If

you’re the customer of a major American internet provider, you might

have been noticing it’s not very reliable lately. If so, there’s a

pretty good chance that a graph like this is the reason:

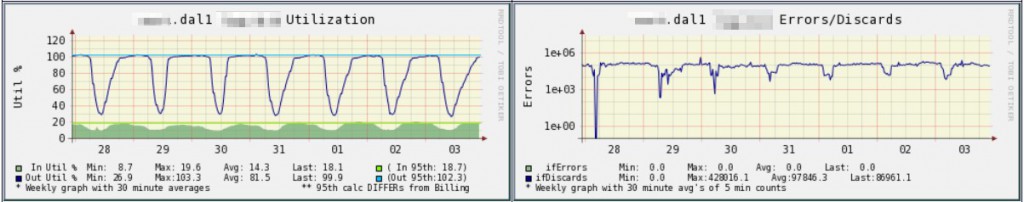

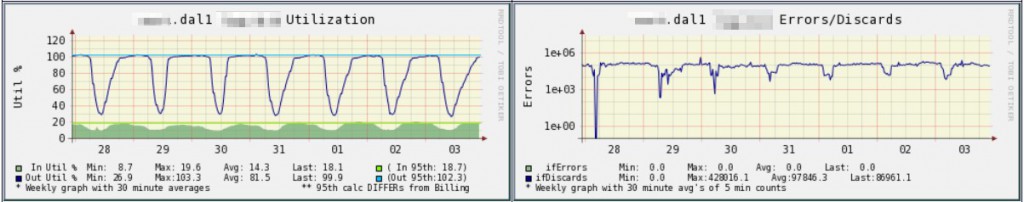

These graphs

comes from Level 3,

one of the world’s largest providers of “transit,” or long-distance

internet connectivity. The graph on the left shows the level of

congestion between Level 3 and a large American ISP in the Dallas area.

In the middle of the night, the connection is less than half-full and

everything works fine. But during peak hours, the connection is

saturated. That produces the graph on the right, which shows the packet

loss rate. When the loss rate is high, thousands of Dallas-area

consumers are having difficulty using bandwidth-heavy applications like

Netflix, Skype, or YouTube (though to be clear, Level 3 doesn’t say what

specific kind of traffic was being carried over this link).

This isn’t how these graphs are supposed to look. Level 3 swaps

traffic with 51 other large networks, known as peers. For 45 of those

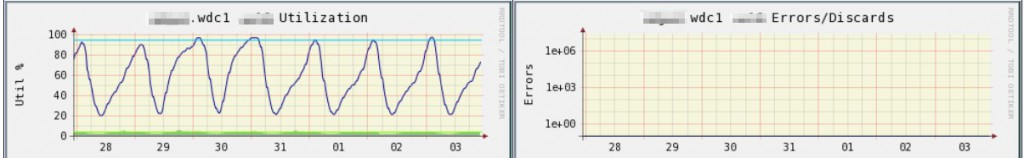

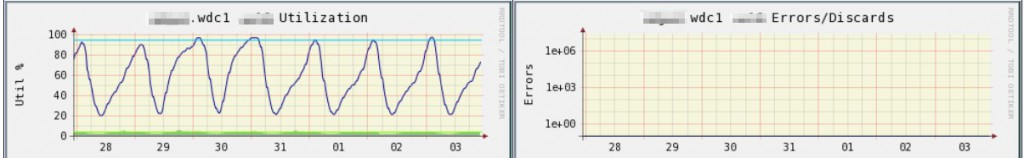

networks, the utilization graph looks more like this:

The graph on the left shows that there is enough capacity to handle

demand even during peak hours. As a result, you get the graph at the

right, which shows no problems with dropped packets.

So what’s going on? Level 3 says the six bandwidth providers with

congested links are all “large Broadband consumer networks with a

dominant or exclusive market share in their local market.” One of them

is in Europe, and the other five are in the United States.

Level 3 says its links to these customers suffer from “congestion

that is permanent, has been in place for well over a year and where our

peer refuses to augment capacity. They are deliberately harming the

service they deliver to their paying customers. They are not allowing us

to fulfill the requests their customers make for content.”

The basic problem is those six broadband providers want Level 3 to

pay them to deliver traffic. Level 3 believes that’s unreasonable. After

all, the ISPs’ own customers have already paid these ISPs to deliver

the traffic to them. And the long-standing norm on the internet is that

endpoint ISPs pay intermediaries, not the other way around. Level 3

notes that “in countries or markets where consumers have multiple

broadband choices (like the UK) there are no congested peers.” In short,

broadband providers that face serious competition don’t engage in this

kind of brinksmanship.

Unfortunately, most parts of the US suffer from a severe lack of

broadband competition. And the leading ISPs in some of these markets

appear to view network congestion not as a technical problem to be

solved so much as an opportunity to gain leverage in negotiations with

other networks.

In February, Netflix agreed to pay Comcast to ensure that its videos would play smoothly for Comcast customers. The company

signed a similar deal with Verizon in April. Netflix signed these deals because its customers had been

experiencing declining speeds

for several months beforehand. Netflix realized it would be at a

competitive disadvantage if it didn’t pay for speedier service. After

its payment to Comcast, Netflix’s customers experienced a

67 percent improvement in their average connection speed.

Netflix has

accused Comcast

of deliberately provoking the crisis by refusing to upgrade its network

to accommodate Netflix traffic, leaving Netflix with little choice but

to pay a “toll.” That might sound like a classic network neutrality

violation. But surprisingly, leading network neutrality proposals

wouldn’t affect this kind of agreement at all.

That’s because Comcast wasn’t technically offering Netflix a “fast

lane” on an existing connection. Instead, Netflix paid Comcast to accept

a

whole new connection. The terms of these agreements, known as

“peering,” have always been negotiated in an unregulated market, and

network neutrality regulations don’t apply to them.

In theory, Netflix’s deal with Comcast doesn’t violate network

neutrality because everyone on this new pipe (e.g. only Netflix) is

treated the same, just as everyone on the old, overloaded pipe gets

equal treatment. But it’s hard to see any practical difference between

the kind of “fast lane” agreement network neutrality supporters have

campaigned against and Netflix paying Comcast for a faster connection.

So why hasn’t interconnection been a bigger part of the network

neutrality debate? Until recently, it was unheard of for a residential

broadband provider like Comcast to demand payment to deliver traffic to

its own customers. Traditionally, residential broadband companies would

accept traffic from the largest global “backbone” networks such as Level

3 for free. So anyone could reach Comcast customers by routing their

traffic through a third network. That limited Comcast’s leverage.

But recently, the negotiating position of backbone providers has

weakened while the position of the largest residential ISPs — especially

Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T — has gotten stronger. As a consequence,

the network neutrality debate will be increasingly linked to the debate

over interconnection. Refusing to upgrade a slow link to a company is

functionally equivalent to configuring an Internet router to put the

company’s packets in a virtual slow lane. Regulations that try to

protect net neutrality without regulating the terms of interconnection

are going to be increasingly ineffective.

No comments:

Post a Comment