The cops are tracking my car—and yours

My quest to access automatic license plate reader (LPR) records.

Aurich Lawson

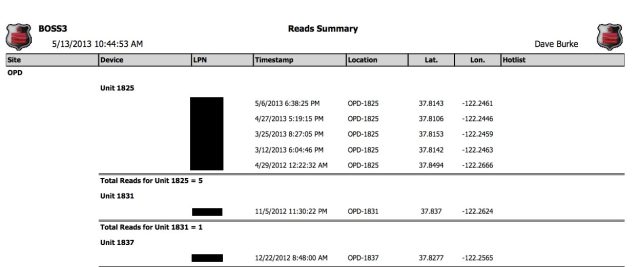

My car was at the corner of Mandana Blvd. and Grand Ave., just blocks away from the apartment that my wife and I moved out of about a month earlier. It’s an intersection I drive through fairly frequently even now, and the OPD’s own license plate reader (LPR) data bears that out. One of its LPRs—Unit 1825—captured my car passing through that intersection twice between late April 2013 and early May 2013.

I have no criminal record, have committed no crime, and am not (as far as I know) under investigation by the OPD or any law enforcement agency. Since I first moved to Oakland in 2005, I’ve been pulled over by the OPD exactly once—for accidentally not making a complete stop while making a right-hand turn at a red light—four years ago. Nevertheless, the OPD’s LPR system captured my car 13 times between April 29, 2012 and May 6, 2013 at various points around the city, and it retained that data. My car is neither wanted nor stolen. The OPD has no warrant on me, no probable cause, and no reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing, yet it watches where I go. Is that a problem?

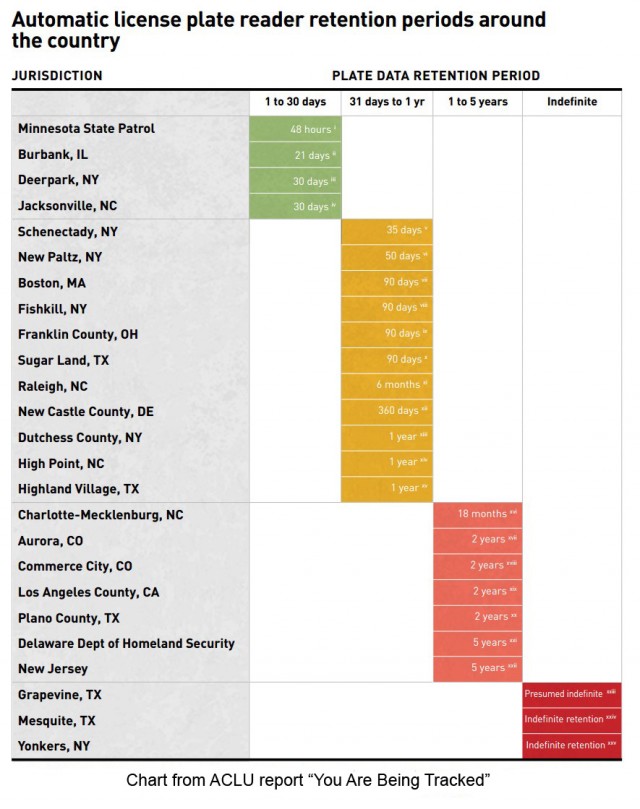

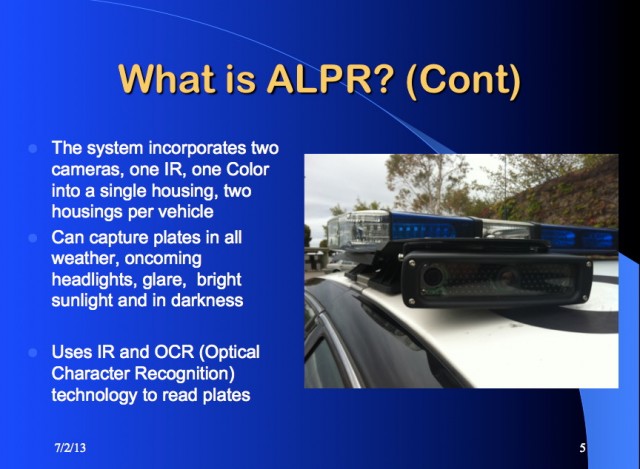

LPR deployments—which are rapidly expanding throughout the country to cities and towns big and small—help law enforcement officers scan license plates extremely quickly (typically, 60 plates per second) and run those against a “hot list” of cars that are wanted or stolen. The cameras themselves can be hidden inside infrastructure or mounted onto squad cars. Law enforcement agencies love them. The federal government is even encouraging local law enforcement (through federal grants) to purchase more for several thousand dollars apiece. But LPRs aren't just looking for stolen cars; they capture every plate that they see. In some cases, they retain that plate, location, date, and time information... indefinitely.

Sid Heal is a recently retired commander who evaluated technology during his decades-long tenure at the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department. He's now a law enforcement consultant and told Ars last year that he's been working with LPRs since 2005.

"It was one of the few technologies that did everything that they said it did as well as they said it did," he said. "It staggered the imagination."

Why does OPD hold records of my car that are more than a year old? Was that data ever accessed by or shared with the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC), a federally funded "fusion center" based in San Francisco? What about other federal agencies? Since asking on July 1, 2013, the OPD has yet to respond to my follow-up questions.

In May 2013, we wrote about a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) against the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD), two of the largest local law enforcement agencies in the country. The plaintiffs asked for “all ALPR data collected or generated between 12:01am on August 12, 2012 and 11:59pm on August 19, 2012, including at a minimum, the license plate number, date, time, and location information for each license plate recorded.”

That case is still pending, but it sparked this idea: why not find out what data exists on my own car? Under the California Public Records Act, I should be able to gain access to my own data—but it turns out that getting information from regional law enforcement agencies is an exercise in both patience and frustration. I’ve spent the last two months trying to track down precisely what LPR data various law enforcement agencies around the San Francisco Bay Area (and a few in Southern California) have captured on my vehicle over the last year. This is uncommon; even here in the Bay Area with its privacy-conscious and tech-savvy users, few people appear to know just how much data the police hold on them. In many cases, I was one of just a few people (and sometimes the only person) to request such data about myself. This is what I found.

See no evil

On May 8, 2013, I submitted a signed letter to the OPD asking for “all data recorded by your agency’s automated license plate reader (ALPR) system between May 6, 2012 and May 6, 2013 for my vehicle, [REDACTED]. This data should include, at a minimum, the license plate number, date, time, and location information.”I submitted similar letters to the neighboring Berkeley Police Department (BPD), the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD), the remaining eight Bay Area county sheriff’s departments, and NCRIC itself. I also made similar requests to the LAPD, LASD, and to my hometown force, the Santa Monica Police Department (SMPD).

Of the 14 agencies I queried, OPD—to its credit—came back with the most substantial dataset. After nearly two months of waiting, it provided a list of 13 data points, many clustered right at an apartment near the Berkeley/Oakland border that my wife and I rented for six weeks in Spring 2012.

View Cyrus Farivar's LPR data (May 2012-May 2013) in a larger map I included the other Southern California entities because my father and brother still live in Santa Monica, and I travel down there a few times per year. The SMPD, with its 11 LPRs, apparently only read my plate once near a freeway onramp that I’ve taken to get to and from my father’s home. (In order to get it, I had to send the SMPD proof of my own car registration—this was the only agency to ask for such documentation.)

The others? Some apparently never saw me at all.

The San Francisco Police Department, with its 24 LPRs, told me by e-mail that my car “was not recorded on our agency’s ALPR system.”

Closer to home, the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office—the county that encompasses Oakland, Berkeley, and a number of other East Bay communities—also said that armed with its seven LPR devices: “we do not have any record of your vehicle.” Our county neighbor to the north, Contra Costa County, apparently didn’t record me either.

Interestingly, some said that they didn’t have any LPR system at all. Santa Clara County (home of Google, Apple, and Yahoo, among other tech giants) told me that its sheriff’s department does not have an LPR system. Neither does Sonoma County, north of the Bay Area.

“This is in response to your request for ALPR data from our agency,” wrote the Napa County Sheriff, home to one of California’s best-known wine regions. “Our agency does not use ALPR readers, therefore we have no data to provide you.”

Solano County, adjacent to Napa County, cryptically told me: “No responsive Sheriff's Office records exist because no information is stored.”

Enlarge / This is a sample of the Oakland Police Department's LPR record on my car.

Cyrus Farivar

Just $1.00 for a worthless photo

The only other Bay Area agency that did have a record of my license plate was the Berkeley Police Department (BPD). Sometime in early June 2013, I got a call from them:“We have two pages of documents for you,” a BPD staffer said. “They cost $0.10 each.”

“And how much if you mail them to me?”

“That’ll be $1.00”

“OK, I’ll just come pick it up.”

Given that I go up to Berkeley—just a few miles away from Oakland—once or twice a week, I thought I could just wait until I was at the BPD headquarters. On a workday, I presented myself at the records window. They asked for $0.20; I handed over a single dollar.

“Sir, you have to have exact change,” a clerk told me.

“OK, then just keep the $0.80.”

I received an envelope with two pages in it. The first page was not typed on any letterhead, addressed to me, or signed by anyone. It simply stated that my car had been read "once by the LPR system," and:

• LPR data is stored on a physically secured server in the city’s data center.The second page was more ridiculous—an enlarged photo of my car and my plate. It provided no information about when or where it was taken.

• Plate read and hit data are retained for one year.

• Authorized police and information technology personnel have exclusive password controlled access to the data using application software.

“I do not believe that the County is the custodian of any records”

As amusing as that $1.00 snapshot is, agencies that out-and-out refused to share any data with me at all were more interesting.Marin County—the county just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco—told me that from June through December of 2012, the county scanned more than 617,000 license plates. What had it achieved by recording all that data? The county sheriff recovered 27 stolen cars.

“Mr. Farivar, we only look up license plates when acting in a law enforcement capacity,” Jerod Kansanback, a deputy at the Marin County Sheriff's Office, wrote in an e-mail to me. “Our policy mandates the License Plate Recognition system is for law enforcement purposes only. As previously stated, we are unable to look up your license plate.”

Immediately south of San Francisco in San Mateo County—home to Facebook—the department was a bit more coy.

“While I do not believe that the County is the custodian of any records responsive to this portion of the request, such documents would not be a public record pursuant to Section 6254(f) of the California Government Code, which exempts from the Public Records Act law enforcement-related documents like them,” wrote David Silberman, the deputy county counsel.

Silberman and I eventually talked on the phone. I found out that he wasn't only working for San Mateo County, but he’s also effectively the only regular attorney for that federally funded “fusion center,” known as the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC).

According to its website:

Per a 2006 presidential directive, the NCRIC serves as the regional "all crimes" intelligence fusion center for the Federal Northern District of California.As Silberman explained it, the NCRIC falls under his current work responsibilities. He works for the San Mateo county counsel’s office but is assigned to the Sheriff’s Office, and the Sheriff’s Office “oversees NCRIC.”

As such, we centralize the intake, analysis, fusion, synthesis, and dissemination of criminal and homeland security intelligence throughout the Northern California coastal counties.

The NCRIC is funded through the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), Department of Homeland Security, Cal EMA, and Bay Area Urban Area Security Initiative (Bay Area UASI).

“I’m the only attorney that provides ongoing advice to NCRIC,” he told Ars, emphasizing that he actually spends very little of his time providing legal services to the agency. “I would be surprised if I spend an hour a month [working for NCRIC].”

So I put it to him: The letter says he doesn’t “believe” that the county has any records of my car. Isn’t there a way to know for sure?

At first, he hemmed and hawed, saying that he couldn’t tell me and again citing that pesky provision, Section 6254(f). If everyone asked for their records, Silberman told me, “it would create a situation [that we couldn’t handle.]”

So how many people had flooded his office with requests similar to mine?

“You’re the second one to ever ask,” he noted, adding that under state statute, law enforcement agencies did not have to provide an individual with such data, but they could do so “voluntarily.” Silberman eventually came around.

“Even though there’s no obligation to do so, I’m going to go ahead and tell you that we have never captured your license plate in San Mateo County,” he said. And NCRIC? “NCRIC has never captured your license plate.”

When I later asked him to confirm the above quote that he told me over the phone in writing, he qualified it this way:

“I do not remember exactly what I learned when I researched a response to your first [Public Records Act request] a while ago, but based on my response, I believe that I probably learned that your license plate was either not captured by a license plate reader owned by the County or the data was purged pursuant to our retention policy (one year),” he wrote.

NCRIC director: “I can't even run my own plate”

The Silberman exchange was a bit confusing, so I eventually spoke with Mike Sena, the director of NCRIC. He explained to me how his agency works.NCRIC has the ability to search LPR databases of other Bay Area law enforcement agencies that choose to share data with it—its members, in turn, have that same ability. But law enforcement agencies are not obligated to share such data. Tiburon in Marin County, for example, famously has LPRs mounted above the only two roads going in and out of town. It chooses not to share its data with NCRIC.

Sena told Ars that when NCRIC runs a plate search, it's restricted to just one year of data—even if a local agency retains it for longer than that period. Further, officers aren't supposed to search the LPR database willy-nilly.

"I can't even run my own plate," he said. "The system is set up [such that officers need] to have a lawful purpose and reason. If the officer doesn't have that lawful purpose, he can't do a search on the system. [That would entail] a criminal violation or something that merits access to the system. We've restricted it to only those who have the need and the right to know."

In the eight months since NCRIC's data sharing system—including its own six LPRs—has come online, no one has been punished for accessing the LPR database when they shouldn't have.

Sena added that when a federal law enforcement agency wants to investigate a particular plate, they'd likely come to NCRIC first to conduct a search. The NCRIC would essentially act as a middleman between local and federal authorities. But if NCRIC didn't have access to a record older than a year, the feds would likely double check with an individual agency directly because they may still have some older records.

Still, NCRIC's director called himself a "big privacy advocate."

"I've been part of civil rights and civil liberties organizations since I was in high school," he added. "That's why I'm a member of the ACLU. But what does privacy mean? Is it private to be in a public place and drive your car? What are the expectations? It becomes more difficult with how much freedom you have in public. What do folks define their privacy as?"

Sena argued that LPR data is a "useful tool," citing the example of the 1997 kidnapping and murder of Anthony Martinez, a Southern California boy. It's a case that Sena worked on directly. Martinez' now-convicted murderer, Joseph Duncan, was later caught in Idaho after having killed again.

"We had a partial plate, but we were never able to figure it out at the time," Sena said. "The individual that killed [Martinez] went on to kill many more people. If we had been able to have the ALPR data when Anthony was kidnapped—we may not have been able to save Anthony, but [maybe] the rest of the people—it still bothers me. We would have been able to stop that whole chain of murders."

The director also said that annually, the NCRIC has access to "10,000 hits that are based off of stolen vehicles, subjects under investigation." Once a plate is part of a local, state, or federal investigation, that one-year retention period gets bumped up to five years.

And how many more license plate records does NCRIC have access to, that like mine, presumably are not under investigation? Sena said he'd get back to me. By July 15, the agency's privacy officer, Hugh Cotton, responded by e-mail that this was "a metric not tracked by the NCRIC and therefore I am not able to provide an answer responsive to this particular request."

The exemptions

Like San Mateo County, the LASD and the LAPD both cited the Public Records Act Section 6254—subsection f and k, respectively—as to why they could not provide me with data on my license plate.So what do those sections of California state law say, anyway? They outline a list of exceptions to what public agencies must disclose, including:

Subsection f:It’s a bit hard to understand how as a law-abiding citizen, asking for my own data constitutes either an “investigation,” a “record of intelligence information or security procedure,” or an “investigatory or security file.” After all, I wasn’t asking these law enforcement agencies to disclose where the cameras are or how they can be defeated. I didn't want records on cases that I knew were currently being investigated. I wasn’t even asking these agencies for a substantial quantity of data—I merely wanted my own. And some other law enforcement agencies didn’t have a problem handing it over.

Records of complaints to, or investigations conducted by, or records of intelligence information or security procedures of, the office of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice, the California Emergency Management Agency, and any state or local police agency, or any investigatory or security files compiled by any other state or local police agency, or any investigatory or security files compiled by any other state or local agency for correctional, law enforcement, or licensing purposes.

Subsection k:

Records, the disclosure of which is exempted or prohibited pursuant to federal or state law, including, but not limited to, provisions of the Evidence Code relating to privilege.

If this was the European Union, it would be an open-and-shut case. There, citizens have the right to request all the data any company or government agency has about a person, and the organization must comply. American law has no equivalent principle, largely leaving privacy and data protection issues to be sorted out in contract law between individuals, corporations, and states. The European Union concept here is summed up in Section V, Article 12 of the 1995 EU directive "On the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data."

California case law has its own record on the subject. Back in 1971, a California appellate court found, in the case of Uribe v. Howie, the federal analog to the state’s Public Records Act, known as the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The court noted that “investigatory files” can only exist when the “prospect of enforcement proceedings is concrete and definite. It is not enough that an agency label its file ‘investigatory’ and suggest that enforcement proceedings may be initiated at some unspecified future date or were previously considered.”

The court added:

In their course of activities the regulatory agencies of this state accumulate numerous records which may, under certain circumstances, be used in disciplinary proceedings. Virtually any record so kept could be put to such use. To say that the exemption created by subdivision (f) is applicable to any document which a public agency might, under any circumstances, use in the course of a disciplinary proceeding would be to create a virtual carte blanche for the denial of public access to public records. The exception would thus swallow the rule. This could not have been the intent of the Legislature.

Similarly, in a 1982 case, American Civil Liberties Union Foundation v. Deukmejian, the Supreme Court of California agreed with this line of reasoning:

We therefore reject defendants' contention that the "intelligence information" exemption of section 6254, subdivision (f), exempts all information which is "reasonably related to criminal activity." Such a broad exemption would in essence resurrect the federal judicial doctrine which Congress repudiated in 1974, and which was never part of California law. It would undercut the California decisions which in some circumstances limit the exemption of subdivision (f) to cases involving concrete and definite enforcement prospects. And most important, it would effectively exclude the law enforcement function of state and local governments from any public scrutiny under the California Act, a result inconsistent with its fundamental purpose.In a more recent case (Haynie v. Superior Court) from 2001, a California appellate court again found that law enforcement agencies could not summarily restrict access.

Yet, by including "routine" and "everyday" within the ambit of "investigations" in section 6254(f), we do not mean to shield everything law enforcement officers do from disclosure. (Cf. ACLU, supra, 32 Cal.3d at p. 449.) Often, officers make inquiries of citizens for purposes related to crime prevention and public safety that are unrelated to either civil or criminal investigations. The records of investigation exempted under section 6254(f) encompass only those investigations undertaken for the purpose of determining whether a violation of law may occur or has occurred.Armed with those decisions on my side and some well-paid lawyers, I probably could make a compelling case to challenge those law enforcement agencies that denied me. But that would involve suing them, likely to the tune of several thousand dollars or more. I don't have that kind of money to spend on lawsuits.

So I asked Sena: should individual citizens, like me, have the right to access LPR data about themselves?

First, he said, it's far too difficult to "verify, validate, or vet" whether a person is the actual owner. But second, he curiously cited reasons of privacy.

"You don't know who is in the car," he told Ars. "What if you want to know where [your] wife has been? This jeopardizes the privacy of the individuals who may be in the vehicle. Maybe you loaned out your car, and you know who you loaned it to. I think it causes way too many problems of individuals tracking other individuals."

This, of course, is precisely what law enforcement agencies are doing already.

Enlarge /

The San Leandro Police Department captured this photo of Mike

Katz-Lacabe and his daughters in front of their home on November 14,

2009.

“Everybody has something to hide”

While reporting, I also met with Mike Katz-Lacabe, a member of the school board in San Leandro (the city immediately to the south of Oakland). He’s been mentioned numerous times in the local and national media for having requested and received license plate reader data about himself.One such photo, which garners mention more than any of the others, shows him and his daughters exiting his car in front of his home.

As an individual citizen, Katz-Lacabe has queried all 90 city and county law enforcement agencies across the entire San Francisco Bay Area, looking specifically for policies, purchase orders, memoranda of understanding, and other documents—he calls it “going down a rabbit hole.”

But it was only in his home city, San Leandro, where he’s requested the actual LPR data—all 112 records collected over two years. The city partially obliged, surrendering dates, times, and photographs—but not locations.

“They didn’t send the GPS location data,” he told Ars. “[The San Leandro Police Department] wanted $5 per record. With 112 records, that’s $560.”

It turns out Katz-Lacabe is the only other citizen that San Mateo County and NCRIC have received a request from concerning LPR data—he currently has a new query pending with the agency. He recently sent a request to the San Leandro Police Department and to NCRIC itself, asking for "all data gathered by the ALPRs of the two vehicles that I own and are registered in my name."

“I want to find out more about NCRIC. How long do they retain data? Who else are they sharing it with? What else is it used for?” he told me over coffee.

“My problem with this whole thing is not LPR in general; it's a way for an officer to do things faster and more thoroughly than they did before. Now, if they flag a stolen car, it beeps and gives a visual alert on the screen. I think all that's fine. The problem is that most of the information, 99.5 percent of the information they gather is information of people that are not suspected of nor charged with any crime. Now we have law enforcement gathering information on innocent people that can be used in other ways. [Is it used] to develop probable cause, or could it be used for other things? Are you a customer of a medical marijuana dispensary? Do you go to church on Sundays? Are you an attractive woman that I want to find out where [you] frequent? People say ‘I have nothing to hide’—but everybody has something to hide.”

No comments:

Post a Comment