New Spotify report debunks “per stream” payments for artists

Artists are paid based on popularity, according to Spotify's writings.

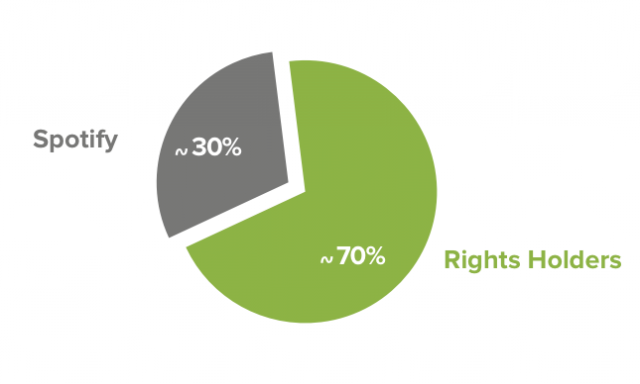

If what Spotify pays out to rights holders

(~70 percent of what they're due, based on popularity), only some of

that may go to the artist themselves.

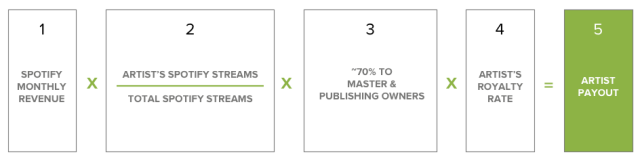

Rather than a flat rate per play of a song, Spotify considers the success of an artist relative to the entire Spotify ecosystem to determine how much money they get. Royalties for, say, one song are paid out based on the proportion of plays it gets out of all of the plays Spotify doles out in a given time period.

There are other factors to the payout formula. How much revenue Spotify earns in a month determines the total amount of royalty money available on a country-by-country basis. After that, Spotify does the math on how much traffic a given artist constituted for the month. For instance, if Spotify has $100 in royalty money from one country and an artist represented 0.01 percent of that month’s streams, the payout for that country would be 0.01 cents.

Enlarge / Popularity is everything.

The report comes as a response to individual artists reporting the money they’ve earned from the service, which often appears to be piddling and is almost always reported as “per stream.” Musician Zoe Keating revealed in August that she earned $808 from 201,412 streams of her two albums on Spotify, a return of 0.4 cents per play, during the first six months of 2013.

According to Spotify’s accounting, Keating’s return is low. Spotify claims that it’s putting out “an average 'per stream' payout to rights holders of between $0.006 and $0.0084” (0.6 to 0.84 cents). And while a per-stream rate can be reverse-engineered from an artist’s total payout, Spotify was actually using the proportional system above to determine payout instead of the sheer number of plays.

Artists have noted in the past that Spotify appears to pay differently per stream depending on whether that stream was by a paid-premium user or a user whose listening is ad-supported. Spotify states that this is a factor in determining the overall revenue pot, but the company doesn’t include it in the formula for determining the revenue per artist.

In November 2012, musician Damon Krukowski wrote on Pitchfork that Spotify negotiated royalty rates individually for each label, and that his label received the “going ‘indie’ rate” of 0.5 cents per play. This was then adjusted per some of the factors above outlined in “small, invisible print,” like the number of listeners who are subscribers vs. ad-supported. Krukowski wrote that this meant Spotify should have owed his label $29.80 for 5,960 plays; instead, he was paid $9.18.

Spotify’s story doesn’t quite account for this alleged process, so it’s unclear whether its method changed since last year or if “going rates” are given as a sort of ballpark figure to set expectations. When asked about Krukowski’s account, Graham James, head of US communications for Spotify, told Ars that “the amount that labels get from Spotify is the same across labels." James continued, “I don’t know where he got that information from… it’s incorrect if he’s saying he negotiated a per-stream rate.”

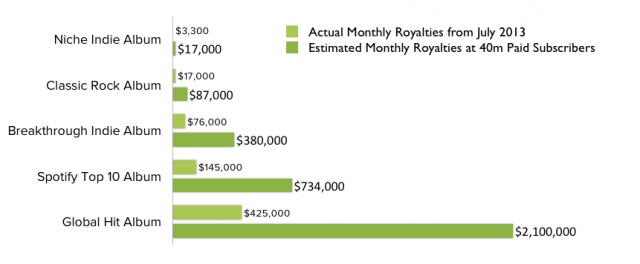

In its report, Spotify goes on to give estimates on what artists of different profiles can expect to earn. Using real, anonymized figures, Spotify states that a “niche indie album” earned $3,300 for the month of July 2013, while a “global hit album” earned $425,000.

Enlarge /

Payouts for different types of albums in July 2013, alongside what

Spotify estimates it will be able to pay once it hits 40 million

subscribers.

Spotify only specifies in the report that these were “actual” numbers, but not whether they were any kind of average or whether the albums were new or recent releases. Mark Williamson of Spotify Artist Services tells Ars that “one [album] is a current top 10 [on] Spotify, one is a current global hit—they’re all fairly current.” The Independent writes that the Daft Punk single “Get Lucky” alone earned $1.08 million on 78.6 million plays. Spotify goes on to make projections about what artists might earn when the service reaches 40 million subscribers, which is what the company estimates its base will be once it “[reaches] a similar scale to Spotify’s most mature markets.” At that point, it says, a niche indie album could expect to earn $17,000 in a month, while a global hit album would get $2.1 million.

Spotify aims to get across in the report that it does not pay artists per stream and that such a figure is inadequate for assessing an artist's value. Spotify revenue is essentially a giant shared pie between artists—one that fluctuates in size depending on subscriber numbers, types, and locations. Once that lump sum is calculated, Spotify determines the size of the artist’s slice based on their proportion of streams. This is in contrast to a radio-style service like Pandora, which does pay a royalty each time a song is played. The Pandora royalty is based on negotiations and not total proportions of traffic.

Such a system doesn't favor bigger artists and huge hit songs, but in an ecosystem like Spotify’s, their popularity appears to cost the smaller artists. The harder a big artist hits with a new song or album, the more streams they add to Spotify’s overall bulk and the smaller everyone else’s payout from the finite, monthly Spotify revenue pool becomes.

All this said, the size of Spotify’s total revenue pool is on the rise. The company has already cracked $500 million in payouts, up from roughly $150 million in 2011. “Our payouts for individual artists have grown tremendously over time as a result of our user growth, and they will continue to do so,” the company writes.

No comments:

Post a Comment