Data brokers won’t even tell the government how it uses, sells your data

They do disclose consumer types like "credit reliant" and "resilient renter."

Companies covered in the report include well-known firms, like Datalogix and Acxiom, as well as credit reporting companies that also trade in consumer data, like Experian and TransUnion. In the report, the committee sets out to answer four questions: what data is collected, how specific it is, how it’s collected, and how it’s used. While the first two questions turned out to be reasonably easy to answer, the companies all but stonewalled the committee on substantial answers to the latter two.

The report harkens back repeatedly to the good old days of data collection, when many of the same companies queried used demographic information like zip codes to help marketers figure out where to send catalogs or area codes to figure out which towns to telemarket to. These days, our many interactions with the Internet—particularly financial ones—have resulted in an onslaught of data for these data brokers to not only collect, but to resell to interested parties.

Datalogix claimed to the committee that it has data on “almost every US household,” while Acxiom’s databases cover 700 million people worldwide. Types of data collected include consumer purchase and transaction information, available methods of payment, types of cars consumers buy, health conditions, and social media usage. Equifax specified that it knew such specific details as whether people have bought a particular kind of shampoo or soft drink in the last six months, how many whiskey drinks a person has had in the last month, or how many miles they’ve traveled in the last four weeks.

What the companies would not specify in full were their sources for consumer data. Three companies, Acxiom, Experian, and Epsilon, would not reveal the sources of their data, citing confidentiality clauses as the reason.

The other data brokers said that their data comes from free government and public databases, along with purchase or license data from “retailers,” “financial institutions,” and “other data brokers,” which were otherwise described as “third-party partners.”

The report mentions that companies acquire social media data specifically for inclusion in their databases. However, this information is difficult to connect to a profile without access to much of the metadata logged by the sites providing those services. Those sites even discourage trying to source that information outside their official avenues; as the report states, Facebook once asked data broker Rapleaf to dispose of data it had obtained by crawling the website. On the other hand, it’s well-known that companies like Facebook and Google re-sell “anonymized” data fed to their services by customers to third parties like these data brokers.

Acxiom also gets data from websites that collect data in exchange for coupons, discounts, or health insurance quotes. Beyond that, Acxiom only stated cryptically that “there are over 250,000 websites who state in their privacy policy that they share data with other companies for marketing and/or risk mitigation purposes.”

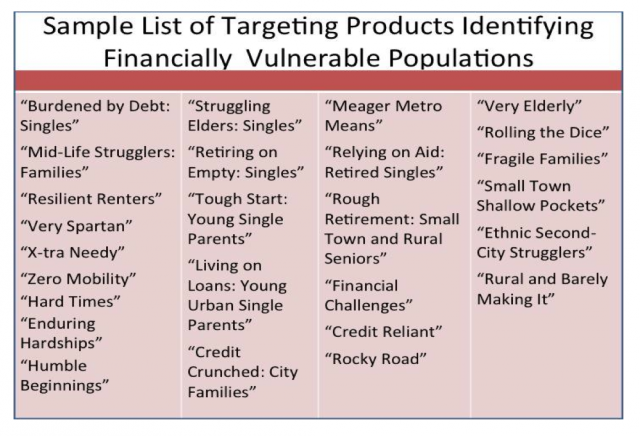

What the companies did reveal was how they package this information internally. Subjects are often scored by data brokers in order to be sold in segments to certain companies on parameters like their ability to be socially influenced or whether they are “frequent ‘text posters.’”

Opt out? Yeah, right...

The report had little to say about how consumers can protect themselves from having data collected on them. A brief section on opt-outs stated that a few of the data brokers offered such an option to customers.But earlier sections indicate that, without a broad-stroke opt-out, a single data broker opt-out would be widely ineffective. For one, the case of Facebook forcing Rapleaf to delete data scraped from Facebook notes that Facebook couldn’t force companies that had bought the data from Rapleaf to delete it. Furthermore, the data source section indicates that data brokers frequently buy or license data from one another. In theory, this would effectively allow them to serve as each other’s backups in the case of an opt out. If a consumer requests deletion from one, the broker can comply and then re-request what it has already shared to its fellow brokers.

The report makes no legislative recommendations, but it encourages policymakers to be conscious of the data brokers’ activity, reminding them that consumers have no legal protection against either data collection or a legal right to know what information is being shuttled back and forth between brokers. As for consumers, the report has little to offer in the way of coping strategies. “They should expect that data brokers will draw on this data without their permission to construct detailed profiles on them reflecting judgments about their characteristics and predicted behaviors,” it concludes.

No comments:

Post a Comment