FBI denied permission to spy on hacker through his webcam

Feds provide "little or no explanation of how Target Computer will be found."

Sorry FBI, you can't randomly hijack someone's webcam.

A federal magistrate judge has denied

(PDF) a request from the FBI to install sophisticated surveillance

software to track someone suspected of attempting to conduct a “sizeable

wire transfer from [John Doe’s] local bank [in Texas] to a foreign bank

account.”

Back in March 2013, the FBI asked the judge to grant a month-long “Rule 41 search and seizure warrant”

of a suspect’s computer “at premises unknown” as a way to find out more

about this possible violations of “federal bank fraud, identity theft

and computer security laws.”

In an unusually-public order published this week,

Judge Stephen Smith slapped down the FBI on the grounds that the

warrant request was overbroad and too invasive. In it, he gives a unique

insight as to the government’s capabilities for sophisticated digital

surveillance on potential targets. According to the judge’s description

of the spyware, it sounds very similar to the RAT software that many

miscreants use to spy on other Internet users without their knowledge.

(Ars editor Nate Anderson detailed the practice last month.)

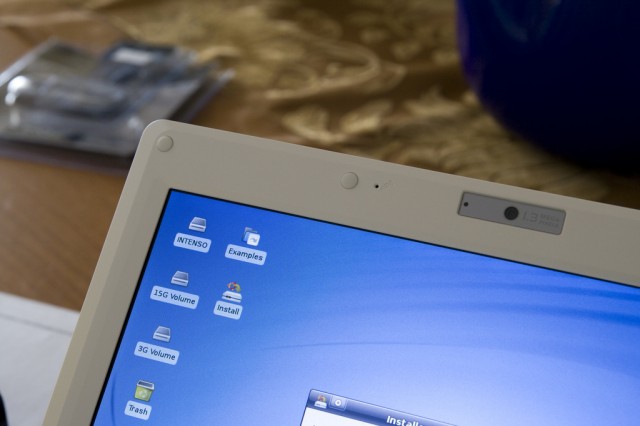

According to the 13-page order, the FBI wanted to

“surreptitiously install data extraction software on the Target

Computer. Once installed, the software has the capacity to search the

computer’s hard drive, random access memory, and other storage media; to

activate the computer’s built-in camera; to generate latitude and

longitude coordinates for the computer’s location; and to transit the

extracted data to FBI agents within the district.”

Neither an FBI spokesperson, nor Craig M. Feazel—who

represents the FBI in this case and is an assistant United States

Attorney—responded to Ars’ request for comment. Many civil libertarians,

though, have raised serious questions as to what the government is up

to.

“Hacking should be something that is the last resort, not

the first option,” Chris Soghoian, principal technologist at the ACLU's

Speech Privacy and Technology Project, told Ars. “No one knows anything

about [how the FBI’s software works]. We know from a [Freedom of

Information Act request] that there was a [Computer and Internet

Protocol Address Verifier software], but this seems to be much more

sophisticated. This sounds like the kind of [spyware] stuff that Gamma or Finfisher is selling. As a general rule, we don’t think law enforcement should be in the hacking business. It’s sexy, but it’s terrifying.”

Soghoian also recalled that Germany’s own (and similar) “federal trojan” program has been revealed to have notable security flaws by the famed hacker group, the Chaos Computer Club.

"Little or no explanation"

According to the judge’s order

(PDF), the FBI has no idea where the suspect actually is, but noted

that the “IP address of the computer accessing Doe’s account resolves to

a foreign country.”

While IP addresses can certainly be easily spoofed,

assuming the suspect actually is outside the United States, that raises

significant questions as to the appropriate use of such a warrant. The

judge agreed, noting that the “government’s application does not satisfy

any [existing territorial limits].”

Further, the judge cited the government’s failure to meet

the Fourth Amendment’s requirement of “place to be searched, and the

persons or things to be seized.”

The Government’s application contains little or no explanation of how the Target Computer will be found. Presumably, the Government would contact the Target Computer via the counterfeit e-mail address, on the assumption that only the actual culprits would have access to that e-mail account. Even if this assumption proved correct, it would not necessarily mean that the government has made contact with the end-point Target Computer at which the culprits are sitting. It is not unusual for those engaged in illegal computer activity to “spoof” Internet Protocol addresses as a way of disguising their actual online presence; in such a case the Government’s search might be routed through one or more “innocent” computers on its way to the Target Computer. The Government’s application offers nothing but indirect and conclusory assurance that its search technique will avoid infecting innocent computers or devices.

The judge also berated the government for its failure to

explain how precisely it would target the suspect’s computer, the

suspect, and no one else.

What if the Target Computer is located in a public library, an Internet café, or a workplace accessible to others? What if the computer is used by family or friends uninvolved in the illegal scheme? What if the counterfeit e-mail address is used for legitimate reasons by others unconnected to the criminal conspiracy? What if the e-mail address is accessed by more than one computer, or by a cell phone and other digital devices? There may well be sufficient answers to these questions, but the Government’s application does not supply them.

Yeah, that Judge Smith

What’s also notable about this case, according to legal

experts, is that it was issued by a Texas federal judge notorious for

his outspoken views on making government surveillance more transparent.

As we reported last year, Judge Smith estimated that tens of thousands of secret surveillance orders are issued by his fellow judges each year.

“This is the first time I've seen a public denial; the government has

been very secretive about this surveillance tool and there hasn't been

much litigation about it that I'm aware of,” Hanni Fakhoury,

an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told Ars. “I'm not

surprised it came from Judge Smith. He's very outspoken on surveillance

issues. His order finding cell site records protected by the Fourth

Amendment is on appeal to the 5th Circuit (EFF argued the case). And he's issued orders denying requests for tower dump and a stingray before too.”

No comments:

Post a Comment