joe Chappelle, with the latter naturally winning out. Then there was the studio,

Dimension Films (a subsidiary of

Miramax Films back then), which had its own vision and seemed to regret greenlighting the sixth

Halloween film from the get-go. They apparently held many of Farrands' ideas, such as his desire to cast

Christopher Lee

in the role of Wynn (Dimensions reportedly believed that Lee was too

old and that modern audiences would not recognize him, a notion the

Lord of the Rings

films would soon disprove), in contempt. It nickeled and dimed the

filmmakers throughout, which ultimately led to scream queen

Danielle Harris (who made her theatrical debut in the fourth

Halloween

film and had become something of a child star for the series) dropping

out the day before filming was scheduled to start. Finally, it would

demand hasty re-shoots after an original cut of the film scored poorly

with test audiences. These re-shoots occurred after star

Donald Pleasence

had died and were set to a rigid schedule to meet the film's release

date that ultimately led to filming wrapping up before director

Chappelle had finished. As a result, the theatrical cut ends rather

suddenly with no clear-cut resolution and numerous storylines left

unresolved.

|

| Harris (top, obviously), who briefly attended the same elementary school as Recluse, and Pleasence (bottom) |

Despite these things,

Halloween 6 would prove to be

surprisingly popular amongst the fan base, especially after a bootleg

known as the "Producer's Cut" (in fact, the original cut of the film

that was screened to the above-mentioned test audience) leaked to the

public.

Halloween 6 does a surprisingly effective job of

capturing the zeiteist of the 90s, especially the conspiracy meme.

Director Chappelle was apparently going for an

X-Files-type

feel for this film and it is very evident, especially in terms of the

visuals. The whole conspiracy radio broadcast subculture is also

referenced as well via the character of Barry Simms (

Leo Geter),

a shock jock who comes off as a cross between Art Bell and Howard

Stern, whose broadcast appears in the background of several early

moments in the film. Especially amusing is a caller who insists that the

CIA extracted Michael Myers so that he could be used as an

assassin. Apparently not even Langley could control Myers, the caller

proclaiming:

"They wanted the

ultimate assassin...He took out eight agents when they had him at

Langley. They couldn't control him so they packed him up in a rocket and

shipped him off to space."

As a result of the different versions there is not exactly a uniform

plot line so I will first focus on the theatrical cut and then discuss

the differences in the Producer's Cut as they are relevent to our

discussion.

The film picks up six years after the ending of the fifth

Halloween film, where Michael Myers and his niece Jamie (originally played by Harris, portrayed by

J.C. Brandy in

Halloween 6) were abducted by the above-mentioned Man in Black. As

Halloween 6

opens Jamie, now 15 years old, is giving birth in an abandoned

hospital before a Druidistic cult on October 30. Once this is completed

the Man in Black takes Jamie's baby from her, but a nurse later gives

it back to her and helps her escape. The cult presumably dispatches

Michael, who tracks her down to a farmhouse where he dispatches of her

via farm machinery.

|

| Jamie |

Jamie hid her baby before heading to the farmhouse, however, and it is eventually discovered at a bus station by Tommy Doyle (

Paul Rudd), who was the child being babysat by

Laurie Strode (

Jamie Lee Curtis) in the original

Halloween

film. Tommy now resides in a house next door to the Strode house,

renting a room from a landlady who was Michael Myers' babysitter on the

night that he killed his sister as a child.

The Strode house is currently occupied by Kara Strode, her six-year-old

son Danny, and her parents and brother. Tommy soon deduces that they

are at risk and informs Dr. Loomis (Pleasence), Michael's nemesis since

the first film, of their presence in the Strode house as well as of

Jamie's baby. Both Loomis and Tommy work to extract the Strodes from

their home, but only Kara and Danny make it out, with the rest of the

family being picked off one by one.

|

| Michael doing his thing in the Strode house |

Tommy takes Kara and Danny back to his room and lays out some startling

revelations concerning Michael's links to the rune of thorn.

Specifically, he

states:

"...Runes were a kind of early alphabet that originated in Northern Europe thousands

of years ago, around 500 B.C. Cults used Thorn carvings in blood and pagan

rituals to portend future events and invoke magic. Black magic. Of all the

runes, Thorn had the most negative influence. Thorn may be a reason to explain

Michael’s evil.

"In ancient times, the druid priests believed that Thorn caused sickness,

famine, and death to hundreds and thousands of people. It represented a demon.

Translated literally, it was the name of a demon spirit that delivered human

sacrifices... One child from each tribe was chosen to be inflicted with the

curse of Thorn to offer the blood sacrifices of its next of kin on the night of

Samhain.

"When applied directly to another person, Thorn could be used to call upon them

confusion and destruction -- to literally visit them with the Devil.' The

sacrifice of one family meant sparing the lives of an entire tribe. For years

I’ve been convinced that there’s some reason, some method behind Michael’s

madness, and the common link I’ve found is Thorn...

"Well then Michael’s power would end, and the curse would be passed on to another

child. That’s why I think these people, whoever they are, are after Jamie’s

baby. They must want to make Michael’s final sacrifice...

"The druids were also great mathematicians and astronomers. The Thorn symbol is

actually a constellation of stars that appears from time to time on Halloween

night. Whenever it has appeared, Michael has appeared. Coincidence? I’ve traced

it back to 1963 when Michael murdered his sister, Judith. He escaped from

Smith’s Grove sanitarium fifteen years after that in 1978. It happened three

years later in 1981 when he escaped from a routine transfer from Ridge Mont to

Smith's Grove. Seven years later in 1988, and the year after that in 1989. And

after six years, Thorn reappears. Tonight."

|

| Michael's "thorn" tattoo (top) and the alleged constellation it represents (bottom) |

Based on what I've been able to ascertain about the rune of thorn, the

film's description is way off. 'Thorn' derives from the Old Norse word

'Thurs,' which means giant. While giants were certainly terrible

creatures in Norse mythology (as well as in most mythologies) there was

nothing especially cursed about this rune. Beyond that the

druids,

whose Celtic religion was slightly different from many of the pagan

practices of mainland Europe, had their own sacred alphabet and did not

employ runes, though there is some overlap between Celtic and Norse

mythology overall (Certainly the Nazis were most interested in the

overlap between Norse and Celtic mythology and incorporated both

elements into their own state religion). In general the chief holidays

of Celtic paganism, of which Halloween/

Samhain was the principal one, were celebrated at different times of the year than those on mainland Europe.

"From the foregoing survey we may infer that among the heathen

forefathers of the European peoples the most popular and widespread

fire-festival of the year was the great celebration of Midsummer Eve or

Midsummer day. The coincidence of the festival with the summer solstice

can hardly be accidental. Rather we must suppose that our pagan

ancestors purposely timed the ceremony of fire on earth to coincide with

the arrival of the sun at the highest point of his course in the sky.

If that was so, it follows that the old founders of the midsummer rites

had observed the solstices or turning-points of the sun's apparent path

in the sky, and that they accordingly regulated their festal calendar to

some extent by astronomical considerations.

"But while this may be regarded as fairly certain for what we may call

the aboriginals throughout a large part of the continent, it appears not

to have been true for the Celtic peoples who inhabited the Land's End

of Europe, the islands and promontories that stretch out into the

Atlantic ocean on the North-West. The principal fire-festivals of the

Celts... were seemingly timed without any reference to the position of

the sun in the heaven. They were two in number, and fell at an interval

of six months, one being celebrated on the eve of May Day and the other

on Allhallow Even or Hallowe'en, as it is now commonly called, that is,

on the thirty-first of October, the day preceding All Saint's or

Allhallows' Day. These dates coincide with none of the four great hinges

on which the solar year revolved, to wit, the solstices and the

equinoxes. Nor do they agree with the principle seasons of the

agricultural year, the sowing in spring and the reaping in autumn.

For when May Day comes, the seed has long been committed to the earth;

and when November opens, the harvest has long been reaped and garnered,

the fields lie bare, the fruit-trees are stripped, and even the yellow

leaves are fast fluttering to the ground. Yet the first of May and the

first of November marked turning-points of the year in Europe; the one

ushers in the genial heat and the rich vegetation of the summer, the

other heralds, if it does not share, the cold and the barrenness of

winter...

"Of the two feasts Hallowe'en was perhaps of old the more important,

since the Celts would seem to have dated the beginning of the year from

it rather than from Beltane. In the Isle of Man, one of the fortresses

in which the Celtic language and lore longest held out against the siege

of the Saxon invaders, the first of November, Old Style, has been

regarded as New Year's day down to recent times... In ancient Ireland,

as we saw, a new fire used to be kindled every year on Hallowe'en or the

eve of Samhain, and from the sacred flame all the fires in Ireland were

rekindled. Such a custom points strongly to Samhain or All Saints' Day

(the first of November) as New Year's Day; since the annual kindling of a

new fire takes place most naturally at the beginning of the year, in

order that the blessed influence of the fresh fire may last throughout

the whole period of twelve months. Another confirmation of the view that

the Celts dated their year from the first of November is furnished by

the manifold modes of divination which... were commonly resorted to by

Celtic peoples on Hallowe'en for the purposes of ascertaining their

destiny, especially their fortune in the coming year; for when could

these devices for prying into the future be more reasonably put in

practice than at the beginning of the year? As a season of omens and

auguries Hallowe'en seems to have far surpassed Beltane in the

imagination of the Celts; from which we may with some probability infer

that they reckoned their year from Hallowe'en rather than Beltane.

Another circumstance of great moment which points to the same conclusion

is the association of the dead with Hallowe'en. Not only among the

Celts but throughout Europe, Hallowe'en, the night which marks the

transition from autumn to winner, seems to have been of old the time of

year when the souls of the departed were supposed to revisit their old

homes in order to warm themselves by the fire and comfort themselves

with the good cheer provided for them in the kitchen or the parlour by

their affectionate kinsfolk."

(The Golden Bough, James Frazer, pgs. 730-732)

Still, the Druid/rune plot line is not as outlandish as it may

seem. Human sacrifices were most likely committed on Samhain and

Beltane by the

Celts,

though it bears emphasizing that these victims were by all accounts

convicted criminals (the execution of which in a ritualistic fashion

occurs in numerous cultures) and not the innocents the conspiratorial

right typically depicts them as.

"Condemned criminals were reserved by the Celts in order to be sacrificed to the

gods at a great festival which took place once in every five years. The more

there were of such victims, the greater was believed to be the fertility of the

land. If there were not enough criminals to furnish victims, captives taken in

war were immolated to supply the deficiency. When the time came the victims were

sacrificed by the Druids or priests. Some they shot down with arrows, some they

impaled, and some they burned alive in the following manner. Colossal images of

wicker-work or of wood and grass were constructed; these were filled with live

men, cattle, and animals of other kinds; fire was then applied to the images,

and they were burned with their living contents.

"Such were the great festivals held once every five years. But

besides these quinquennial festivals, celebrated on so grand a scale, and with,

apparently, so large an expenditure of human life, it seemed reasonable to

suppose that festivals of the same sort, only on a lesser scale, were held

annually, and that from these annual festivals are lineally descended some at

least of the fire-festivals which, with their traces of human sacrifice, are

still celebrated year by year in many parts of Europe. The gigantic images

constructed of osiers or covered with grass in which the Druids enclosed their

victims remind us of the leafy framework in which the human representative of

the tree-spirit is still so often encased."

(ibid, pg. 745-746)

Beyond this, a sacred alphabet was a major feature of druidistic

paganism, though it was not runic per se. They did have something very

similar, however, known as

Ogham inscriptions,

which were likely used initially as a kind of elaborate sign language

before being chiseled into wood and the like when the Druids were in

decline.

"... In Ireland Oghams were not used in public inscriptions until

Druidism began to decline: they had been kept a dark secret and when

used for written messages between one Druid and another, nicked on

wooden billets, were usually cyphered. The four sets, each of five

characters... represented fingers used in a sign language... Each letter

in the inscriptions consists of nicks, from one to five in number, cut

with a chisel along the edge of a squared stones; there are four

different varieties of nick, which makes twenty letters. I assume that

the number of nicks in a letter indicated the number of the digit,

counting from left to right, on which the letter occurred in the finger

language, while the variety of nick indicated the position of the letter

on the digit. There were other methods of using the alphabets for

secret signaling purposes. The Book of Ballymote refers to Cos-ogham

('leg-ogham') in which the signaler, while seated, used his fingers to

imitate inscriptional Ogham with his shin bone serving as the edge

against which the nicks were cut. In Sron-ogham ('nose-ogham')

the nose was used in much the same way. These alternative methods were

useful for signaling across a room; the key-board method for closer

work."

(The White Goddess, Robert Graves, pg. 114)

All of these make the mythology of

Halloween 6 surprisingly apt

at a synchronistic level. In the next installment of this series we

shall apply the rather elaborate mythology screenwriter Daniel Farrands

created for the franchise to the different endings of the sixth

Halloween film and the implications that it implies. We shall also get around to

Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation as well as "the meaning of horror." Stay tuned.

About The Author

About The Author