America’s Arcane Origins

Frank Joseph

Political activists of the so-called “religious Right” in the United States never tire of preaching that their country was founded as “a Christian democracy.” But they are wrong on both counts.

When Benjamin Franklin was leaving the first

Continental Congress, he was asked by one of many anxious patriots

waiting outside the courthouse, “What have you given us?” Franklin

replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

The difference might seem trivial or even

non-existent to narrow-minded persons for whom democracy and

dictatorship are the only conceivable forms of government. Yet, the very

word, “democracy,” does not occur once in the Bill of Rights,

the US Constitution, or any state constitution. It was mentioned often

by America’s Founding Fathers, but invariably as a synonym for “mob

rule,” and, along with obsolescent monarchy, an evil to be avoided.

Thomas Paine, the American Revolution’s most

eloquent voice, summed up his colleagues’ view of democracy when he

described it in his world-famous “Rights of Man” as “a species of

demagoguery, wherein clever charlatans, making promises as enticing as

they are impossible to fulfill, win for themselves unwarranted power and

wealth, persuading gullible people to discard their liberties for a

secret tyranny masquerading as public freedom.”

Particularly in the writings of Thomas Jefferson,

the historic models held up for emulation did not include Greek

democracy, but the Venetian and Roman republics. The difference between

these examples most important to men like Paine and Jefferson was the concept

of citizenship. Anyone born in a democratic state automatically becomes

a citizen with all the privileges that entails, including the right to

vote. In a republic, one is not born a citizen, but may only become one

when he or she reaches adulthood; can demonstrate at least a fundamental

grasp of the workings of their government, and is either going to

school or gainfully employed.

In modern America, all that remains of these basic

requirements is a restriction against voting until one’s eighteenth

year. Foreigners must, in fact, pass tests proving their basic

comprehension of the Constitution before becoming US citizens, which

makes them more knowledgeable, discerning voters than native-born

Americans, who are supposed to receive the same kind of rigorous

Constitutional education, but rarely, if ever, do. In demanding at least

some qualifications for

citizenship, America’s Founding Fathers believed that responsible

leaders could only by chosen by a competent electorate. Today, however,

such notions are shunned as “elitist” in most countries described as

“democratic.”

Yet more shocking to bible-beating conservatives, if they were to learn

the awful truth, is that the United States was not founded by

Christians, at least of the kind they would approve. Instead, that

country’s constitutional republic was conceived, fought for and built

almost entirely by deists. While the majority of Americans, then as now,

were at least nominally Christian, most of their leaders were not.

George Washington, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Paul Revere and

virtually all of their intellectual compatriots were deists. The term is

not generally familiar today, but signifies a person who believes in a

universal, compassionate Intelligence that made and orders Creation,

manifests its will through natural law, but requires no religious dogma

to be understood, only the faculty of reason with which every human is

endowed.

Referring to the church of his day, Paine wrote,

“The Christian theory is little else than the idolatry of the ancient

mythologists, accommodated to the purposes of power and revenue… My own

mind is my own church.” Like his fellow deists, who made a clear

distinction between church and state, he was convinced that freedom

meant being able to speak one’s mind on all subjects, religious as well

as political. He did not “condemn those who believe otherwise. They have

the same right to their belief as I have to mine.”

Nor were the deists anti-Christian. They concluded

that Christianity had at its theological core the same mystical truth

found in every genuine spiritual conception; namely, the perennial

philosophy of compassion for all sentient beings as the means by which

the human soul develops. This recognition, however, deeply offended

mainstream Christians, who insisted their brand of faith alone was

correct, all others being heretical at best or demonic at worst.

As an example of the extremes these defenders of the One True Religion

went to demonstrate their piety, hob-nails initialed “T.P.” were sold

by the thousands to Londoners who could walk all day on the name of

Thomas Paine. His treatment in the land he had done so much to free was

more harsh. When he walked through the streets of his hometown in

Bordentown, New Jersey, doors and window shutters were pointedly banged shut as he passed by, while cries of “Devil!” followed him everywhere.

Modern American Christian crusaders would be even more alarmed to learn

that not only was their country founded by deists, but its capitol

deliberately designed as a metaphor for Freemasonry. In his profoundly

researched book, The Secret Architecture of our Nation’s Capital (London:

Century Books, Ltd., 1999), author David Ovason offers abundant

evidence to show that Washington, D.C. was built by Freemasons who

incorporated their arcane, even heretical ideas in the White House, the

Washington Monument, the Library of Congress, the Post Office, the Capitol Dome, the Federal Trade Commission Building, the Federal Reserve Building, even Pennsylvania Avenue itself.

But what is, or was, Freemasonry? Like any idea or

organisation that persists over time, Freemasonry deviated from its

initial purpose until, in the end, it bore only slight, outward

resemblance to its origins. By way of comparison with a group alleged

without much real foundation to have been Freemasonry’s precursor, the

Knights Templar was founded in the early 12th century, ostensibly for

guarding pilgrim routes to Jerusalem with a few soldiers sworn to

poverty and abstinence, but grew to become a virtually autonomous army

richly equipped and armed, finally blossoming into an economic entity so

potent it called down on itself the murderous envy of a French king.

So too, Freemasonry began in 1717 as a fraternity

dedicated to humanitarian, deistic principles for Englishmen unhappy

with the royal powers-that-be, and so were forced to operate with

discretion. By the time early Americans were ready to part ways with the Mother

Country, Freemasonry had spread to their shores and was embraced by

many revolutionaries as an expression of opposition to everything

British, including the Church of England. The secret order continued

to grow in membership and prestige, until it was infiltrated and

perverted from its high-minded ideals by Spartacus Weishaupt, a demented

power-freak who wanted a respectable vehicle for subversion and

insurrection. Separated by a vast ocean from the facts, even Thomas

Jefferson was fooled by Weishaupt’s duplicity.

Henceforward, the “Free and Accepted Masons” were

lumped together with Communists as the secretive enemies of Western

Civilization, and outlawed in most European countries. Even in the

United States, though they were never banned, the Freemasons were under

suspicion by the Federal Bureau of Investigation

for many years, and condemned by several congressmen. Thus criminalized

or under suspicion, their popularity went into a long decline, until

today their once numerous, now largely abandoned lodge buildings, some

still bearing masonic emblems, testify to an aging, dwindling following.

It is wrong, therefore, to parallel the Freemason George Washington,

for example, with the likes of Adam Weishaupt, anymore than it is to

equate George Washington with George Bush.

“The very struggle for independence seems to have

been directed by the Masonic brotherhood,” Ovason writes, “and, some

historians insist, had even been started by them.” Indeed, the War for

Independence began in a warehouse owned by a Mason, and a majority of

the revolutionaries who undertook the Boston Tea Party of 1773 were

Masons. The most famous American Mason was George Washington himself,

although some biographers not altogether happy with Freemasonry have

tried to minimize his association with it. In fact, however, he was the

first Master of the Alexandria, Virginia lodge (Number 22) from April,

1788 until December the following year.

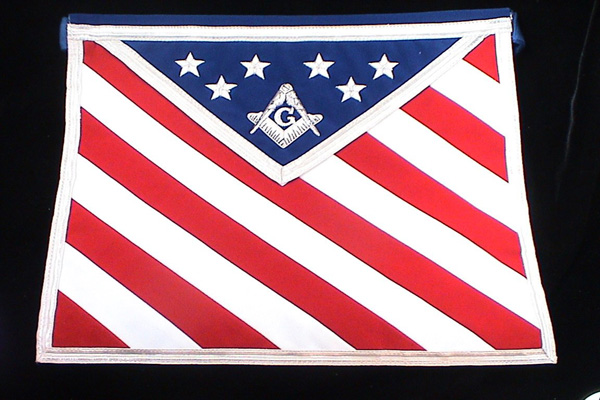

It was this lodge number that was carried before

him on a masonic standard, as Washington, leading ranks of fellow Masons

all wearing their emblematic aprons, walked in procession to the

founding of the American capital, in 1793. The event was commemorated in

a pair of bronze panels designed in 1868. They portray him laying the

cornerstone surrounded by masonic symbols, including the square and

trowel. Washington was still Master Mason when inaugurated as the first

President of the United States on 30 April 1789. After his death ten

years later, he was laid to rest at his Mount Vernon estate in a masonic

funeral, during which all save one of the pallbearers were members of

his own lodge.

Ovason observes in a companion volume (The Secret Symbols of the Dollar Bill,

CA: HarperCollins, 2004) that Washington’s masonic significance was not

only expressed in the city to which he gave his name: “The portrait of

George Washington, at the center of the dollar bill, is highly

symbolic.” The President’s image is centrally framed by the last letter

in the Greek alphabet, an Omega, for “completion”, or the Ultimate, and

implying that the foremost Founding Father represented the apogee of

human values. His appearance on the one-dollar bill is by no means the

only non-Christian symbol found here.

Especially cogent is the

illustration of a truncated pyramid surmounted by a radiant delta

enclosing a single eye beneath the words Annuit Coeptis. A motto on a scroll near the base reads, Novus Ordo Seclorum.

Both were derived from the great Roman writer, Virgil. In his classic

epic, the Aeneid, he directs a prayer for assistance to Jupiter, king of

the gods: Audacibus annue coeptis, or “Favor our daring undertaking!” Novus Ordo Seclorum, “a New Order for the ages,” was taken from one of his famous Ecologues – Magnus ab integro seclorum nascitur ordo, or, “The great series of ages is born anew.”

“The idea of a truncated pyramid was Masonic,”

Ovason writes. It is certainly “pagan,” and generally understood to mean

stability and virtue in the 18th century. According to President

William McKinley, the twenty fifth president of the United States and

himself a Mason, it also meant strength and duration. But these obvious

characterisations only represent the figure’s esoteric aspect. Far less

well recognized, the pyramid depicted on the one-dollar bill, unlike any

in the Nile Valley, has seventy two stones. This amount is hardly

circumstantial, because it has been revered by mystics as one of the

most sacred of all numerals.

Since Pythagorean times, in the 7th century BCE,

and millennia earlier still in ancient Egypt, 72 has represented the

ways of writing and pronouncing the name of the Almighty, not the

Christian or even Old Testament Yahweh, but God as represented by the

Sun, as it moves through space and time. Ovason explains, “Due to the

phenomenon called procession, the Sun appears to fall back against the

stars. This rate of procession is one degree every seventy two years.”

In other words, the dollar bill’s seventy two stones signify the deist

conception of the Supreme Being as rooted in the pre-Christian,

non-Biblical Ancient World.

The single-eyed triangle radiating energy above the truncated pyramid is another Egyptian image, theUtchat, or Udjat,

the all-seeing eye of Ra, a sun-god and the divine king of heaven.

Esoterically, the Utchat was identified with Maat, the moral law

pervading all Creation. Its appearance hovering above the apex of the

dollar bill pyramid not only reinforces the solar symbolism of that

sacred structure, but embodies the principle of Maat America’s Founding

Fathers sought to inculcate in the constitutional republic they

designed.

But the esoteric, deistic, even “pagan” Freemasonry

of America’s Founding Fathers is most apparent in the arcane influence

that Ovason traces throughout the design and construction of the US

capital. These early Americans did not weave this occult symbolism

through their country’s foremost city for clubbish reasons, but because

their iconological signs were the emblems of a new civilization they

wanted to create in the New World.

For New Dawn’s

92nd issue, Jason Jeffrey described in “Washington, D.C.: A Masonic

Plot?” how the White House is located at the apex of a five-pointed star

– the ancient geometric seal of King Solomon, with which he conjured

supernatural powers – formed by the intersections of Massachusetts,

Rhode Island, Vermont and Connecticut Avenues with K Street NW. But the

significance of this urban pentagram is overshadowed by what Ovason has

identified as the city’s chief orientation to Virgo.

He writes that central Washington, D.C. has twenty

public zodiacs, with Virgo prominent in each one. The founding of

Federal City, as it was previously known, laying the cornerstones of the

President’s House, in the wing of the Capitol and the foundation stone

of the Washington Monument, all were timed to coincide with the

appearance of this astrological figure. Ovason shows that the White

House, Capitol building and Washington Monument form a strangely

imperfect “Federal Triangle” that only makes sense when we realize it

identically resembles a configuration made by the stars – Arcurtus,

Spica and Regulus – that bracket Virgo.

On evenings from August 10th to the 15th, as the

Sun sets over Pennsylvania Avenue, the Constellation Virgo appears in

the sky above the White House and the Federal Triangle. At that same

moment, the setting Sun appears precisely above the apex of a stone

pyramid in the Old Post Office tower, which is just wide enough to

occlude the solar disc. According to the 19th century Freemason, Ross

Parsons, “The Assumption of the Virgin Mary is fixed on the 15th of

August, because at that time the Sun is so entirely in the constellation

of Virgo that the stars of which it is composed are rendered invisible

in the bright effulgence of his rays.”

Formal ground-breaking ceremonies for the National

Archives Building were conducted under Virgo. Two years later, three

planets were in Virgo for the official laying of the structure’s

cornerstone. The Federal Reserve Building is replete with a five-petaled

design motif, the symbol of Virgo. The great clock at the Library of

Congress is depicted with a comet in Virgo. Because of its centralized

location, Ovason believes that “the Library of Congress was sited in

this position and its symbolic program established precisely in order to

demonstrate the profound arcane knowledge of the Masonic fraternity

which designed Washington, D.C. … the city was surveyed, planned,

designed and built largely by Masons.” Indeed, no less than twenty one

memorial stones with lapidary inscriptions from various masonic lodges

line the inside shaft of Washington Monument.

But why would they incorporate so many references to

Virgo in their capital? As Ovason points out, the construction of

Washington, D.C. “marked one of those rare events in history when a city

was planned and built for a specific purpose.” He fails to mention,

however, that nearly two hundred years before, the first permanent

European settlement in North America foreshadowed Virgo’s ceremonial

centre on the Potomac River.

In 1606, Sir Francis Bacon

established Jamestown in Virginia, ostensibly named after Elizabeth, the

Virgin Queen. But the emblem he chose, and which survives today as the

state seal, is the image ofPallas Athene, Parthenos, the virgin goddess of Greek myth, the divine patroness of civilization.

Bacon, as Greg Taylor observed in the same issue of New Dawn,

prefigured the Freemasons with his vision of a practical utopia based

on individual liberty and social responsibility – essentially the same

ideals that formed the basis of the US Constitution. When America’s

Founding Fathers came to compose that document, they perpetuated the

identical sacred virginal symbolism initiated at Jamestown.

Repeated symbolism in the architecture, astrological

timing and the very lay-out of Washington, D.C. to Virgo-Virgin Athene

represent homage to the Eternal Feminine, Goethe’s “ewige Weiblicher,”

which, in his “Faust,” leads us onward – “zieht uns hinan.” The

Freemasons who envisioned and constructed the capital of the United

States did so to put their new country in accord with that pure

(“virginal”) energy they believed to actually exist as the demiurge of

Creation. They worshipped that energy, personified in the goddess, a

concept that was anathema to the patriarchal Christians of their time

(and ours?).

As Ovason concludes, “A city which is laid out in

such a way that it is in harmony with the heavens is a city in perpetual

prayer.” Given so great a distance the present occupants of Washington,

D.C. have strayed from the original intentions of its designers, the US

capital needs all the prayers it can get!

Source:

www.newdawnmagazine.com

No comments:

Post a Comment