How the FBI cracked a “sextortion” plot against pro poker players

"We don't just fly out here and kick in your door knowing only a little."

Aurich Lawson / Thinkstock

At the top of the staircase before them stood their target, Keith Hudson. "Show your hands!" demanded one agent. "FBI!" Hudson did not immediately comply; instead, he stepped back from the stairs and said he had to get his daughter. The agents commanded him to stop. Hudson did so, backing down the steps. He was handcuffed when he reached the bottom.

Outside and down the street, the force behind the search warrant was sitting in her car, waiting for the all clear. Special Agent Tanith Rogers had flown up from the FBI's Los Angeles office, where she had spent the last month flying across the country to investigate an online extortion plot. A key agent in the FBI's Cyber Division, Rogers had most of her answers already—the investigation documented in six notebooks stuffed with material—but she wanted Hudson to fill in some of the gaps. And to own up to what he had done.

Rogers entered the home with her partner, Special Agent Karlene Clapp, and the pair made sure that Hudson's three-year old daughter was taken care of before leading Hudson into his daughter's upstairs bedroom.

"I'm harmless," Hudson told them.

"But we're not," Clapp said lightly. It was a joke—sort of.

Hudson's handcuffs were removed; the bedroom door was closed. Hudson sat in a chair facing Clapp and Rogers. Advised that he had the right to remain silent and that he was not under arrest, Hudson nevertheless spoke to the agents. For two hours, the conversation revolved around a simple enough crime: someone had broken into the Hotmail account of professional poker player Joe Sebok and had grabbed copies of sexually explicit images featuring Sebok, which had been stored there as attachments. The mystery man then contacted Sebok repeatedly, demanding wildly varying sums of cash to keep the images under wraps. When Sebok did not comply, the extortionist released a pair of images to key people in the poker community.

“Did I really threaten to kill him?” Hudson asked.The trail had turned up two sets of IP addresses. One belonged to Hudson, showing that he had looked at the images from within Sebok's Hotmail account. Hudson admitted to what the agents already knew, but he argued that extortion was the furthest thing from his mind; he had been, he said, simply helping out an online acquaintance, a college student and poker fanatic named Tyler Schrier, who had provided the login. Hudson said that Schrier, working from his dorm room in Connecticut, was the real mastermind.

Rogers was contemptuous.

"I am not going to lie to you," she told Hudson as the three spoke in the child's bedroom. "If you want to ask me any questions, I will tell you the truth. Here is what is going on right now: you're being silly. I know that you broke into Joe's account because I can show that your IP did it... So if you're going to lie, that's only going to make you look worse because here is what I have right now. I have three counts of extortion, and—I don't know—five or six counts of intrusion... This is where you get to decide if you want to be a witness or if you want to be a suspect. I know that you're lying because I can prove it."

"OK, I am not trying to lie to you..." Hudson said.

"The FBI does not fly us out here and we don't break into your door to talk to you if we don't have a substantial amount of evidence against you," Rogers said. "If you're going to tell me that some silly child who is in the East Coast and goes to college—who is 20—is the one behind it, I know you're lying."

Hudson, then in his late 30s, insisted it was true. In fact, he said he warned Schrier about what a bad idea blackmailing a pro poker player would be. He had made a screen capture of the images in Sebok's account and e-mailed them to Schrier, he admitted, but not for blackmail. Schrier had told him that his own computer was "too slow" to take the screencaps—Hudson was simply helping out a friend.

As unlikely as this story sounded already, it made even less sense when the agents revealed the other key fact in their possession: they knew that Hudson had urgently been seeking Schrier for weeks. The student had failed to respond to Hudson's increasingly frantic calls and texts and instant messages and e-mails. Hudson had then tracked down Schrier's father and even Schrier's school—apparently getting someone to take a note over to Schrier's dorm room—in his quest to get a response.

Rogers and Clapp suspected the reason for all the communication: Hudson was terrified that Schrier had succeeded in his extortion attempt and was now sitting on $100,000 of cash or more—and that he was going to cut Hudson out of his fair share. Not so, Hudson told the agents; he had simply been concerned about the well-being of his online acquaintance.

“I know it’s bullshit. You know it’s bullshit. The judge is gonna know it’s bullshit.”Which led the two FBI agents to the next obvious question: if this were true, why had Hudson threatened to kill Schrier if the student didn't return his calls?

"Did I really threaten to kill him?" Hudson asked them.

"Yes, you actually said, 'Why don't you call me so I can tell you how I'll kill you,'" said Clapp, who already had access to the instant messages and e-mails exchanged between the two men.

"Oh wow. Yeah, I guess I was frustrated to be honest... I just wanted to hear from him. You know what I mean?"

"No, I don't," said Rogers.

She clearly didn't believe large portions of what she was hearing from Hudson. As the interview concluded, Rogers provided a rousing peroration. "It's bullshit," she told Hudson about his story. "I know it's bullshit. You know it's bullshit. The judge is gonna know it's bullshit.... Own up to it or take your chances, which is crazy, OK, because we're the Cyber Division of the FBI for Los Angeles. It's the best Cyber Division in the country, and if you're gonna come at me with lies and minimize your part in it, it's just gonna piss me off, and that's what's going on right now."

Hudson realized that the time had come to find himself a lawyer.

The interview concluded and everyone headed back downstairs. As the warrant team left the house with several of Hudson's digital devices in tow, one agent looked back in through the window. Hudson stood at the sink, a picture of domesticity, washing the dishes.

The angry extortionist

Six weeks before, on October 18, Joe Sebok found himself locked out of his Hotmail account twice within two hours. He reset the password each time and regained access. He thought nothing of it until the first e-mail arrived from stankylaggg@gmail.com at 7:23pm. Headed "Amanda's Sex Stories," it asked Sebok if he wanted to "buy" back the pictures he had taken with a former girlfriend. Another e-mail arrived at 7:30, a third at 7:33, with more rolling in at 7:35, 7:39, 7:42, 7:45, 7:46, 7:48, 7:52, and 7:58. Eleven more would arrive during the evening.

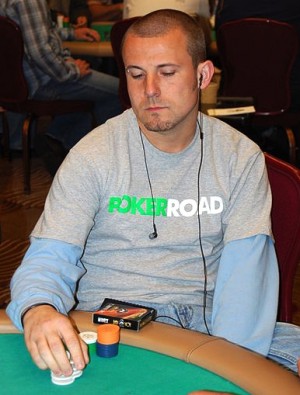

Enlarge / Joe Sebok.

"What are you looking for?" Sebok asked.

The answer came quickly—"100k"—but it also changed quickly. Soon, just4kicksbrah had another plan. "You are going to pay me 60k initially then you are going to pay me 5k every year... the 5k every year will show that I have motivation to never reveal the pictures. This is the easiest way and this is how we are going to do it... If not ill just post the pics."

Sebok took things slow. "i don't know, man. you are blackmailing me. i'ma pay you, but that's a felony crime, bro," he wrote.

"O I thought u were just buying something from me."

"You are telling me you broke into my personal stuff and you aren going to post the pics if i don't pay you," Sebok wrote. "I'm gonna pay you, but that's blackmailing fo sho."

"Fo sho..."

Extortion attempts of this kind always pose a problem of trust: how does the target know that the extortionist will keep his word? Just4kicksbrah guaranteed that payment would keep the pictures private, but Sebok wasn't convinced.

"You can understand your guarantee doesn't mean a whole lot to me when you are blackmailing me for 100k, right?" he wrote.

"Yup but its really your only option if you dont want the pics to go up."

Sebok sent no money, despite his promises to do so. The extortionist continued blitzing Sebok with e-mails and instant messages but quickly expanded his circle of contacts to include Sebok's former girlfriend Amanda and her new boyfriend, who was also a pro poker player. As with those sent to Sebok, these demands for cash were all over the map; one e-mail requested that Amanda "send at least $1000.00 to [a Full Tilt Poker account called] craigslist girl, avatar is the dog." Another e-mail demanded $75,000 by the end of that evening or "I swear to god these pics are out tonight if i dot get the cash." Another asked for $20,000. One requested $1 million.

This e-mail blitz went on for two weeks; Amanda alone received more than 100 messages. The targets of the scheme promised payment but never delivered it. The extortionist's frustration was soon evident. "You told me you would get the cash yesterday," he wrote in early November. "Nothing came. The price has gone up now. I want 40k now. I have other offers for this information now... If you want me to make them private I need the money tomorrow."

Two days later, the price had gone back up to $75,000. The extortionist added, "You guys have fucked with me so much that I am pretty pissed."

What the angry extortionist didn't know was that his targets were simply stringing him along. In the background, the FBI had picked up the case, which ended up on the desk of Tanith Rogers in the FBI's Los Angeles field office. Rogers had always dreamed of being in law enforcement—her favorite TV show as a kid had been CHiPS—and so she had joined her local police department at 21, according to a radio interview she gave for a segment on "remarkable women." But "becoming an FBI agent was sort of like becoming an astronaut," she said. After meeting some agents, she realized that the way to the Bureau was through college, an FBI special agent application, and then training for half of a year at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. She did it all, eventually ending up in the Cyber Division on assignment in Los Angeles, where she quickly developed experience with sextortion cases. She even helped coin the term.

On October 26, only a week after the extortion attempts began, Special Agents Rogers and Clapp received information from Microsoft on every IP address that had recently accessed Sebok's Hotmail account. Most IP addresses clearly belonged to Sebok, but several stood out—including one that resolved to Trinity College, a small private school in Connecticut. The next day, Google responded to Rogers with similar information on the stankylaggg@gmail.com account. Though the account creator had signed up with a bogus name, the "originating IP address" used to register the account resolved to Trinity College.

Rogers and her team sent a subpoena to Trinity, which assigned a static IP address to each particular student device using the campus network. On November 3, Trinity told the FBI that the IP addresses in question were assigned to computer 041e64fd3a80—and that computer belonged to one Tyler Schrier. The student lived in the school's Anadama Residence Hall.

The FBI, racing to assemble its case, interviewed the victims, read through all the e-mails, collected the instant messages, and put together a narrative that involved Schrier and at least one other unrelated IP address—belonging to Keith Hudson up in San Jose.

In the end, the Bureau wasn't quite fast enough to contain Sebok's images. On Friday, November 5, the extortionist sent two photos from Sebok's collection to 100 people in the poker world, including many who worked with Sebok. The images ended up on a well-known poker blog, where a reader submitted them, writing, "Some dude hacked [Sebok's] hotmail and found very graphic emails and one very revealing pic! i bet your wondering how i got it right? well it wasn’t too hard cuz the dude emailed it to like 100 bigtime poker pros, pretty much anyone who's email he had! i cant believe this hasn’t been posted anywhere yet so I thought hey, this would be a great first post here!"

Stankylaggg then e-mailed his extortion targets again, noting that he "sent a small sample out of the Joe stuff I have" and threatening to release more. "This entire issue has really stressed me out," he complained to one of his victims on Saturday, November 6. "I really need 100k if you want to settle this and you want the extra days. If you can get it to me tonight 75k is fine."

On Monday morning, November 8, Rogers called the FBI field office in New Haven, Connecticut and had local agents drive out to the Anadama Residence Hall to get a description needed for the search warrant. She finished drafting the warrant request and its accompanying affidavit, then hopped a red eye flight from Los Angeles to Connecticut. Arriving early on the morning of November 9, Rogers went right to federal magistrate judge Donna Martinez and obtained the warrant she needed. It was time to pay Tyler Schrier a visit.

“I am just so scared”

Enlarge / Schrier's room during the search (with Schrier at left).

FBI

Inside the four-story brick residence hall, the local FBI agents headed to Schrier's room with five campus safety officers and one college vice president in tow. At 6:36am, an FBI agent knocked on Schrier's door and announced the existence of a warrant team. He knocked again with no immediate answer, and campus safety opened the door with an electronic key. The FBI swept into the darkened dorm room, shining flashlights at the startled residents. Schrier's roommate was standing next to the couch, and "it appeared that he had just awakened," according to a later FBI affidavit. Schrier was sleeping on a lower bunk bed, but not for long.

"A 20-year-old undergraduate was routed from his bed and held in another room in his underwear while FBI agents ransacked his bedroom and seized his property," was how his lawyer later complained about the raid. "The manner of execution of this warrant was thus quite abrasive. The manner of execution of this warrant instilled fear and intimidation into Mr. Schrier, which fear and intimidation carried over to the interrogation which followed." (The FBI strongly objected to this description of events.)

Enlarge / The stairwell where Schrier was questioned.

Rogers opened by professing sympathy for Schrier, saying that "I don't really think that any of it was your idea" and asking for his side of the story. Schrier, despite admitting that he was stankylaggg and just4kicksbrah, took the lifeline Rogers had thrown him and agreed that everything had been masterminded by Hudson. It was Hudson who first got into Sebok's e-mail account, Schrier said, Hudson who sent the photos, and Hudson who directed all the extortion attempts.

Indeed, Schrier said, he had actually been the voice of law and order. "I mean basically, [Hudson]—he like told me—like, he, like, told me, like, to contact these people," he said. "He said, like, I do—I do you all these favors, contact these people for whatever... I was like, I really don't want anything to do with this, like, it's just very—it's just not smart ideas... It's against the law and all that stuff. And he's like, naw you gotta do it, you gotta do it... I was like, no I don't want to do this at all."

Yet Schrier admitted to sending hundreds of extortion messages to multiple people for several weeks—and just because some guy "I kind of, like, ignore" had told him to do it? It didn't make sense.

"You can understand that extorting a woman because you're going to post naked photos of her online doesn't look like you are the greatest person in the world," said Rogers. She suspected that Schrier wanted a big cut of whatever extortion money was paid. "So what was the cut suppose to be? You guys were going to get $100,000. You were doing a lot of work."

"I wasn't getting—I wasn't getting any money," Schrier said.

"You weren't getting any of the money?"

"Nope."

"How does that work? That doesn't seem very fair."

As the interview progressed, Schrier appeared to realize the serious trouble he was in. He looked like he might pass out and was given a bottle of water. "I don't wanna get my whole life, like, destroyed," he said. "I am just so scared about how this is going to play out."

"As you should be. I would be scared if I was you too," said Rogers. "We flew out from California on a red eye and [are] flying back tonight on a red eye. You know the government has put a lot of money and time and effort into this case and I will see it through."

The big payday

Three weeks later, Rogers and Clapp were in San Jose for the raid on Hudson's home. Though Hudson and Schrier had different stories to tell, they each had the same type of story: that the other man was the brains behind the operation, that neither had expected to profit at all, that each had acted only to help out a friend, and that each had warned the other of the illegality. The stories couldn't both be true.But the interviews did expose several new bits of information, as Hudson and Schrier each attempted to dish as much dirt as possible on the other. For instance, Hudson bolstered his claim of being a patsy by saying that Schrier had recently extorted some other poker players out of Florida and had actually cleared around $25,000. Schrier and Hudson also revealed that they had gotten into other people's online poker accounts and tried to play the balance into something larger, hopefully to cash out down the road.

And as the FBI agents gradually revealed just how much they already knew, the answers shifted gradually. Near the end of the Hudson interview, for instance, he finally admitted that he had in fact had some thoughts about cashing in on Sebok's pictures. "Maybe we could get $800 or $1,500 was the range I was thinking for the pictures," he said, "like what my friend got when he sent them to Star magazine of Jessica Simpson."

Even this confession made Rogers suspicious. "You're trying to minimize your part," she said. "You're lying a little. I know this. You're admitting to the stuff that you know that we know about. We know about a lot. We don't just fly out here and kick in your door knowing only a little, right?"

"I'm giving you the truth," Hudson insisted. "I'm not the mastermind behind this. I'm not the one breaking into all the shit."

Neither man, in fact, came across as a real "mastermind." Hudson didn't have a job apart from playing poker, and poker "hasn't been that good lately," he said. When his girlfriend showed up at one point during the questioning, she told agents, "I mean, love is blind. I've always wanted him to get a job." Schrier was an All-American wrestler and college student who had left tracks all over the Internet without even attempting to disguise his IP address.

“I feel hella good extorting for profit,” Schrier texted a friend... “If [it] works out I’m getting a 5k place for a week.”In the end, though, questions of motive and leadership proved secondary—accessing Sebok's account was illegal, no matter whose idea it had been. Attempting to extort people was illegal regardless of whether you were just doing it to help out a buddy.

But full answers are preferable to those who spend their lives unraveling puzzles. Before turning the case over to prosecutors, the FBI still had one thread to pull: the digital devices seized during the two search warrant raids. Schrier's cell phone, in particular, was likely to be most useful. An unstoppable texter, Schrier had taken no real precautions in using his phone and had a huge trove of messages relating to the extortion attempt. On January 26, 2011, the LA FBI office obtained a warrant to search the phone, and the contents were damning. Who was the mastermind? Both men looked quite involved.

"I feel hella good extorting [victim Amanda] for profit," Schrier texted a friend on November 2. A week later, the very day that Rogers was in Connecticut securing her warrant from the judge, Schrier texted a friend at Trinity, "If [the extortion attempt] works out I'm getting a 5k place for a week" over spring break.

And the phone was full of texts to Hudson, such as this one from November 5: "We have been doing this for a while this is the big payday we've been waiting for set us up so we can play some real shit."

The consequence-free Internet

The case was eventually turned over to the US Attorney of the Central District of California; an indictment followed in December 2011.Schrier was released on a $50,000 appearance bond put up by his father. He stayed out of trouble for a while, but on October 4, 2012, Schrier broke into another victim's Hotmail account and obtained his online poker account login information. On October 22, Schrier hit another Hotmail account and from there another online poker account. The two victims lost at least $4,000 that they kept as balances in those accounts.

Hudson eventually admitted his part in the scheme, saying that he had accessed Sebok's e-mail account and sent the pictures to Schrier. He also admitted that, through "numerous cellular telephone text messages, defendant and co-defendant Schrier discussed the extortion scheme."

Schrier likewise pled guilty—and not just to the Sebok extortion attempt. He had squeezed $26,000 in extortion payments from a poker player back in August 2010, just as Hudson thought. He had extorted Sebok and his acquaintances. And he had broken into more e-mail and poker accounts while awaiting trial.

How to explain such strangely obsessive behavior—the hundreds of e-mails, the jumpy demands for varying amounts of cash—from a young and intelligent college student? Schrier's family, writing letters to the judge, filled in some of the motivation. Their letters sketched a sad story of a boy born with a cleft palate that had required 13 surgeries to fix, and several surgeries had required serious rehab time at home. As a high school student, Schrier was also diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and given Adderall. And then he discovered online gambling.

It was a potent mix. His sister described how Schrier "used the drug [Adderall] compulsively to study late into the night. It was during this time that my brother became absorbed in online gambling. Sometimes when I woke up in the middle of the night, I could see through a crack in his door that my brother's computer was still on. He was still up. He would then sleep until 3:00pm or later most days. 'Teenage boys are supposed to sleep late, right? It's normal.' That's what my mom and I would try to tell ourselves. But it wasn't normal. In college, my brother was able to get his hands on a dangerous amount of Adderall. My brother began taking a month's worth of Adderall in a week."

When Schrier returned to the family's California home on breaks, he was "rail thin" and "unfamiliar," his family said, with a sunken face and dark circles under the eyes.

"He began fantasizing that the Internet was another world where consequences would not apply to him," wrote his father, who nevertheless promised to do everything within his power to help Schrier recover from this "nightmare."

Tyler's own letter to the judge was wistful: "If I was only able to turn back time..."

The wheels of justice

The pair was sentenced last week in Los Angeles, and Joe Sebok spoke at the hearing.The sextortion "instantly damaged my ability to sustain my livelihood doing what I had been since 2005," he told the judge. "In short, I was no longer able to maintain my then-current level of participation in the poker industry, representing the brands that I had been previously, as well as greatly destroying my ability to do so with new companies moving forward."

Indeed, in 2012 Sebok migrated away from professional poker for a time, moving from Los Angeles up to San Francisco. He took a job in the wine business at a custom crush facility, working shifts from 4am to 4pm during the grape harvest. "I did typical cellar rat stuff," Sebok told the San Francisco Chronicle at the time. "Basically, I came up here and got my ass kicked."

At the sentencing, Judge S. James Otero gave Schrier 42 months in prison. Hudson got 24 months. As for Sebok, he described the entire extortion attempt as "a nightmare, and one I was forced to live through with millions of people watching."

A note on sourcing: The narrative in this case was reconstructed from publicly available court documents, including transcripts of the FBI interviews with Schrier and Hudson. It also drew on affidavits from various FBI agents, the initial and superseding indictments in the case, and the guilty pleas filed by both men. (See docket number 2:11-cr-01175-SJO, USA v. Schrier, filed in the Central District of California.) Joe Sebok's statement at sentencing came from a Department of Justice press release; Sebok declined to comment further for this story.

Similar stories of Internet policing can be found in my forthcoming book, The Internet Police, available this August from W.W. Norton.

No comments:

Post a Comment