Sunk: How Ross Ulbricht ended up in prison for life

Inside the trial that brought down a darknet pirate.

Aurich Lawson / Thinkstock

Our own Joe Mullin attended every

session of Ross Ulbricht's criminal trial in New York and filed a series

of dispatches for Ars Technica earlier this year. They form, along with

additional reporting, a complete account of the cybercrime "trial of

the century"—which ended today with Ulbricht's sentencing in that same

New York courthouse.

On October 1, 2013, the last day that Ross Ulbricht would be

free, he didn't leave his San Francisco home until nearly 3:00pm. When

he did finally step outside, he walked ten minutes to the Bello Cafe on

Monterey Avenue but found it full, so he went next door to the Glen Park

branch of the San Francisco Public Library. There, he sat down at a

table by a well-lit window in the library's small science fiction

section and opened his laptop.From his spot in the library, Ulbricht, a 29-year-old who lived modestly in a rented room, settled in to his work. Though outwardly indistinguishable from the many other techies and coders working in San Francisco, Ulbricht actually worked the most unusual tech job in the city—he ran the Silk Road, the Internet’s largest drug-dealing website.

Shortly after connecting to the library WiFi network, Ulbricht was contacted on a secure, Silk Road staff-only chat channel.

"Are you there?" wrote Cirrus, a lieutenant who managed the site's extensive message forums.

"Hey," responded Ulbricht, appearing on Cirrus' screen as the "Dread Pirate Roberts," the pseudonym he had taken on in early 2012.

"Can you check out one of the flagged messages for me?" Cirrus wrote.

"Sure," Ulbricht wrote back. He would first need to connect to the Silk Road’s hidden server. "Let me log in... OK, which post?"

Behind Ulbricht in the library, a man and woman started a loud argument. Ulbricht turned to look at this couple having a domestic dispute in awkward proximity to him, but when he did so, the man reached over and pushed Ulbricht’s open laptop across the table. The woman grabbed it and handed it off to FBI Special Agent Thomas Kiernan, who was standing nearby.

Ulbricht was arrested, placed in handcuffs, and taken downstairs. Kiernan took photos of the open laptop, occasionally pressing a button to keep it active. Later, he would testify that if the computer had gone to sleep, or if Ulbricht had time to close the lid, the encryption would have been unbreakable. "It would have turned into a brick, basically," he said.

Then Cirrus himself arrived at the library to join Kiernan. Jared Der-Yeghiayan, an agent with Homeland Security Investigations, had been probing Silk Road undercover for two years, eventually taking over the Cirrus account and even drawing a salary from Ulbricht. He had come to California for the arrest, initiating the chat with Ulbricht—who had been under surveillance all day—from a nearby cafe.

Looking at Ulbricht's computer, Der-Yeghiayan suddenly saw Silk Road through the boss' eyes. In addition to the flagged message noted by Cirrus, the laptop’s Web browser was open to a page with an address ending in "mastermind." It showed the volume of business moving through the Silk Road site at any given time. Silk Road vendors concealed their product in packages shipped by regular mail, and the “mastermind” page showed the commissions Silk Road stood to earn off those packages (the site took a bit more than 10 percent of a typical sale). It also showed the amount of time that had been logged recently by three top staffers: Inigo, Libertas, and Cirrus himself. Ulbricht was soon transferred to a New York federal prison; bail was denied. In addition to charges of drug-dealing and money laundering, prosecutors claimed that Ulbricht had tried to arrange “hits” on a former Silk Road administrator and on several vendors. Though Ulbricht had in fact paid the money, the hits themselves were all faked—in one case, because a federal agent was behind the scheme, in another because Ulbricht appears to have been scammed using the same anonymity tools he championed.

Despite having been caught literally managing a drug empire at the moment of his arrest, Ulbricht pled not guilty. His family, together with a somewhat conspiracy-minded group of Bitcoin enthusiasts, raised a large pool of money for his defense. With it, Ulbricht hired Joshua Dratel, a defense lawyer who has handled high-profile terrorism trials.

Dratel did not reach any sort of plea deal with the government, as is common in such cases. Beyond a general insistence that his client was not, in fact, the Dread Pirate Roberts, Dratel offered no public explanation of what had happened in the Glen Park library—until January 2015, when the case went to trial at the federal courthouse on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan.

"Ross is a 30-year-old, with a lot at stake in this trial—as you could imagine," Dratel said in his opening statement, addressing the jury in a low-key voice. "This case is about the Internet and the digital world, where not everything is as it seems. Behind a screen, it's not always so easy to tell... you don't know who's on the other side."

Ulbricht, he said, was only a fall guy, the stooge left holding the bag when the feds closed in; the “real” Dread Pirate Roberts was still at large. But would the jury buy this unlikely story?

Protesters came out when the Silk Road trial began, but left after the first day.

Aurich Lawson

A criminal eBay

Logging in to Silk Road, users saw pictures of just about every illicit substance imaginable: marijuana, cocaine, LSD, ecstasy—along with pharmaceuticals and designer drugs like DMT. Other items for sale included hacking tools, fake IDs, and even illegal coupons, all of which resulted in additional charges against Ulbricht.In its outlook and operation, the site emulated the legitimate successes of Silicon Valley. The simple interface, extensive user feedback, and extensive user forums, all felt like a cross between Craigslist, eBay, and Facebook.

Silk Road had a founder who truly believed that with the right software, one could both do well and do good. At first, Ulbricht called himself simply "Silk Road," but later he would go by “Dread Pirate Roberts,” or DPR. He and his acolytes believed they were making the world a better, less harmful, more free place, and that they could put an end to the violence that marred so much of the drug trade.

Silk Road didn't have buyers and sellers, it had a "community." Users in the inner circle described Silk Road not as a lucrative business—which of course it was—but as a "movement." Dread Pirate Roberts spoke directly to his users in hundreds of posts, mostly on administrative issues, but he also got emotional. He made time to run a libertarian book club on the site.

Those ideals posed no conflict with the goal of getting rich. DPR and his inner circle viewed government as a cumbersome obstacle, and in that, DPR's ideas weren't so different from what many other Valley CEOs believe, some more privately than others.

Silk Road didn't find or procure drugs itself. The goal was to be a superbly effective "platform," linking up buyers and sellers, and then taking a cut of each transaction. Silk Road took around 10 percent of many sales, but often took smaller commissions. All told, the commission structure proved similar to eBay’s own—an incredible deal when compared to real-world black markets.

Getting onto the site required mastering the use of two technologies, Tor and Bitcoin. Tor, technology originally developed by the US Navy and now overseen by a nonprofit, helped to anonymize Internet use by routing requests through multiple servers, adding and removing layers of encryption along the way. When “dark” Tor-cloaked traffic popped back onto the “open” Internet, tracing it back to its source was difficult. Tor helps everyone who needs anonymity—dissident, drug dealer, and spy alike.

Bitcoin, a novel digital currency based on cryptography, provided a similarly hard-to-trace method of handling payments. Though anyone in the world could watch payments flowing through the Bitcoin system, tying particular accounts to individuals could prove extremely challenging.

Both technologies took effort to master, but neither was particularly difficult. Indeed, Jared Der-Yeghiayan, the HSI agent who became “Cirrus,” taught himself how to use both—and ultimately how to do much more—as he began his two-year journey into the inner circle of Dread Pirate Roberts.

As the site boomed in popularity, it became clear to outside observers and Ulbricht alike that it would become a test case for the strength of the protections offered by Tor and Bitcoin. Could this pair of basic technologies allow a drug marketplace to flourish, safely, in plain sight on the Internet? Ulbricht’s case thus promised to become tech’s early “trial of the century” by showing how online anonymity and cryptography could baffle even highly resourced US investigators—that is, if Dratel could actually prove his claims.

Pointing the finge

When they finally got the chance, it took prosecutors less than a minute to point the finger—literally—at Ross Ulbricht.It was early afternoon on January 13, 2015 when prosecutor Tim Howard got his first chance to speak to the six men and six women of the jury in USA v. Ulbricht.

"That man," Howard said, turning to look straight at Ulbricht and extending his arm toward him, "the defendant—Ross Ulbricht—he was the kingpin of this criminal empire."

As Howard spoke, Ulbricht slowly shook his head back and forth. He looked well-rested, though pale, and wore a suit and tie.

Just several feet behind him, his parents and other family members sat in a row reserved for them. Protesters had stood out front the day the trial began, and some of them had packed up their signs and come inside to watch the opening statements. One sign read, "Web hosting is not a crime—WTF?" Another said "The Chosen One" and showed a picture of Ulbricht superimposed on a Bitcoin logo.

"His idea was to make online drug deals as easy as online shopping," Howard continued. "And that's exactly what he did. A global network of drug dealers paid for the privilege of being on the site. He gave them a way to prevent themselves from being caught. He gave dealers a whole new way to find, and keep, customers."

The site had handled more than $200 million in sales over its brief lifetime. When Ulbricht was arrested, he personally controlled $18 million worth of bitcoins. (The valuation of bitcoin varied enormously over the site's existence.)

Ulbricht's help to vendors, whom prosecutors were always careful to call "drug dealers," was explicit and extensive, Howard said. The site was full of detailed "wikis" explaining how to avoid getting caught and how to package shipments. When disputes arose between dealers and users, Ulbricht reigned as judge.

While the site was fueled by a certain idea of freedom, it wasn't short on rules. There were many, in fact, including a "Seller's Agreement" covering issues ranging from packaging to online security, which vendors had to agree to abide by.

One rule was sacrosanct: no one was allowed to identify other Silk Road sellers or buyers.

"This rule was so important to the defendant that he was willing to use violence to enforce it," Howard told the jury. "When he believed that people were threatening to expose information about Silk Road, he even tried to have them murdered. Now, although those murders were not successful, the defendant paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to get them done."

In the end, he was sure the jury would "reach the only conclusion that is supported by the evidence in this case—that Ross Ulbricht, the defendant, is guilty as charged."

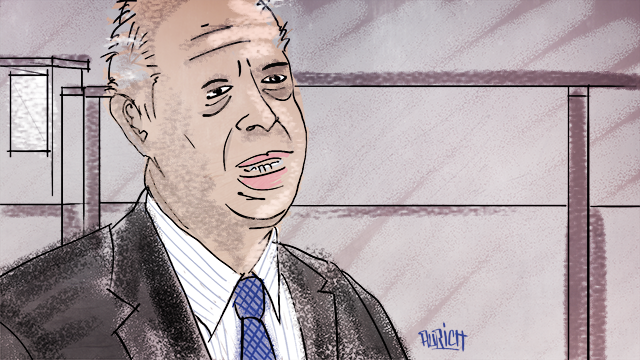

Ulbricht attorney Joshua Dratel.

Aurich Lawson

The obvious problem with this line of defense was that it didn’t explain how Ulbricht ended up in front of his laptop at the Glen Park Library, logged in to the key Silk Road accounts. So Dratel sketched a scenario under which Ulbricht was “lured back by those operators, lured back to that library, that day. They had been alerted that they were under investigation, and time was short for them. Ross was the perfect fall guy."

Dratel argued that his client simply wasn't sophisticated enough to be DPR. Would DPR have gone to the public library that morning and used Silk Road on a public network, at a public library? Would DPR have kept extensive journals on his computer, mixing his business notes and his personal life—as Ulbricht had? Would DPR keep millions in Bitcoin on his computer?

"It defies common sense," Dratel said. "And this is the criminal kingpin the government has described who managed and operated the most profitable Internet black market website in history... handwritten notes in his wastebasket."

US District Judge Katherine Forrest, who was overseeing the trial, stopped for the day just before 5:00pm, a schedule she would adhere to strictly throughout Ulbricht’s three-week trial. She warned the jury, as she would every day, not to speak about the case with anyone, not even close friends and loved ones, and the jurors filed out.

Ulbricht watched until they were completely out of the courtroom, then rose to be returned to his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center. Forrest’s courtroom, on the 15th floor of the Manhattan federal courthouse, was elegantly paneled in dark wood. But Ulbricht came and went through a special side entrance, behind which the walls were cinder blocks painted a prison-industrial white.

A tour of the Silk Road

By the trial’s second day, the smattering of pro-Ulbricht protesters outside the courthouse was gone, and the government's case was in full swing.Jared Der-Yeghiayan took the stand, where he would testify for the next three days. In his early 30s, with close-cropped dark hair and a light beard, Der-Yeghiayan was clearly an experienced witness, shifting his gaze from the prosecutor to the jury as he answered each question.

As an HSI agent stationed in Chicago's O'Hare airport, part of his office's responsibility was hunting for contraband in international mail shipments, much of which came through O'Hare. In 2011, his team began finding more drugs in the mail, particularly ecstasy pills coming from Europe.

On a large screen on the courtroom wall, prosecutors showed a photo of a table full of more than 20 envelopes used to ship drugs. "This was just one day," said Der-Yeghiayan. "We hardly had seizures of ecstasy in years past."

The envelopes, too, looked more professional, often sporting fake business logos, and Der-Yeghiayan suspected that a significant new drug marketplace had come online. In October 2011, he opened an investigation into Silk Road.

Creating a seller account on Silk Road normally required an initial deposit of $500 into the site, which was later refunded. But by September 2012, Der-Yeghiayan had taken over at least one seller's account after arresting that seller—a process he would repeat.

In July 2013, Der-Yeghiayan scored a bigger prize, taking over the account of a Silk Road staffer named “Cirrus.”

"Cirrus has always been dedicated to our community at large," Dread Pirate Roberts explained in a private message introducing Cirrus to his small group of administrators shortly before Der-Yeghiayan took over the account.

Adopting Cirrus’ identity, Der-Yeghiayan earned 8 bitcoins a week—about $1,000 at the time—for moderating forum posts. After several weeks, he got a raise to 9 bitcoins a week. He was paid right up until the Silk Road site was shut down in October 2013.

For two years, Der-Yeghiayan worked the case without ever knowing DPR’s real name; he learned about “Ross Ulbricht” from another office just days before the arrest.

Homeland Security Investigations began making purchases from Silk Road, many of them under an account taken over from an existing site user called "dripsofacid." (Various law enforcement agencies created their own accounts on Silk Road during its existence, but they also took over others after arresting their owners.)

When HSI made their controlled buys, they had the shipments sent to a name and address they used specifically for undercover purchases. Investigators compared the product received to the listing on Silk Road to confirm its origin. One purchase shown to the jury was 0.2 grams of brown heroin, bought from a seller in the Netherlands. The packaging was professional—the heroin tucked inside several plastic bags, which were themselves contained in a vacuum-sealed pouch, which was invisible behind a bluish sheet of paper.

Ultimately, HSI made 52 undercover buys from more than 40 distinct Silk Road dealers in 10 different countries. The drugs were all tested, and all but one purchase resulted in genuine goods. Silk Road, whatever one thought of it, worked as a market.

If you've been living under a cultural rock, the Dread Pirate Roberts was a character from the cult film The Princess Bride (based upon the book of the same name).

Aurich Lawson / ACT III Communications

The “others”

The name "Dread Pirate Roberts" has always been associated with changing identities. In The Princess Bride, a 1973 book later made into a popular movie, Dread Pirate Roberts passes his name and reputation to several successors.In his only press interview, the Silk Road boss likewise said that he had not created the site, but rather bought out the actual founder. "It was his idea to pass the torch, in fact," DPR told Forbes' Andy Greenberg in an August 2013 interview over a secure chat channel. "He was well compensated."

The Forbes story lined up at least superficially with Dratel’s defense that Ulbricht had created a "free market experiment," walked away, and then was "lured back" by the site's real operators to take the fall.

The name of a possible "original” DPR wasn't made public until January 15, the third day of trial. Dratel asked Der-Yeghiayan about any theories he had regarding DPR's identity before finally being turned on to Ulbricht.

"Sometime in the summer, maybe July of 2012, you believed that you had identified the person, right?" Dratel asked.

"I believe that I had a good target for it, potentially," Der-Yeghiayan said.

"A good target—Mark Karpeles, right?"

Karpeles had owned Mt. Gox, formerly the largest Bitcoin exchange. It was the site where most of the world's Bitcoin was exchanged for standard currencies.

Der-Yeghiayan acknowledged that he had considered Karpeles for some time. Der-Yeghiayan had read the Forbes interview and wrote in an e-mail to another agent that DPR sounded a lot like Karpeles.

Karpeles was a "self-proclaimed hacker," Dratel pointed out, who bragged about his computer abilities on Twitter. And Karpeles had racked up a French conviction in absentia for fraud. In addition, an early website advertising the Silk Road, called silkroadmarket.org, had been registered through one of Karpeles' companies.

And then there was the collapse of Mt. Gox.

Mark Karpeles

The Karpeles theory took the courtroom by shock. As Dratel drew it out, a subdued hubbub filled the gallery. The room, more sparse than it had been during the first two days of trial, began to fill again. Reporters who covered the Manhattan court began streaming in, coming up from the press room and other trials.

Under questioning, Der-Yeghiayan admitted that he had written a memo to the Baltimore HSI office, which had opened its own investigation of Karpeles. That office had already seized some Mt. Gox assets and had accused Karpeles of running an unlicensed money exchange. For Der-Yeghiayan, who was looking at Karpeles as the possible head of the Web's biggest drug empire, the Baltimore case was an unwelcome development.

"So you had your own investigation, and that could have been wiped out?" Dratel asked.

Prosecutor Serrin Turner objected, saying the back-and-forth between offices was hearsay.

"I think now is a good time to take our afternoon break," said Judge Forrest with a smile. There was scattered laughter in the courtroom as the tension broke. The jury filed out.

With the jury gone, Dratel made his allegations clearer. Karpeles' lawyers had at one point offered to help HSI with an investigation of Silk Road, in return for some sort of deal with Karpeles, who was never charged. Karpeles, Dratel argued, thus had an incentive to pin the blame for Silk Road on someone like Ulbricht.

"They had this guy in their sights," Dratel said. "Our position is that he set up Mr. Ulbricht."

The evidence of an "alternative perpetrator" could come in, Forrest ruled, but the judge wasn't sure that it should be handled through a cross-examination of Der-Yeghiayan.

Court was coming up on a long weekend. Forrest let the jury go with her standard warning not to speak about the case.

"And don't go watch Princess Bride over the weekend," she added.

Denial

Karpeles responded to Dratel’s allegation within a few hours, first on Twitter and then in a longer message to reporters."This is probably going to be disappointing for you, but I am not and have never been Dread Pirate Roberts," he wrote. "I have nothing to do with Silk Road and do not condone what has been happening there."

In a private message to a colleague of mine, Karpeles added, "It's so ridiculous. I mean, I never did drugs even once in my whole life and I don't really care about all that libertarian thing."

He'd never heard of Ulbricht until his arrest was in the news, he said. As for the silkroadmarket.org site, Karpeles' hosting company may have been chosen simply because it was willing to accept Bitcoin as payment. Anyone could have created the site.

Dratel would continue to insist on what he called Karpeles' "intimate involvement" with Silk Road, but in fact there was nothing substantive tying him to the Silk Road, other than the fact that he had briefly been suspected by law enforcement. (Agents had at one point obtained warrants to search two of Karpeles' e-mail accounts but found nothing to change their conclusion that Ulbricht was the culprit.)

What initially looked like a bold defense would morph into frustrated courtroom theatrics over the next two weeks.

The rabbit was never pulled out of the hat, though; Dratel's increasingly frantic arguments over evidentiary matters were masking a defense that wasn't simply insufficient, it was effectively nonexistent. Dratel would rage when his two expert witnesses, disclosed at the last possible minute, were excluded from trial. But the protests concealed a basic fact—Dratel had no positive factual witnesses to call, no one who could back up Ulbricht's claim to have walked away from the site.

And the government was not exaggerating when it described Ulbricht's laptop as a "mountain of evidence." Over the next two weeks, prosecutors would show hundreds of lines of chats between Ulbricht—or whoever was "me" in his computer's chat logs—and top Silk Road lieutenants. Ulbricht even kept diaries and daily logs on computers, in which he mixed intimate facts from his personal life with notes about Silk Road business. Dratel couldn't explain it, and he didn’t call any witness who could explain it.

Yet Ulbricht's family and a core of true believers continued to cling to the idea that Ulbricht was innocent.

"I could buy anything"

On the first day of the trial, 26-year old Max Dickstein had come dressed in a black ninja costume while holding a poster reading "The Chosen One," featuring a picture of Ross Ulbricht and the Bitcoin logo. Midway through the trial, I bumped into Dickstein again as he smoked a cigarette on the court’s eighth floor balcony with two friends.Beneath a mop of black hair, Dickstein smiles often, in a way that suggests he has secrets to share.

"Rolex!" said Dickstein, thrusting his wrist toward me. "Let's just say I got it on a certain Tor-only marketplace."

"Got it," I said, looking at the gold watch. "Is it real?"

"No!" he said. The trio erupted with laughter.

I had dinner with Dickstein in Chinatown, where he lives. He's an "out-there" libertarian, he explained. His father is a currency trader, and Dickstein, who describes himself as an "unrepentant one-percenter," dropped out of college to trade currency as well. He got his father interested in Bitcoin, which he saw "as an alternative to gold," he told me.

Dickstein wouldn't say on the record whether he'd made buys on Silk Road or other "darknet" markets, but his knowledge of them was extensive. Silk Road had far more traffic than its competitors and had features other markets didn't have, including the ability to "hedge" Bitcoin, which essentially froze the value of the trade at the moment the buyer and seller agreed on it. That protected either side from losing money due to Bitcoin volatility.

Other markets included Black Market Reloaded, which had everything, including guns, which Silk Road didn't traffic in, but it became clear talking to Dickstein that one of the reasons for Silk Road's success was because people trusted it. Much of the credit for that went to DPR himself, who was communicative and helpful. With millions of dollars' worth of bitcoin in the site’s "escrow" system at any given time, nothing could stop a market owner from running with all the escrowed cash. But DPR wasn't like that—he had truly wanted to build the site, and his users believed in him.

I asked him what Dickstein thought about the Ulbricht case; his answer had a kind of duality to it that I would hear from other supporters. If Ross was innocent, then he was a victim and a hero, Dickstein believed. If Ross was guilty—then he was an even bigger hero.

"He created a marketplace where I could buy anything," said Dickstein.

He was even more enthusiastic about the idea of Karpeles getting in trouble. Dickstein was certain that the collapse of Mt. Gox had been straight-up theft by Karpeles, to the tune of $400 million worth of bitcoins—including $16,000 of Dickstein's own.

I asked him how he knew the two other men who'd been smoking on the balcony with him. They met at a 9/11 Truth rally, he explained.

"Building Seven, at least, was brought down by explosives," he said. He had been living near the site at the time with his parents, when just barely a teenager.

I said nothing, but Dickstein could read my skepticism. "Like I said, I'm out there," he told me, smiling broadly.

"We were shocked like everyone else"

Enlarge /

Kirk Ulbricht (left) and Lyn Ulbricht (second from right) visited with

their son, Ross Ulbricht (right), in California weeks before his arrest

in October 2013.

Lyn Ulbricht

Her refrain has always been that Ulbricht's case would have dramatic ramifications for Internet freedom. If convicted, her son would be the first "alleged website host" punished criminally for the actions of his users, she said.

"It's going to be a historical case," she said in an interview with one libertarian activist, Julia Tourianski, who also showed up to the trial. "How much will the government regulate and intrude into the Internet, with precedent set here?"

The Ulbrichts apparently found out that Ross had created Silk Road at the same time everyone else did—when Dratel disclosed it in opening statements.

"There were amazing developments in Ross’ trial this past week!" the family wrote in an e-mail to supporters as trial resumed for the second week. "Ross’ attorney, Joshua Dratel, stunned the courtroom by saying that yes, Ross did create the Silk Road. We were shocked like everybody else."

"Things really changed once Joshua Dratel got up there," Lyn Ulbricht said in a fairly upbeat talk with the editor of Liberty Beat, a libertarian blog that was covering the trial. "The whole room, it just got real. He's expensive, and we need help paying him, because he's brilliant, and he's great, and I believe he can win this—not only for Ross, but for all of us, who believe in Internet freedom."

When I approached her in court, Lyn Ulbricht was upset that a colleague of mine had published her e-mail to supporters, one she initially described as "private." In any case, the "shocked" quote was taken out of context, she said.

"It makes it sound like we're saying Ross lied to us."

The need to raise funds was an imperative for the Ulbrichts, who are not wealthy. They sustain themselves by renting out four vacation cottages on a property purchased in Costa Rica in 1990; during discussions over their son’s bail, which was ultimately denied, they Ulbrichts said that the cottages provide two-thirds of the family income.

Supporters had also raised a great deal of money, including a donation of $160,000 by Roger Ver, a Bitcoin entrepreneur living in Russia. "If guilty, he's a hero," said Ver on Twitter in announcing his participation. "If innocent, he needs help."

"A year of prosperity and power"

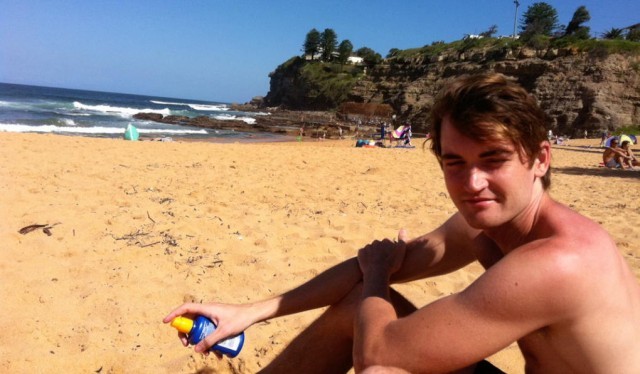

Happier times for Silk Road defendant Ross Ulbricht.

After establishing how Kiernan kept the computer awake, Howard walked the jury through the data pulled from Ulbricht's computer. The stash unveiled during Kiernan's testimony was stunning. In addition to the chat logs with staff, only snippets of which were shown to the jury, the FBI had found code for specific Silk Road pages, including the login page and the "mastermind" page Ulbricht had open in the library. They also found a copy of the site's logo, a nomad riding on a green camel.

Ulbricht was an intensive record-keeper. A spreadsheet labeled "net worth calculator" chronicled what Ulbricht believed he was worth. It ran from August 2006, when he started graduate school at Penn State University ($821) to the moment he launched the Silk Road in 2011 ($29,948),to April 2012 when he had arrived in San Francisco ($384,050). In June 2012 Ulbricht added Silk Road to the spreadsheet as a "hard asset," assigning it the wildly optimistic value of $104 million.

Most revealing, though, were the four entries by Ulbricht in what appeared to be his personal journal. The first, labeled “2010,” described Ulbricht’s unhappiness over the direction his life had taken in Texas.

Ulbricht was unhappy about the problems with "Good Wagon Books," an online used-book recycling business he was involved in. "It was clear that we hadn’t grown the business to the point that it made sense for me to stay on," wrote Ulbricht. "There I was, with nothing. My investment company came to nothing, my game company came to nothing, Good Wagon came to nothing, and then this."

He got a job editing "scientific papers written by foreigners," which he found on Craigslist. But he hated “working for someone else and trading my time for money with no investment in myself." It was then he got serious about Silk Road:

I began working on a project that had been in my mind for over a year. I was calling it Underground Brokers but eventually settled on Silk Road. The idea was to create a website where people could buy anything anonymously, with no trail whatsoever that could lead back to them. I had been studying the technology for a while, but needed a business model and strategy.Ulbricht decided to produce hallucinogenic mushrooms himself so that he could "list them on the site for cheap to get people interested." The journal describes his trip to Bastrop, near Austin, where he rented a cabin "off the grid" and produced several kilos of mushrooms.

Creating the website for Silk Road was difficult for Ulbricht, who was not an experienced programmer at the time. He was also trying to keep up his relationship with his girlfriend Julia, which wasn't easy. The journal describes his feelings at the time:

I had mostly shut myself off from people because I felt ashamed of where my life was. I had left my promising career as a scientist to be an investment adviser and entrepreneur and came up empty handed. More and more my emotions and thoughts were ruling my life and my word was losing power. At some point I finally broke down and realized my love for people again, and started reaching out. Throughout the year I slowly re-cultivated my relationship with my word and started honoring it again.The tone of the paragraph, and its talk about "relationship to my word," appears linked to the Landmark Forum, a popular self-help seminar that Ulbricht was a proponent of. Earlier this year, Eileen Ormsby, who wrote a book about Silk Road before Ulbricht's arrest, noted that the Silk Road Charter appeared to be largely plagiarized from Landmark's own corporate charter.

Ulbricht’s journal entry ended:

In 2011, I am creating a year of prosperity and power beyond what I have ever experienced before. Silk Road is going to become a phenomenon and at least one person will tell me about it, unknowing that I was its creator. Good Wagon Books will find its place and get to the point that it basically runs itself. Julia and I will be happy and living together. I have many friends I can count on who are powerful and connected.The next journal entry was a file called "2011." Ulbricht described himself as working on both Good Wagon Books and Silk Road "at the same time," and learning how to program.

Got the basics of my site written…. Launched it on freedomhosting. Announced it on the bitcointalk forums. Only a few days after launch, I got my first signups, and then my first message. I was so excited I didn't know what to do with myself. Little by little, people signed up, and vendors signed up, and then it happened. My first order. I'll never forget it.The site got "its first press,” a widely-read Gawker article. that led to a spike in signups. But the publicity also led two US senators two attack the site publicly.

The next couple of months, I sold about 10 lbs of shrooms through my site. Some orders were as small as a gram, and others were in the qp range. Before long, I completely sold out. Looking back on it, I maybe should have raised my prices more and stretched it out, but at least now I was all digital, no physical risk anymore. Before long, traffic started to build. People were taking notice, smart, interested people. Hackers. For the first several months, I handled all of the transactions by hand.... Between answering messages, processing transactions, and updating the codebase to fix the constant security holes, I had very little time left in the day, and I had a girlfriend at this time!

“I started to get into a bad state of mind,” Ulbricht wrote. “I was mentally taxed, and now I felt extremely vulnerable and scared. The US govt, my main enemy was aware of me and some of its members were calling for my destruction.”

Ulbricht had made $100,000 from Silk Road and was earning "up to a good $20-25k monthly" at this point. He hired several staffers, especially to help with moderating the forums, a time-consuming job. He met no one in person, only collecting their drivers' licenses and storing them, encrypted, on his laptop.

But it remained Ulbricht alone, in his role as Dread Pirate Roberts, who made all final decisions about what could be bought and sold on the site. A chat with a Silk Road staffer "inigo" shows the two debating the sale of cyanide.

inigo: so uhhh we have a vendor selling cyanideIn a journal entry dated January 1, 2012, Ulbricht reflected on just how revolutionary his work with Silk Road had become, writing, "I imagine that some day I may have a story written about my life, and it would be good to have a detailed account of it."

myself: link please

inigo: getting it now

inigo: not sure where we stand on this

...

inigo: fentanyl has been used to assassinate people too

myself: cyanide has a bad reputation

myself: there are plenty of legitimate uses

inigo: so we're going to allow it?

myself: its bad for image/PR

myself: i think we're going to allow it

myself: its a substance and we want to err on the side of not restricting things

inigo: this is the black market after all :)

myself: it is, and we are bringing order and civility to it

A terrible secret

But Ulbricht had a problem keeping his Silk Road secret to himself.While living near Australia’s famed Bondi Beach in 2011, for instance, his journal records another incident that he immediately regretted. After going for a surf, “I then went out with Jessica,” he wrote. “Our conversation was somewhat deep. I felt compelled to reveal myself to her. It was terrible. I told her I have secrets... It felt wrong to lie completely so I tried to tell the truth without revealing the bad part, but now I am in a jam. Everyone knows too much. Dammit.”

Jessica wasn’t the only person to whom Ulbricht had said too much, either.

On day six of Ulbricht’s trial, the prosecutors called in a gaunt and bespectacled 31-year-old programmer named Richard Bates. Bates had known Ulbricht since the two were in college at the University of Texas at Dallas, and they reconnected when Bates returned to Austin in 2010.

"Did the defendant share a secret with you?" prosecutor Timothy Howard asked Bates shortly after he took the stand.

"Yes, he did," Bates answered, his voice quaking. "He revealed that he created and ran the Silk Road website."

Bates had majored in computer science, and in 2010 got a job at eBay as a software engineer, where he still works. As 2010 drew to a close, Ulbricht, a physics major, began to ask Bates frequent questions about programming, telling Bates only that he was working on a "top secret" project.

Bates kept pressing, though, and one night Ulbricht finally did tell him. The pair logged onto Silk Road using a neighbor's open Wi-Fi network. "I was shocked, but also intrigued," Bates said, and he continued to help Ulbricht with programming.

"What did he offer you in exchange for his help on Silk Road?" Howard asked.

"Nothing but his friendship," Bates said.

In November 2011, Ulbricht had a scare. Someone posted to his Facebook wall, "I'm sure the authorities would be very interested in your site." He went over to Bates' apartment in a panic. Bates told him to shut the site down.

"This is not worth going to prison over," he recalled saying.

But Ulbricht told him he couldn't close the site—because he had already sold it. Bates believed him. The two drifted apart, and Ulbricht eventually left for Australia, moving to San Francisco in 2012.

In a 2013 online chat, Bates showed Ulbricht a news article about Silk Road. "Glad that’s not my problem anymore," Ulbricht wrote back to him. "I have regrets, don't get me wrong…. But that shit was stressful. Still our secret though, eh?"

"Yup," Bates wrote. "I'm spilling the beans when I'm 65, though."

Bates’ story initially seemed to support Dratel’s contention that Ulbricht had gotten out of the Silk Road business early on after seeing what the site had become, but that support was quickly demolished by prosecutors. They showed a conversation between DPR and a mentor of his named “Variety Jones,” in which Jones lectured DPR about getting his alibi straight. Who had he told? "Gramma, priest, rabbi, stripper?" Jones asked.

"Unfortunately yes, there are two," answered DPR. "But they think I sold the site and got out, and they are quite convinced of it."

"Good for that," Jones replied.

Bates got off the stand in the late afternoon. As we walked out of court, he looked about to cry. The government had offered not to charge Bates in exchange for his testimony in the case against Ulbricht. But for the deal, he could have been charged with conspiracy to distribute narcotics just for the programming help he gave to Ulbricht. He also could have been charged for his own drug use, which included purchases of marijuana, MDMA, psychedelic mushrooms, and Vicodin on Silk Road for his own use.

Bates walked past Ulbricht's parents on his way out of court but made sure not to look at them.

A turn in Iceland

After finding Ulbricht and seizing his computer, investigators had as much evidence as they could possibly want in a case of this kind. But what remains unclear—after a long investigation, after extensive pre-trial skirmishing, and even after the trial itself—is exactly how the government latched on to Ross Ulbricht.The story for the jury went like this: IRS Agent Gary Alford, who was one of many federal agents investigating the site, described a simple Google search for the earliest known reference to Silk Road. The thinking was that whoever first mentioned the site to world probably had some hand in its creation.

The first such reference investigators could find was in a post under the name "altoid" on a website called Shroomery.org. In another post under the same user-name, “altoid” provided his personal e-mail address: rossulbricht@gmail.com.

While this gave the government a name, it wasn’t probable cause for a warrant to search the account (something that didn't actually happen until after Ulbricht was arrested). No, the real evidence leading to Ulbricht came from the Silk Road’s server, located in Iceland.

The government hasn't given a clear explanation of how it found that server, which should have been well-hidden, being accessible only via Tor. The official description of the process, that it was the result of an error on the Silk Road login page, was called "implausible" by one of Ulbricht's lawyers. Independent researchers who have looked at it have been even less forgiving, with one saying that the FBI agent who filed the explanation in court simply lied.

The defense may have lost its case even before trial when it didn't try to suppress the evidence from the Icelandic server. With that evidence legally in hand, the government couldn't be stopped from getting the nine other warrants—for other servers, Ulbricht's laptop, his apartment, his Gmail, and his Facebook accounts—and "pen-trap orders" to monitor his IP address and home Internet connection.

Challenging the legality of the FBI’s server seizure, though, would have meant first establishing that Ulbricht had some actual connection to the Silk Road and the machine it ran on. Ulbricht’s lawyers, apparently worried about incriminating their client, did not do so.

In October, Forrest wrote that Ulbricht "failed to submit anything establishing that he has a personal privacy interest" in the server. It was an enormous mistake. In her order, the judge even noted that he could have established such a privacy interest without having it used against him in court. "Yet he has chosen not to do so,” she wrote.

Embracing violence

Private messages, harvested from the Icelandic server by the government, show that DPR was determined not to pay, and soon began looking for ways to find his extortionist.

"I need his real world identity, so I can threaten him with violence," DPR wrote to a new account claiming to be one half of the partnership that was LucyDrop, now called RealLucyDrop. "There's no way I will be handing over cash to somebody who threatens me and this community," he wrote. He demanded FriendlyChemist’s personal details. a name and address. RealLucyDrop said he was a 34-year-old man named Blake Krokoff, who lived near Vancouver with a wife and three kids.

Shortly thereafter, a user named "redandwhite" got in touch with DPR, pretending to be a kingpin affiliated with the Hell's Angels. He was the person FriendlyChemist owed money to, and he was the top of the drug supply chain, he explained. His people "have a majority hold" over most of the movement of products in Western Canada, which is "one of the main drug ports to North America."

Immediately, DPR was solicitous. "FriendlyChemist aside, we should talk about how we can do business," he wrote. "Obviously you have access to illicit substances in quantity, and are having issues with bad distributors."

But first he needed an up-front favor—he wanted redandwhite to knock off his extortionist. "I would like to put a bounty on his head if it's not too much trouble for you," DPR wrote. "Hopefully this is something you are open to and this can be another aspect of our business relationship." After arranging to get paid $150,000 in bitcoins, redandwhite assured him the hit was done. "Your problem has been taken care of... he won't be blackmailing anyone again, ever." Soon, redandwhite offered up more enemies: a user named tony76, whom DPR had long suspected of scamming his users, was actually "Andrew Lawsry," and lived in Surrey.

DPR eagerly took that bait. "This guy has probably ripped off millions of $ at this point from me and the rest of the Silk Road community," he wrote. He paid another $500,000—what the extortionist had asked him for in the first place—to kill Lawsry and his three live-in associates.

In hindsight, it looks like a massive con job. Canadian law enforcement told the FBI that no one was killed in or around White Rock, the town that "Krokoff" lived in. FriendlyChemist, the new LucyDrops, and redandwhite were likely all the same person or group, shifting strategies to try to scam a very rich target. When extortion didn't work, the scam morphed into a plot to kill the extortionist.

Even though they involved mainly people who did not exist, the attempted “hits,” are a deeply complicating factor for Ulbricht and his supporters. Prosecutors have showed transactions in exactly the amounts that DPR agreed to pay for the hits, moving from bitcoin addresses on Ulbricht's laptop, to addresses specified by redandwhite.

On his LinkedIn profile, Ulbricht didn’t mention Silk Road; but he did tell the world he was “creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force.” In the real world, the creators of utopias have often resorted to extreme means to defend their projects; in 2013, as he began to embrace his role as DPR, Ulbricht may have given in to similar temptations.

The incredibly shrinking defense case

The defense's entire case was five witnesses, and it didn't take much more than an hour.Three character witnesses testified in quick succession to Ulbricht's reputation for "peacefulness and non-violence." The fourth witness, Christopher Kincaid, was one of Ross Ulbricht's roommates at his final San Francisco address. He met Ross after posting a room ad on Craigslist, and said, "We had a good feeling about Ross from the first conversation that we had with him." Kincaid didn't know what Ulbricht did for a living, and he took a money order as first month's rent. The final witness was Bridget Prince, an investigator hired by the defense, who read exactly one file from Ulbricht's computer. It appeared to be some kind of Silk Road to-do list.

Ulbricht himself didn't testify, which isn't unusual in a criminal trial. What was unusual is that he waited until the end of the second-to-last trial day to make the decision.

The Ulbricht defense was essentially a non-defense. Dratel had tried to get two experts in to testify, one about Bitcoin and a Columbia University computer science professor. Forrest barred them from testifying in a scathing order that essentially accused Dratel of attempting "trial by ambush." The possibility the defense might want an expert was "long known," and she wasn't even sure the Bitcoin expert was an expert at all.

"Why did the defense choose to proceed as it has?" Forrest wrote. "This Court cannot know. Perhaps a tactical choice not to show the defense’s hand; perhaps to try and accumulate appeal points; perhaps something else."

Either way, the experts weren't getting on the stand. Even if they were, it isn't clear how much they would have helped. Dratel had promised an explanation of what was on Ulbricht's laptop since the beginning of trial, but it never came. No witness could explain away the laptop.

No little elves

Serrin Turner closed the prosecution's case. He blasted the "left and came back theory," which, even if true, wouldn't get Ulbricht out of a conspiracy charge. "There's no dispute [Silk Road] was used to sell drugs," he said. "There's no dispute when the defendant was arrested, he was logged in as Dread Pirate Roberts."In any case, Turner said, it wasn’t true; Ulbricht was the boss, start to finish. Chats and log files on Ulbricht's laptop contained an inseparable mixture of information about Silk Road and Ulbricht's personal life. When DPR wrote in Silk Road's business log that he was sick, Ulbricht e-mailed his parents about being sick; when DPR got hit with poison oak, Ulbricht e-mailed his ex-girlfriend telling her about the same condition; when Ulbricht had an OKCupid date, it was right there in the Silk Road log as well.

"There's no way to explain this away, and the defendant's attempts to do so have been absurd," Turner said. "He's trying to do the old Dread Pirate Roberts play, one more time—on you, ladies and gentlemen.”

"He still thinks he's clever," said Turner as he closed. "It's a hacker! It's a virus! It's ludicrous. There were no little elves that put all of that evidence on the defendant's computer."

"The Internet permits—and thrives, to a certain extent—on deception and misdirection," Dratel said at the beginning of his closing statement. His argument this time was largely reduced to the idea that no criminal mastermind would act as Ulbricht had.

Would DPR have saved his chats? Would he have backed up the site on a thumb drive kept near his bed?

“Keeping a journal like that?” Dratel asked. “Does that sound like DPR? It’s a little too convenient. It’s like a virtuoso piano player who can’t play Happy Birthday. It doesn’t fit.”

"Ross is a hero!"

The jury deliberated less than four hours before convicting Ulbricht on all seven counts against him. In addition to drug trafficking charges, Ulbricht was charged with money laundering, the distribution of fake IDs, and the distribution of computer hacking tools.As the verdict was read, Ulbricht's father held his head. Midway through the reading, Ulbricht turned to face his family and friends, who filled two rows of courtroom benches. He mouthed the words "It'll be okay."

"It's not the end," Ulbricht's mother, Lyn Ulbricht, said to her son as he was escorted from the courtroom and into the cinder block hallway one final time. Several other relatives in front rows simply shouted out quick goodbyes. From the back of the gallery, one supporter shouted, "Ross is a hero!"

Downstairs, Lyn Ulbricht and Dratel told a scrum of reporters gathered outside they would appeal. Both blamed the outcome on the limited case they put on after the judge's evidentiary rulings went against them.

"The defense was shackled," Lyn Ulbricht said. "It's not fair."

The verdict meant that Ulbricht was facing the possibility of life in prison. One of his charges alone, the so-called "kingpin" charge, carries a 20-year minimum. In the first months after the verdict, Ulbricht prepared his appeal and said little about the case. But in May, as his sentencing date drew near, he wrote a letter to the judge. In it, he asked for mercy.

"As I see it, a life sentence is more similar in nature to a death sentence than it is to a sentence with a finite number of years," he wrote. "Both condemn you to die in prison, a life sentence just takes longer. If I do make it out of prison, decades from now, I won’t be the same man, and the world won’t be the same place. I certainly won’t be the rebellious risk taker I was when I created Silk Road. In fact, I’ll be an old man, at least 50, with the additional wear and tear prison life brings. I will know firsthand the heavy price of breaking the law and will know better than anyone that it is not worth it. Even now I understand what a terrible mistake I made. I’ve had my youth, and I know you must take away my middle years, but please leave me my old age."

On May 29, 2015, Ulbricht returned to the Manhattan federal courthouse for sentencing. When he had a chance to speak this time around, he took it.

"I wish I could go back and convince myself to take a different path," he said. "If given the chance, I would never break the law again."

But Judge Katherine Forrest wasn't buying it. "Silk Road's creation showed that you thought you were better than the law," she said. She then sentenced him to life in prison, which he will serve completely unless freed on appeal; the federal prison system offers no parole options.

The last honest pirate?

On the darknet, drugs are still available. But nothing quite like the Silk Road has been seen, before or since. "Silk Road 2.0," launched within a few months of Ulbricht's arrest, lasted less than a year until its alleged creator, 25-year-old Blake Benthall, was arrested in San Francisco.The most popular Silk Road successor, a darknet site called Evolution, shut down without warning in March—when its founders apparently emptied out the $12 million in its escrow system and ran. This sort of "exit scam" was the type of large-scale theft that users of such markets always knew was possible.

Any sense that the darknet could be a safe haven has now been shattered by a series of such arrests and scams. But Silk Road began years earlier, when the dream of creating a cryptographically protected libertarian utopia right in the midst of conventional society still seemed a reasonable proposition. But it was never likely to succeed for long—a fact that Ulbricht has now learned the hard way.

No comments:

Post a Comment