Did antibiotics spur the sexual revolution?

A cure for syphilis lowered the "cost" of sex, says one economist.

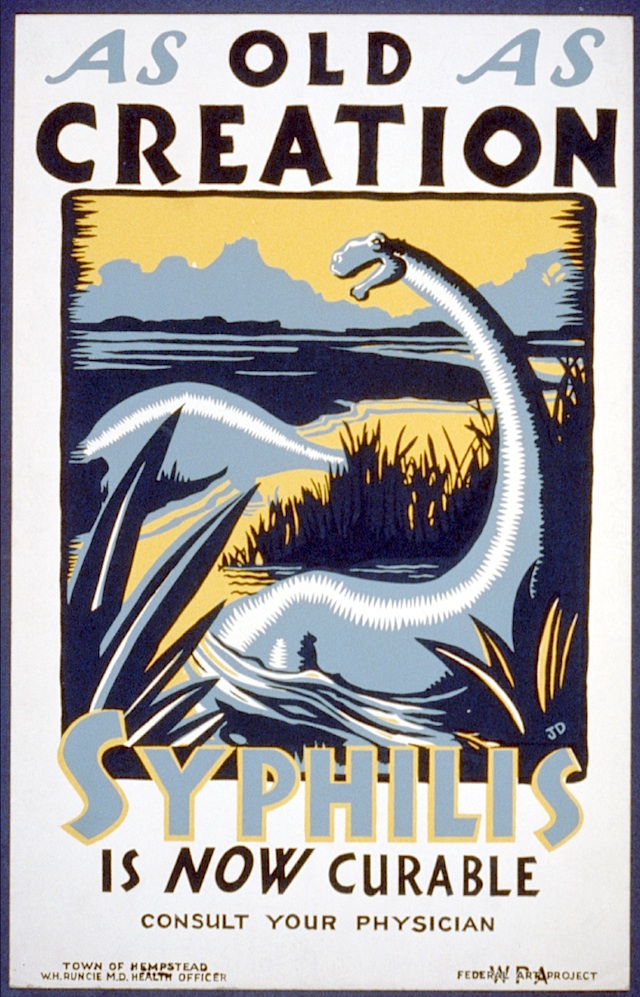

Enlarge / Your tax dollars at work: a WPA poster from the 1930s spreads the news about a cure for syphilis.

One of the traditional explanations for the change in sexual behavior during this era was the development and increasing availability of the birth control pill; sex was less risky if it didn’t lead to pregnancy. But in the latest issue of Archives of Sexual Behavior, economist Andrew Francis argues that it was actually the decline in a different risk—syphilis—that was most important.

In the early 20th century, syphilis was a dangerous sexually transmitted disease without a particularly effective treatment. As of the mid-1940s, more than 600,000 Americans had recently contracted the disease, and the probability that a random sexual partner would have syphilis was more than 1 in 100. But in 1943, penicillin was found to be an effective treatment for syphilis. Infection and death rates from the disease fell sharply, reaching a low in 1957.

Francis’ hypothesis is that the sharply decreasing "cost" of syphilis helped spur changes in sexual behavior in the US over the next decade. The author proposes that the economic principles related to demand can also be used to explain behavior; in this example, when the costs associated with sex decrease, demand increases.

To test this theory, Francis carried out a series of regressions that compared the incidence of syphilis during this era to the rise in what he termed “risky non-traditional sex,” or extramarital sex that could put people at risk for STDs. Francis used three measures to estimate the trajectory of this type of sexual behavior for both whites and non-whites: the rate of gonorrhea infection, the percent of births to teen mothers, and the ratio of births by unmarried women compared to those by married women.

Between 1957 and 1975, the gonorrhea infection rate rose 300 percent, the percentage of both white and non-white teen mothers increased nearly 50 percent, and the extramarital birth rate jumped more than 200 percent.

However, the findings of the study hinge heavily on correlation and, as we all know, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. But the author did investigate alternative hypotheses and found that neither the advent of the birth control pill nor an increase in generally permissive attitudes coincided as precisely with changes in sexual behavior as did the change in syphilis rates.

Of course, many forces play a role in sexual behavior. Francis acknowledges that multiple factors—such as birth control, economic growth, and the inception of Playboy—probably contributed to the sexual revolution of the 1960s. However, the effective treatment of syphilis may have played a larger role in shaping modern sexual behavior than has previously been recognized.

Francis also notes that historical syphilis trends very closely mimic the AIDS epidemic of the last few decades. The rate of syphilis deaths in 1939 was nearly as high as the rate of AIDS deaths in 1995, and the two diseases accounted for roughly the same percentage of deaths in those years. Additionally, studies suggest that a similar increase in risky sexual behavior may have occurred after the development of an AIDS treatment plan, the “highly active antiretroviral therapy.”

The author's conclusion: using economic principles to understand how the costs of syphilis, AIDS, and other sexually transmitted diseases affect behavior may improve decisions about health policy during future epidemics.

Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2013. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-012-0018-4 (About DOIs).

No comments:

Post a Comment