Mining Bitcoins takes power, but is it an “environmental disaster?”

Also, Adam Smith would be appalled.

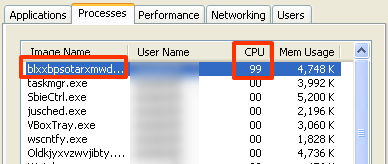

Bitcoin mining takes a lot of computing

power—so naturally someone created a piece of malware to mine on other

people's computers.

Writing in Bloomberg News, Gimein notes that mining Bitcoins—performing computationally expensive calculations needed to define new Bitcoins—uses power. A lot of power. (Read our 2011 Bitcoin primer for more details.) He writes:

About 982 megawatt hours a day, to be exact. That’s enough to power roughly 31,000 US homes, or about half a Large Hadron Collider. If the dreams of Bitcoin proponents are realized, and the currency is adopted for widespread commerce, the power demands of bitcoin mines would rise dramatically.Gimein draws on the stats provided by Bitcoin-focused site Blockchain.info. The numbers fluctuate a bit with each day of calculations being tracked. According to Blockchain's stats this weekend, the last 24 hours of worldwide mining activity burned through 928.24 megawatt hours of power while miners calculated 59,502.6 gigahashes per second. Total power bill: $139,236.07.

If that makes you think of the vast efforts devoted to the mining of precious metals in the centuries of gold- and silver-based economies, it should. One of the strangest aspects of the Bitcoin frenzy is that the Bitcoin economy replicates some of the most archaic features of the gold standard. Real-world mining of precious metals for currency was a resource-hungry and value-destroying process. Bitcoin mining is too.

Critics are already pushing back against the "environmental disaster" claim. Writing in Forbes, Tim Worstall says the energy being used is "simply trivial," amounting to 0.025 percent of the total US household electricity supply. And worldwide, that percentage would be far lower. Besides, Worstall says, "at some point Bitcoin mining will stop. There is an upper limit to the number that can ever be mined; I think I’m right in saying that we’re about halfway there at present. Thus this energy consumption will not go on rising forever. At some point it will come to a dead stop in fact." (The system is self-limiting, with a max of 21 million bitcoins.)

As for the stats themselves, they're fairly speculative to begin with. The computers calculating hashes are assumed to be using 650W per gigahash—which Blockchain freely admits is an estimate that depends entirely on the efficiency of one's computation hardware. In addition, Blockchain assumes the cost of electricity to be 15 cents per kilowatt hour; here in Chicago, it's only one-third that number. Neither the amount of electricity used nor the cost of that electricity is a number worth putting a huge amount of faith in.

Regardless of the environmental impact, though, writers like Nobel laureate Paul Krugman see Bitcoin mining as a terrible step backwards for currencies. He cites Adam Smith on "the fundamental foolishness of relying on gold and silver currency, which—as he pointed out—serve only a symbolic function, yet absorbed real resources in their production, and why it would be smart to replace them with paper currency."

"And now here we are in a world of high information technology," Krugman wrote this week in the New York Times, "and people think it’s smart, nay cutting-edge, to create a sort of virtual currency whose creation requires wasting real resources in a way Adam Smith considered foolish and outmoded in 1776."

Still, Bitcoin has its boosters. Look no further than the Winklevii, who say they control one percent of the currency.

No comments:

Post a Comment