One big reason we lack Internet competition: Starting an ISP is really hard

Creating an ISP? You'll need millions of dollars, patience, and lots of lawyers.

Aurich Lawson / Thinkstock

Millions of Americans would gladly switch from their DSL or cable Internet service to fiber, which in many cities delivers speeds of 1Gbps. That's 250 times faster than the 4Mbps download bandwidth that qualifies as "broadband" under the Federal Communications Commission definition. As of Dec. 2012, 29 percent of US households lived in census tracts with one or zero providers offering fixed Internet service of at least 6Mbps, according to FCC data. While the other 71 percent of census tracts had at least two providers offering 6Mbps, they may not offer that speed to all households in each area, the FCC said. Cable and DSL dominate nationally, with fiber-to-the-premises accounting for only 6.7 million out of 92.6 million fixed connections of at least 200Kbps.

Seems like a huge market opportunity, right? But actually starting a new Internet service is no simple task.

A new fiber provider needs a slew of government permits and construction crews to bring fiber to homes and businesses. It needs to buy Internet capacity from transit providers to connect customers to the rest of the Internet. It probably needs investors who are willing to wait years for a profit because the up-front capital costs are huge. If the new entrant can't take a sizable chunk of customers away from the area's incumbent Internet provider, it may never recover the initial costs. And if the newcomer is a real threat to the incumbent, it might need an army of lawyers to fend off frivolous lawsuits designed to put it out of business.

Yes, it's difficult, but that doesn't mean people haven't done it.

"I would compare it to playing Starcraft or maybe Civilization, in that you're trying to accomplish a task, and you have limited resources, and you're trying to balance a bunch of different needs," ISP owner Joshua Montgomery told Ars.

Enlarge / Joshua Montgomery, owner and operator of Wicked Broadband.

But Wicked Broadband hasn't been the success Montgomery hoped, and he's been seeking city funding to help keep the company going. It's a tough business, he said.

"You get out in the community and sell bandwidth, and over time you increase the number of customers paying you, and at the same time balance that with your increased ability to deliver bandwidth," he said. "A lot of times you find yourself in a catch-22. It's like, 'hey I need more bandwidth, but I can't get the bandwidth because I need more money, but I can't get more money because I don't have the bandwidth.' It's an ongoing problem that you're solving every day."

It's not the only problem to solve. Most regions in the US are dominated by one or two major ISPs that are "notorious" for filing frivolous lawsuits against startup Internet providers, according to Don Patten, who has three decades of experience in the business and is now general manager of MINET Fiber in Oregon.

Legal budgets the size of Godzilla

"I have never seen an independent… start up without having to fight the incumbent legally," Patten told Ars. "The incumbents are notorious for frivolous delay lawsuits. They know perfectly well they're frivolous, but it's a delay tactic. They have an army of lawyers and a budget to support lawsuits the size of Godzilla. That's one of their tactics, it always has been. It probably will continue to be so for many years yet to come."That's what happened to fiber ISP Falcon Broadband in Colorado Springs. The company started in 2003, competing against Adelphia, Falcon's former engineering chief Michael Wagner said.

"They did not want anybody else to come into their territory because they wanted to have that monopoly with their franchise agreements," Wagner told Ars. "What they started to do was file frivolous lawsuit after lawsuit to try to basically bankrupt us so we couldn't compete."

Wagner recalled about 10 lawsuits from Adephia, and later Comcast, who took over Adelphia's operations in 2006.

"We've had lawsuits that we were tampering with their equipment; we had lawsuits that we were violating different FCC requirements for the cable plants," he said. "We had lawsuits that we were not honoring different content contractual obligations and that we were doing unfair practices, basically, in the franchising cable agreements."

These kinds attorneys are here to help you lighten the load on your wallet.

Big fiber build outs cost tens of millions of dollars

Building networks is, to no one's surprise, expensive. Financial analysts last year estimated that Google had to spend $84 million to build a fiber network that passed 149,000 homes in Kansas City, with the cost per home at $500 to $674. That figure did not include additional costs for actually connecting each home that requests service. A national Google Fiber build out passing 15 percent of US homes would cost $11 billion a year for five years, Wall Street analysts have estimated.Montgomery discussed the challenge of finding what some people call "patient capital," or investors who are willing to put money into companies that might take five or 10 years to make a big profit.

"Costs are fixed. You're going pay your staff and maintenance people whether you have one customer or 10,000. All your costs are basically going to be the same," he said. "For a fiber network, you need to reach about 30 percent of the local market within a couple of years, or you're going to go out of business."

Montgomery has a few thousand customers between the wireless and fiber businesses, with the University of Kansas' Greek system being his biggest customer base. Montgomery said he buys bandwidth from IP transit provider Hurricane Electric, and he built fiber out to the fraternities and sororities, offering up to a gigabit of bandwidth for $100 a month. "We grow organically, so we've added customers and gradually added bandwidth," he said.

Wicked Broadband started as a nonprofit, but a couple of years ago Montgomery converted it into a for-profit business, which he said made it easier to borrow money.

Wicked Broadband's nonprofit roots are seen in its pledge to provide free Internet access to low-income residents living in Lawrence Housing Authority buildings. Charity can only bring a business so far, though.

"One thing a new Internet service provider can do to leverage bank financing is you can take the long-term projects to the bank and turn them into cash to build the infrastructure," Montgomery said. "So, if you find a customer that is willing to sign a three-year deal, you can walk that to the bank and say, 'hey I need X amount of dollars to pull fiber to this site. Here's the guarantee that we're going to get paid and so can I borrow that money?'"

"One of the really terrible things about being in this business is the infrastructure you're building is very expensive, but it has no collateral value for the bank," Montgomery also said. "If I put $1 million of fiber in the ground and go to the bank, it'll say, 'ok I'm going to need a million dollars' worth of collateral. The fiber isn't worth anything to us, so you're going to have to cough up something else, gold bars, cash, something.'"

Montgomery said he did end up getting about $2 million in funding from "patient" investors. Still, he believes "these networks aren't possible without municipal involvement." Montgomery is seeking a $500,000 grant from the city, but there seems to be a good chance he won't get it: instead of providing the money, the city put out a request for information to seek other companies willing to build a new broadband network.

Montgomery said he's talking to municipal officials in four other communities in Missouri and Kansas about moving to a different market.

"One of the problems with Lawrence is we've never received a single dollar in economic development money, not a single penny," he said. "I love my home town, but it is a very difficult place to do new and innovative things."

Finding customers the easy way

The success Montgomery did have with fraternities and sororities came largely because it was "a segment of the local market that was really underserved," he said.Targeting underserved areas is often the best approach from a business perspective, according to Wagner, who started Falcon Broadband with family. His uncle had been running a construction company that was building infrastructure for big ISPs and eventually decided to create an ISP of his own.

"There was a suburb being built in Colorado Springs that had not yet found a communications company to come there," Wagner said. "Adelphia was hesitant to build out. Qwest hadn't gone in yet. There were probably 500 to 1,000 homes without any communications services, so we decided to make that our head end and from there branch out and try to penetrate into Colorado Springs." Falcon Broadband made money, but "since we were doing so much building of our infrastructure, all the profits were reinvested into the company to keep it building."

Enlarge / Fiber optic cable being laid in Australia.

Falcon started as a wireless Internet service provider, but moved to a fiber-to-the home system to stay competitive after Comcast arrived. By the time Wagner left, he said Falcon was passing 6,000 homes and had customers in about half of those.

"Generally the industry prices itself on getting about 30 percent penetration," so 50 percent was enough to make it worth it. But it would have been a lot harder if Falcon was building out all of its infrastructure in areas already dominated by cable companies.

"If you're already in an area that's being serviced by incumbents, trying to get people to switch over to you can be very challenging," he said. "One [challenge] definitely is building out the infrastructure, getting all the permits to build inside the city. Getting the franchise agreement and the rights to the easement is definitely a roadblock and can be very expensive. The other part is usually companies do all of construction projects when the city is being built. If you're doing an overbuild, the cost goes up even more."

Falcon offers Internet, TV, and phone services, and while Wagner was there the company purchased bandwidth from multiple providers, evaluating them on reliability and price. "We usually had two different sources for that bandwidth, and we would load balance it out, so if there was a problem with routing and pathing, we could easily adjust," he said.

Those annoying channel bundles

Falcon obviously didn't have the content buying power of a major ISP, but like other independent operators, it joined the National Cable Television Cooperative (NCTC), which buys programming on behalf of its members.Wagner doesn't think the current model of Internet providers selling bundles of TV channels is sustainable, but it's hard for small ISPs to break away from offering bundles. While the NCTC creates collective buying power, content companies often demand the carriage of multiple lesser-watched channels before providing access to the most popular ones. Cablevision sued Viacom last year, alleging antitrust violations over this forced bundling.

"It's pretty locked in right now, and they're fighting tooth and nail to keep it that way, but hopefully with services like the Roku box and individualized channels, these companies will start to see that they can still make money by offering only what people want," Wagner said.

While AT&T, Comcast, Verizon, and perhaps others are now seeking payment from transit providers and Web services like Netflix, Wagner doesn't believe in turning the Internet business into a "two-way market," even if it could bring in more money.

"I see Internet service more like a generic utility," he said. "What people do with their bandwidth really is up to them, just like electricity. I'm not going to charge somebody more because they're running an air conditioner as opposed to a ceiling fan. I see the future of the business being more focused on Internet service, and Internet service is going to be the conduit to other types of services that are out there."

A warning to incumbent ISPs

Frustration over incumbent providers has led some municipalities to build their own networks. MINET Fiber was created by the Oregon towns of Monmouth and Independence. The business was registered in 2005, said Marilyn Morton, who serves on the Independence City Council and is an administrator of MINET Fiber."We begged the bigger carriers in the area to bring us at least DSL, and our answer was 'probably by 2016 we can talk,'" she told Ars. "We developed an ISP and fiber optics company because the area was grossly underserved. We were still living in many areas with nothing but dial-up, which means you had to have two phone lines, one so you could answer your phone and one so you could get on your Internet."

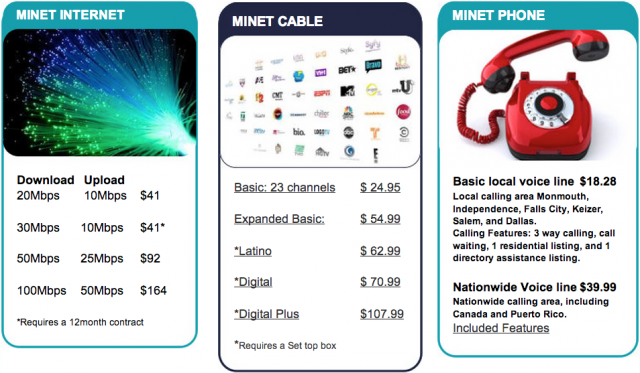

Oregon is one of 30 states that doesn't have laws making it difficult to create municipal broadband networks. MINET's fiber is available to every home and business in Monmouth and Independence, Morton said. Out of 7,500 households, more than half subscribe to at least one of MINET Fiber's triple-play services, Internet, TV, and voice.

Patten, who became GM at MINET Fiber in September 2013, said the ISP didn't initially hit its potential. "The original management of the company was, 'if you build it, they will come,'" he said. "They expected for whatever reason people would just flock through the door. While a municipality tends to have a stronger potential position with their customers than commercial incumbents, you still have to explain to the customer why they should give you the opportunity."

MINET Fiber hasn't started a price war. Instead, the company positions itself as a faster and more reliable provider against competition like CenturyLink and Charter.

Enlarge / MinetFiber prices.

MINET Fiber's revenues already exceed its expenses, not counting debt service. The company is about 18 months away from being able to cover its debt service, as well, without any help from city revenue, Patten said.

Though it took longer than Patten believes it should have to reach profitability, MINET Fiber is an example for other municipalities and perhaps a warning to incumbent ISPs who may be a bit too confident in their hold on customers.

"The same old story just hasn't changed," Patten said. "A lot of communities have gone to their incumbents and offered to financially partner with them, to simply bring their communities up to minimum standards of access, and the incumbents just seem to think they can dictate what you and I, Joe consumer, want. Until they learn, entities such as ourselves will find a way to crop up."

No comments:

Post a Comment