How the CIA made Google

Inside the secret network behind mass surveillance, endless war, and Skynet—

part 1

INSURGE INTELLIGENCE,

a new crowd-funded investigative journalism project, breaks the

exclusive story of how the United States intelligence community funded,

nurtured and incubated Google as part of a drive to dominate the world

through control of information. Seed-funded by the NSA and CIA, Google

was merely the first among a plethora of private sector start-ups

co-opted by US intelligence to retain ‘information superiority.’

The

origins of this ingenious strategy trace back to a secret

Pentagon-sponsored group, that for the last two decades has functioned

as a bridge between the US government and elites across the business,

industry, finance, corporate, and media sectors. The group has allowed

some of the most powerful special interests in corporate America to

systematically circumvent democratic accountability and the rule of law

to influence government policies, as well as public opinion in the US

and around the world. The results have been catastrophic: NSA mass

surveillance, a permanent state of global war, and a new initiative to

transform the US military into Skynet.

THIS IS PART ONE. READ PART TWO HERE.

This

exclusive is being released for free in the public interest, and was

enabled by crowdfunding. I’d like to thank my amazing community of

patrons for their support, which gave me the opportunity to work on this

in-depth investigation. Please support independent, investigative journalism for the global commons.

In

the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, western governments are

moving fast to legitimize expanded powers of mass surveillance and

controls on the internet, all in the name of fighting terrorism.

US and European politicians

have called to protect NSA-style snooping, and to advance the capacity

to intrude on internet privacy by outlawing encryption. One idea is to

establish a telecoms partnership that would unilaterally delete content

deemed to “fuel hatred and violence” in situations considered

“appropriate.” Heated discussions are going on at government and

parliamentary level to explore cracking down on lawyer-client confidentiality.

What any of this would have done to prevent the Charlie Hebdo attacks remains a mystery, especially given that we already know the terrorists were on the radar of French intelligence for up to a decade.

There

is little new in this story. The 9/11 atrocity was the first of many

terrorist attacks, each succeeded by the dramatic extension of draconian

state powers at the expense of civil liberties, backed up with the

projection of military force in regions identified as hotspots

harbouring terrorists. Yet there is little indication that this tried

and tested formula has done anything to reduce the danger. If anything,

we appear to be locked into a deepening cycle of violence with no clear

end in sight.

As our governments push to increase their powers, INSURGE INTELLIGENCE can

now reveal the vast extent to which the US intelligence community is

implicated in nurturing the web platforms we know today, for the precise

purpose of utilizing the technology as a mechanism to fight global

‘information war’ — a war to legitimize the power of the few over the

rest of us. The lynchpin of this story is the corporation that in many

ways defines the 21st century with its unobtrusive omnipresence: Google.

Google

styles itself as a friendly, funky, user-friendly tech firm that rose

to prominence through a combination of skill, luck, and genuine

innovation. This is true. But it is a mere fragment of the story. In

reality, Google is a smokescreen behind which lurks the US

military-industrial complex.

The

inside story of Google’s rise, revealed here for the first time, opens a

can of worms that goes far beyond Google, unexpectedly shining a light

on the existence of a parasitical network driving the evolution of the

US national security apparatus, and profiting obscenely from its

operation.

The shadow network

For

the last two decades, US foreign and intelligence strategies have

resulted in a global ‘war on terror’ consisting of prolonged military

invasions in the Muslim world and comprehensive surveillance of civilian

populations. These strategies have been incubated, if not dictated, by a

secret network inside and beyond the Pentagon.

Established

under the Clinton administration, consolidated under Bush, and firmly

entrenched under Obama, this bipartisan network of mostly

neoconservative ideologues sealed its dominion inside the US Department

of Defense (DoD) by the dawn of 2015, through the operation of an

obscure corporate entity outside the Pentagon, but run by the Pentagon.

In

1999, the CIA created its own venture capital investment firm,

In-Q-Tel, to fund promising start-ups that might create technologies

useful for intelligence agencies. But the inspiration for In-Q-Tel came

earlier, when the Pentagon set up its own private sector outfit.

Known

as the ‘Highlands Forum,’ this private network has operated as a bridge

between the Pentagon and powerful American elites outside the military

since the mid-1990s. Despite changes in civilian administrations, the

network around the Highlands Forum has become increasingly successful in

dominating US defense policy.

Giant

defense contractors like Booz Allen Hamilton and Science Applications

International Corporation are sometimes referred to as the ‘shadow

intelligence community’ due to the revolving doors between them and

government, and their capacity to simultaneously influence and profit

from defense policy. But while these contractors compete for power and

money, they also collaborate where it counts. The Highlands Forum has

for 20 years provided an off the record space for some of the most

prominent members of the shadow intelligence community to convene with

senior US government officials, alongside other leaders in relevant

industries.

I first stumbled upon the existence of this network in November 2014, when I reported for VICE’s Motherboard that US defense secretary Chuck Hagel’s newly announced ‘Defense Innovation Initiative’ was really about building Skynet — or something like it, essentially to dominate an emerging era of automated robotic warfare.

That

story was based on a little-known Pentagon-funded ‘white paper’

published two months earlier by the National Defense University (NDU) in

Washington DC, a leading US military-run institution that, among other

things, generates research to develop US defense policy at the highest

levels. The white paper clarified the thinking behind the new

initiative, and the revolutionary scientific and technological

developments it hoped to capitalize on.

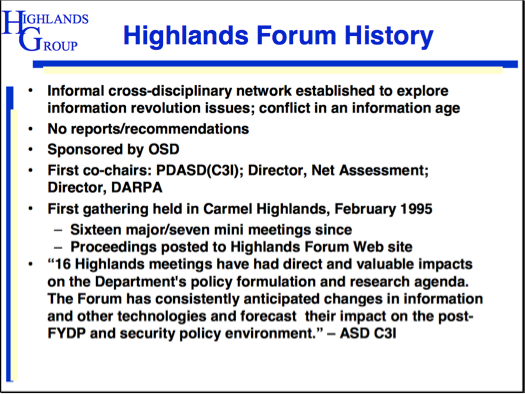

The Highlands Forum

The

co-author of that NDU white paper is Linton Wells, a 51-year veteran US

defense official who served in the Bush administration as the

Pentagon’s chief information officer, overseeing the National Security

Agency (NSA) and other spy agencies. He still holds active top-secret security clearances, and according to a report by Government Executive magazine in 2006 he chaired the ‘Highlands Forum’, founded by the Pentagon in 1994.

New Scientist magazine

(paywall) has compared the Highlands Forum to elite meetings like

“Davos, Ditchley and Aspen,” describing it as “far less well known, yet…

arguably just as influential a talking shop.” Regular Forum meetings

bring together “innovative people to consider interactions between

policy and technology. Its biggest successes have been in the

development of high-tech network-based warfare.”

Given

Wells’ role in such a Forum, perhaps it was not surprising that his

defense transformation white paper was able to have such a profound

impact on actual Pentagon policy. But if that was the case, why had no

one noticed?

Despite being

sponsored by the Pentagon, I could find no official page on the DoD

website about the Forum. Active and former US military and intelligence

sources had never heard of it, and neither did national security

journalists. I was baffled.

The Pentagon’s intellectual capital venture firm

In the prologue to his 2007 book, A Crowd of One: The Future of Individual Identity,

John Clippinger, an MIT scientist of the Media Lab Human Dynamics

Group, described how he participated in a “Highlands Forum” gathering,

an “invitation-only meeting funded by the Department of Defense and

chaired by the assistant for networks and information integration.” This

was a senior DoD post overseeing operations and policies for the

Pentagon’s most powerful spy agencies including the NSA, the Defense

Intelligence Agency (DIA), among others. Starting from 2003, the

position was transitioned into what is now the undersecretary of defense

for intelligence. The Highlands Forum, Clippinger wrote, was founded by

a retired US Navy captain named Dick O’Neill. Delegates include senior

US military officials across numerous agencies and

divisions — “captains, rear admirals, generals, colonels, majors and

commanders” as well as “members of the DoD leadership.”

What at first appeared to be the Forum’s main website

describes Highlands as “an informal cross-disciplinary network

sponsored by Federal Government,” focusing on “information, science and

technology.” Explanation is sparse, beyond a single ‘Department of

Defense’ logo.

But Highlands also has another

website describing itself as an “intellectual capital venture firm”

with “extensive experience assisting corporations, organizations, and

government leaders.” The firm provides a “wide range of services,

including: strategic planning, scenario creation and gaming for

expanding global markets,” as well as “working with clients to build

strategies for execution.” ‘The Highlands Group Inc.,’ the website says,

organizes a whole range of Forums on these issue.

For

instance, in addition to the Highlands Forum, since 9/11 the Group runs

the ‘Island Forum,’ an international event held in association with

Singapore’s Ministry of Defense, which O’Neill oversees as “lead

consultant.” The Singapore Ministry of Defense website describes the

Island Forum as “patterned after

the Highlands Forum organized for the US Department of Defense.”

Documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden confirmed that

Singapore played a key role in permitting the US and Australia to tap undersea cables to spy on Asian powers like Indonesia and Malaysia.

The

Highlands Group website also reveals that Highlands is partnered with

one of the most powerful defense contractors in the United States.

Highlands is “supported by a network of companies and independent

researchers,” including “our Highlands Forum partners for the past ten

years at SAIC; and the vast Highlands network of participants in the

Highlands Forum.”

SAIC

stands for the US defense firm, Science Applications International

Corporation, which changed its name to Leidos in 2013, operating SAIC as

a subsidiary. SAIC/Leidos is among the top 10

largest defense contractors in the US, and works closely with the US

intelligence community, especially the NSA. According to investigative

journalist Tim Shorrock, the first to disclose the vast extent of the

privatization of US intelligence with his seminal book Spies for Hire,

SAIC has a “symbiotic relationship with the NSA: the agency is the

company’s largest single customer and SAIC is the NSA’s largest

contractor.”

The

full name of Captain “Dick” O’Neill, the founding president of the

Highlands Forum, is Richard Patrick O’Neill, who after his work in the

Navy joined the DoD. He served his last post as deputy for strategy and

policy in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Defense for Command,

Control, Communications and Intelligence, before setting up Highlands.

The Club of Yoda

But Clippinger also referred to another mysterious individual revered by Forum attendees:

“He sat at the back of the room, expressionless behind thick, black-rimmed glasses. I never heard him utter a word… Andrew (Andy) Marshall is an icon within DoD. Some call him Yoda, indicative of his mythical inscrutable status… He had served many administrations and was widely regarded as above partisan politics. He was a supporter of the Highlands Forum and a regular fixture from its beginning.”

Since

1973, Marshall has headed up one of the Pentagon’s most powerful

agencies, the Office of Net Assessment (ONA), the US defense secretary’s

internal ‘think tank’ which conducts highly classified research on

future planning for defense policy across the US military and

intelligence community. The ONA has played a key role in major Pentagon

strategy initiatives, including Maritime Strategy, the Strategic Defense

Initiative, the Competitive Strategies Initiative, and the Revolution

in Military Affairs.

In a rare 2002 profile in Wired,

reporter Douglas McGray described Andrew Marshall, now 93 years old, as

“the DoD’s most elusive” but “one of its most influential” officials.

McGray added that “Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald

Rumsfeld, and Deputy Secretary Paul Wolfowitz” — widely considered the

hawks of the neoconservative movement in American politics — were among

Marshall’s “star protégés.”

Speaking at a low-key Harvard University seminar

a few months after 9/11, Highlands Forum founding president Richard

O’Neill said that Marshall was much more than a “regular fixture” at the

Forum. “Andy Marshall is our co-chair, so indirectly everything that we

do goes back into Andy’s system,” he told the audience. “Directly,

people who are in the Forum meetings may be going back to give briefings

to Andy on a variety of topics and to synthesize things.” He also said

that the Forum had a third co-chair: the director of the Defense Advanced Research and Projects Agency (DARPA),

which at that time was a Rumsfeld appointee, Anthony J. Tether. Before

joining DARPA, Tether was vice president of SAIC’s Advanced Technology

Sector.

The

Highlands Forum’s influence on US defense policy has thus operated

through three main channels: its sponsorship by the Office of the

Secretary of Defense (around the middle of last decade this was

transitioned specifically to the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence,

which is in charge of the main surveillance agencies); its direct link

to Andrew ‘Yoda’ Marshall’s ONA; and its direct link to DARPA.

The

Highlands Forum’s influence on US defense policy has thus operated

through three main channels: its sponsorship by the Office of the

Secretary of Defense (around the middle of last decade this was

transitioned specifically to the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence,

which is in charge of the main surveillance agencies); its direct link

to Andrew ‘Yoda’ Marshall’s ONA; and its direct link to DARPA.

According to Clippinger in A Crowd of One,

“what happens at informal gatherings such as the Highlands Forum could,

over time and through unforeseen curious paths of influence, have

enormous impact, not just within the DoD but throughout the world.” He

wrote that the Forum’s ideas have “moved from being heretical to

mainstream. Ideas that were anathema in 1999 had been adopted as policy

just three years later.”

Although

the Forum does not produce “consensus recommendations,” its impact is

deeper than a traditional government advisory committee. “The ideas that

emerge from meetings are available for use by decision-makers as well

as by people from the think tanks,” according to O’Neill:

“We’ll include people from Booz, SAIC, RAND, or others at our meetings… We welcome that kind of cooperation, because, truthfully, they have the gravitas. They are there for the long haul and are able to influence government policies with real scholarly work… We produce ideas and interaction and networks for these people to take and use as they need them.”

My repeated

requests to O’Neill for information on his work at the Highlands Forum

were ignored. The Department of Defense also did not respond to multiple

requests for information and comment on the Forum.

Information warfare

The

Highlands Forum has served as a two-way ‘influence bridge’: on the one

hand, for the shadow network of private contractors to influence the

formulation of information operations policy across US military

intelligence; and on the other, for the Pentagon to influence what is

going on in the private sector. There is no clearer evidence of this

than the truly instrumental role of the Forum in incubating the idea of

mass surveillance as a mechanism to dominate information on a global

scale.

In 1989, Richard O’Neill, then a US Navy cryptologist, wrote a paper for the US Naval War College, ‘Toward a methodology for perception management.’ In his book, Future Wars,

Col. John Alexander, then a senior officer in the US Army’s

Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM), records that O’Neill’s paper

for the first time outlined a strategy for “perception management” as

part of information warfare (IW). O’Neill’s proposed strategy identified

three categories of targets for IW: adversaries, so they believe they

are vulnerable; potential partners, “so they perceive the cause [of war]

as just”; and finally, civilian populations and the political

leadership so they “perceive the cost as worth the effort.” A secret

briefing based on O’Neill’s work “made its way to the top leadership” at

DoD. “They acknowledged that O’Neill was right and told him to bury it.

Except the DoD didn’t bury it. Around 1994,

the Highlands Group was founded by O’Neill as an official Pentagon

project at the appointment of Bill Clinton’s then defense secretary William Perry — who went on to join SAIC’s board of directors after retiring from government in 2003.

In O’Neill’s own words, the group would function as the Pentagon’s ‘ideas lab’. According to Government Executive,

military and information technology experts gathered at the first Forum

meeting “to consider the impacts of IT and globalization on the United

States and on warfare. How would the Internet and other emerging

technologies change the world?” The meeting helped plant the idea of

“network-centric warfare” in the minds of “the nation’s top military

thinkers.”

Excluding the public

Official

Pentagon records confirm that the Highlands Forum’s primary goal was to

support DoD policies on O’Neill’s specialism: information warfare.

According to the Pentagon’s 1997 Annual Report to the President and the Congress under

a section titled ‘Information Operations,’ (IO) the Office of the

Secretary of Defense (OSD) had authorized the “establishment of the

Highlands Group of key DoD, industry, and academic IO experts” to

coordinate IO across federal military intelligence agencies.

The following year’s DoD annual report

reiterated the Forum’s centrality to information operations: “To

examine IO issues, DoD sponsors the Highlands Forum, which brings

together government, industry, and academic professionals from various

fields.”

Notice that in

1998, the Highlands ‘Group’ became a ‘Forum.’ According to O’Neill, this

was to avoid subjecting Highlands Forums meetings to “bureaucratic

restrictions.” What he was alluding to was the Federal Advisory

Committee Act (FACA), which regulates the way the US government can

formally solicit the advice of special interests.

Known

as the ‘open government’ law, FACA requires that US government

officials cannot hold closed-door or secret consultations with people

outside government to develop policy. All such consultations should take

place via federal advisory committees that permit public scrutiny. FACA

requires that meetings be held in public, announced via the Federal

Register, that advisory groups are registered with an office at the

General Services Administration, among other requirements intended to

maintain accountability to the public interest.

But Government Executive reported

that “O’Neill and others believed” such regulatory issues “would quell

the free flow of ideas and no-holds-barred discussions they sought.”

Pentagon lawyers had warned that the word ‘group’ might necessitate

certain obligations and advised running the whole thing privately: “So

O’Neill renamed it the Highlands Forum and moved into the private sector

to manage it as a consultant to the Pentagon.” The Pentagon Highlands

Forum thus runs under the mantle of O’Neill’s ‘intellectual capital

venture firm,’ ‘Highlands Group Inc.’

In

1995, a year after William Perry appointed O’Neill to head up the

Highlands Forum, SAIC — the Forum’s “partner” organization — launched

a new Center for Information Strategy and Policy under the direction of

“Jeffrey Cooper, a member of the Highlands Group who advises senior

Defense Department officials on information warfare issues.” The Center

had precisely the same objective as the Forum, to function as “a

clearinghouse to bring together the best and brightest minds in

information warfare by sponsoring a continuing series of seminars,

papers and symposia which explore the implications of information

warfare in depth.” The aim was to “enable leaders and policymakers from

government, industry, and academia to address key issues surrounding

information warfare to ensure that the United States retains its edge

over any and all potential enemies.”

Despite FACA regulations, federal advisory committees are already heavily influenced, if not captured, by corporate power.

So in bypassing FACA, the Pentagon overrode even the loose restrictions

of FACA, by permanently excluding any possibility of public engagement.

O’Neill’s

claim that there are no reports or recommendations is disingenuous. By

his own admission, the secret Pentagon consultations with industry that

have taken place through the Highlands Forum since 1994 have been

accompanied by regular presentations of academic and policy papers,

recordings and notes of meetings, and other forms of documentation that

are locked behind a login only accessible by Forum delegates. This

violates the spirit, if not the letter, of FACA — in a way that is

patently intended to circumvent democratic accountability and the rule

of law.

The Highlands Forum

doesn’t need to produce consensus recommendations. Its purpose is to

provide the Pentagon a shadow social networking mechanism to cement

lasting relationships with corporate power, and to identify new talent,

that can be used to fine-tune information warfare strategies in absolute

secrecy.

Total participants

in the DoD’s Highlands Forum number over a thousand, although sessions

largely consist of small closed workshop style gatherings of maximum

25–30 people, bringing together experts and officials depending on the

subject. Delegates have included senior personnel from SAIC and Booz

Allen Hamilton, RAND Corp., Cisco, Human Genome Sciences, eBay, PayPal,

IBM, Google, Microsoft, AT&T, the BBC, Disney, General Electric,

Enron, among innumerable others; Democrat and Republican members of

Congress and the Senate; senior executives from the US energy industry

such as Daniel Yergin of IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates; and

key people involved in both sides of presidential campaigns.

Other participants have included senior media professionals: David Ignatius, associate editor of the Washington Post and at the time the executive editor of the International Herald Tribune; Thomas Friedman, long-time New York Times columnist; Arnaud de Borchgrave, an editor at Washington Times and United Press International; Steven Levy, a former Newsweek editor, senior writer for Wired and now chief tech editor at Medium; Lawrence Wright, staff writer at the New Yorker; Noah Shachtmann, executive editor at the Daily Beast; Rebecca McKinnon, co-founder of Global Voices Online; Nik Gowing of the BBC; and John Markoff of the New York Times.

Due

to its current sponsorship by the OSD’s undersecretary of defense for

intelligence, the Forum has inside access to the chiefs of the main US

surveillance and reconnaissance agencies, as well as the directors and

their assistants at DoD research agencies, from DARPA, to the ONA. This

also means that the Forum is deeply plugged into the Pentagon’s policy

research task forces.

Google: seeded by the Pentagon

In

1994 — the same year the Highlands Forum was founded under the

stewardship of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the ONA, and

DARPA — two young PhD students at Stanford University, Sergey Brin and

Larry Page, made their breakthrough on the first automated web crawling

and page ranking application. That application remains the core

component of what eventually became Google’s search service. Brin and

Page had performed their work with funding from the Digital Library Initiative (DLI), a multi-agency programme of the National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA and DARPA.

But that’s just one side of the story.

Throughout

the development of the search engine, Sergey Brin reported regularly

and directly to two people who were not Stanford faculty at all: Dr.

Bhavani Thuraisingham and Dr. Rick Steinheiser. Both were

representatives of a sensitive US intelligence community research

programme on information security and data-mining.

Thuraisingham

is currently the Louis A. Beecherl distinguished professor and

executive director of the Cyber Security Research Institute at the

University of Texas, Dallas, and a sought-after expert on data-mining,

data management and information security issues. But in the 1990s, she

worked for the MITRE Corp., a leading US defense contractor, where she

managed the Massive Digital Data Systems initiative, a project sponsored

by the NSA, CIA, and the Director of Central Intelligence, to foster

innovative research in information technology.

“We

funded Stanford University through the computer scientist Jeffrey

Ullman, who had several promising graduate students working on many

exciting areas,” Prof. Thuraisingham told me. “One of them was Sergey

Brin, the founder of Google. The intelligence community’s MDDS program

essentially provided Brin seed-funding, which was supplemented by many

other sources, including the private sector.”

This

sort of funding is certainly not unusual, and Sergey Brin’s being able

to receive it by being a graduate student at Stanford appears to have

been incidental. The Pentagon was all over computer science research at

this time. But it illustrates how deeply entrenched the culture of

Silicon Valley is in the values of the US intelligence community.

In an extraordinary document

hosted by the website of the University of Texas, Thuraisingham

recounts that from 1993 to 1999, “the Intelligence Community [IC]

started a program called Massive Digital Data Systems (MDDS) that I was

managing for the Intelligence Community when I was at the MITRE

Corporation.” The program funded 15 research efforts at various

universities, including Stanford. Its goal was developing “data

management technologies to manage several terabytes to petabytes of

data,” including for “query processing, transaction management, metadata

management, storage management, and data integration.”

At

the time, Thuraisingham was chief scientist for data and information

management at MITRE, where she led team research and development efforts

for the NSA, CIA, US Air Force Research Laboratory, as well as the US

Army’s Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR) and

Communications and Electronic Command (CECOM). She went on to teach

courses for US government officials and defense contractors on

data-mining in counter-terrorism.

In

her University of Texas article, she attaches the copy of an abstract

of the US intelligence community’s MDDS program that had been presented

to the “Annual Intelligence Community Symposium” in 1995. The abstract

reveals that the primary sponsors of the MDDS programme were three

agencies: the NSA, the CIA’s Office of Research & Development, and

the intelligence community’s Community Management Staff (CMS) which

operates under the Director of Central Intelligence. Administrators of

the program, which provided funding of around 3–4 million dollars per

year for 3–4 years, were identified as Hal Curran (NSA), Robert Kluttz

(CMS), Dr. Claudia Pierce (NSA), Dr. Rick Steinheiser (ORD — standing

for the CIA’s Office of Research and Devepment), and Dr. Thuraisingham

herself.

Thuraisingham goes

on in her article to reiterate that this joint CIA-NSA program partly

funded Sergey Brin to develop the core of Google, through a grant to

Stanford managed by Brin’s supervisor Prof. Jeffrey D. Ullman:

“In fact, the Google founder Mr. Sergey Brin was partly funded by this program while he was a PhD student at Stanford. He together with his advisor Prof. Jeffrey Ullman and my colleague at MITRE, Dr. Chris Clifton [Mitre’s chief scientist in IT], developed the Query Flocks System which produced solutions for mining large amounts of data stored in databases. I remember visiting Stanford with Dr. Rick Steinheiser from the Intelligence Community and Mr. Brin would rush in on roller blades, give his presentation and rush out. In fact the last time we met in September 1998, Mr. Brin demonstrated to us his search engine which became Google soon after.”

Brin

and Page officially incorporated Google as a company in September 1998,

the very month they last reported to Thuraisingham and Steinheiser.

‘Query Flocks’ was also part of Google’s patented ‘PageRank’

search system, which Brin developed at Stanford under the CIA-NSA-MDDS

programme, as well as with funding from the NSF, IBM and Hitachi. That

year, MITRE’s Dr. Chris Clifton, who worked under Thuraisingham to

develop the ‘Query Flocks’ system, co-authored a paper with Brin’s

superviser, Prof. Ullman, and the CIA’s Rick Steinheiser. Titled

‘Knowledge Discovery in Text,’ the paper was presented at an academic conference.

“The

MDDS funding that supported Brin was significant as far as seed-funding

goes, but it was probably outweighed by the other funding streams,”

said Thuraisingham. “The duration of Brin’s funding was around two years

or so. In that period, I and my colleagues from the MDDS would visit

Stanford to see Brin and monitor his progress every three months or so.

We didn’t supervise exactly, but we did want to check progress, point

out potential problems and suggest ideas. In those briefings, Brin did

present to us on the query flocks research, and also demonstrated to us

versions of the Google search engine.”

Brin

thus reported to Thuraisingham and Steinheiser regularly about his work

developing Google. The MDDS programme is actually referenced in several

papers co-authored by Brin and Page while at Stanford. In their 1998 paper published in the Bulletin of the IEEE Computer Society Technical Committeee on Data Engineering,

they describe the automation of methods to extract information from the

web via “Dual Iterative Pattern Relation Extraction,” the development

of “a global ranking of Web pages called PageRank,” and the use of

PageRank “to develop a novel search engine called Google.” Through an

opening footnote, Sergey Brin confirms he was “Partially supported by

the Community Management Staff’s Massive Digital Data Systems Program,”

through an NSF grant — confirming that the CIA-NSA-MDDS program provided

its funding through the NSF.

This grant, whose project report lists Brin

among the students supported (without mentioning the MDDS), was

different to the NSF grant to Larry Page that included funding from

DARPA and NASA. The project report, authored by Brin’s supervisor Prof.

Ullman, goes on to say under the section ‘Indications of Success’ that

“there are some new stories of startups based on NSF-supported

research.” Under ‘Project Impact,’ the report remarks: “Finally, the

google project has also gone commercial as Google.com.”

Thuraisingham’s

account therefore demonstrates that the CIA-NSA-MDDS program was not

only funding Brin throughout his work with Larry Page developing Google,

but that senior US intelligence representatives including a CIA

official oversaw the evolution of Google in this pre-launch phase, all

the way until the company was ready to be officially founded. Google,

then, had been enabled with a “significant” amount of seed-funding and

oversight from the Pentagon: namely, the CIA, NSA, and DARPA.

The DoD could not be reached for comment.

When

I asked Prof. Ullman to confirm whether or not Brin was partly funded

under the intelligence community’s MDDS program, and whether Ullman was

aware that Brin was regularly briefing the CIA’s Rick Steinheiser on his

progress in developing the Google search engine, Ullman’s responses

were evasive: “May I know whom you represent and why you are interested

in these issues? Who are your ‘sources’?” He also denied that Brin

played a significant role in developing the ‘query flocks’ system,

although it is clear from Brin’s papers that he did draw on that work in

co-developing the PageRank system with Page.

When

I asked Ullman whether he was denying the US intelligence community’s

role in supporting Brin during the development of Google, he said: “I am

not going to dignify this nonsense with a denial. If you won’t explain

what your theory is, and what point you are trying to make, I am not

going to help you in the slightest.”

The MDDS abstract

published online at the University of Texas confirms that the rationale

for the CIA-NSA project was to “provide seed money to develop data

management technologies which are of high-risk and high-pay-off,”

including techniques for “querying, browsing, and filtering; transaction

processing; accesses methods and indexing; metadata management and data

modelling; and integrating heterogeneous databases; as well as

developing appropriate architectures.” The ultimate vision of the

program was to “provide for the seamless access and fusion of massive

amounts of data, information and knowledge in a heterogeneous, real-time

environment” for use by the Pentagon, intelligence community and

potentially across government.

These

revelations corroborate the claims of Robert Steele, former senior CIA

officer and a founding civilian deputy director of the Marine Corps

Intelligence Activity, whom I interviewed for The Guardian last year on open source intelligence. Citing sources at the CIA, Steele had said

in 2006 that Steinheiser, an old colleague of his, was the CIA’s main

liaison at Google and had arranged early funding for the pioneering IT

firm. At the time, Wired founder John Batelle managed to get this official denial from a Google spokesperson in response to Steele’s assertions:

“The statements related to Google are completely untrue.”

This time round, despite multiple requests and conversations, a Google spokesperson declined to comment.

UPDATE:

As of 5.41PM GMT, Google’s director of corporate communication got in

touch and asked me to include the following statement:

“Sergey Brin was not part of the Query Flocks Program at Stanford, nor were any of his projects funded by US Intelligence bodies.”

This is what I wrote back:

My response to that statement would be as follows: Brin himself in his own paper acknowledges funding from the Community Management Staff of the Massive Digital Data Systems (MDDS) initiative, which was supplied through the NSF. The MDDS was an intelligence community program set up by the CIA and NSA. I also have it on record, as noted in the piece, from Prof. Thuraisingham of University of Texas that she managed the MDDS program on behalf of the US intelligence community, and that her and the CIA’s Rick Steinheiser met Brin every three months or so for two years to be briefed on his progress developing Google and PageRank. Whether Brin worked on query flocks or not is neither here nor there.

In that context, you might want to consider the following questions:

1) Does Google deny that Brin’s work was part-funded by the MDDS via an NSF grant?

2) Does Google deny that Brin reported regularly to Thuraisingham and Steinheiser from around 1996 to 1998 until September that year when he presented the Google search engine to them?

Total Information Awareness

A call for papers for the MDDS was sent out via email list

on November 3rd 1993 from senior US intelligence official David

Charvonia, director of the research and development coordination office

of the intelligence community’s CMS. The reaction from Tatu Ylonen

(celebrated inventor of the widely used secure shell [SSH] data

protection protocol) to his colleagues on the email list is telling:

“Crypto relevance? Makes you think whether you should protect your

data.” The email also confirms that defense contractor and Highlands

Forum partner, SAIC, was managing the MDDS submission process, with abstracts to be sent to Jackie Booth of the CIA’s Office of Research and Development via a SAIC email address.

By

1997, Thuraisingham reveals, shortly before Google became incorporated

and while she was still overseeing the development of its search engine

software at Stanford, her thoughts turned to the national security

applications of the MDDS program. In the acknowledgements to her book, Web Data Mining and Applications in Business Intelligence and Counter-Terrorism (2003),

Thuraisingham writes that she and “Dr. Rick Steinheiser of the CIA,

began discussions with Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on

applying data-mining for counter-terrorism,” an idea that resulted

directly from the MDDS program which partly funded Google. “These

discussions eventually developed into the current EELD (Evidence

Extraction and Link Detection) program at DARPA.”

So

the very same senior CIA official and CIA-NSA contractor involved in

providing the seed-funding for Google were simultaneously contemplating

the role of data-mining for counter-terrorism purposes, and were

developing ideas for tools actually advanced by DARPA.

Today, as illustrated by her recent oped in the New York Times,

Thuraisingham remains a staunch advocate of data-mining for

counter-terrorism purposes, but also insists that these methods must be

developed by government in cooperation with civil liberties lawyers and

privacy advocates to ensure that robust procedures are in place to

prevent potential abuse. She points out, damningly, that with the

quantity of information being collected, there is a high risk of false

positives.

In 1993, when the

MDDS program was launched and managed by MITRE Corp. on behalf of the

US intelligence community, University of Virginia computer scientist Dr.

Anita K. Jones — a MITRE trustee — landed the job of DARPA director and

head of research and engineering across the Pentagon. She had been on

the board of MITRE since 1988. From 1987 to 1993, Jones

simultaneously served on SAIC’s board of directors. As the new head of

DARPA from 1993 to 1997, she also co-chaired the Pentagon’s Highlands

Forum during the period of Google’s pre-launch development at Stanford

under the MDSS.

Thus, when

Thuraisingham and Steinheiser were talking to DARPA about the

counter-terrorism applications of MDDS research, Jones was DARPA

director and Highlands Forum co-chair. That year, Jones left DARPA to

return to her post at the University of Virgina. The following year, she

joined the board of the National Science Foundation, which of course

had also just funded Brin and Page, and also returned to the board of

SAIC. When she left DoD, Senator Chuck Robb paid Jones the following tribute :

“She brought the technology and operational military communities

together to design detailed plans to sustain US dominance on the

battlefield into the next century.”

On the board

of the National Science Foundation from 1992 to 1998 (including a stint

as chairman from 1996) was Richard N. Zare. This was the period in

which the NSF sponsored Sergey Brin and Larry Page in association with

DARPA. In June 1994, Prof. Zare, a chemist at Stanford, participated

with Prof. Jeffrey Ullman (who supervised Sergey Brin’s research), on a panel

sponsored by Stanford and the National Research Council discussing the

need for scientists to show how their work “ties to national needs.” The

panel brought together scientists and policymakers, including

“Washington insiders.”

DARPA’s

EELD program, inspired by the work of Thuraisingham and Steinheiser

under Jones’ watch, was rapidly adapted and integrated with a suite of

tools to conduct comprehensive surveillance under the Bush

administration.

According to DARPA official Ted Senator,

who led the EELD program for the agency’s short-lived Information

Awareness Office, EELD was among a range of “promising techniques” being

prepared for integration “into the prototype TIA system.” TIA stood for

Total Information Awareness, and was the main global electronic eavesdropping and data-mining program

deployed by the Bush administration after 9/11. TIA had been set up by

Iran-Contra conspirator Admiral John Poindexter, who was appointed in

2002 by Bush to lead DARPA’s new Information Awareness Office.

The

Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) was another contractor among 26

companies (also including SAIC) that received million dollar contracts

from DARPA

(the specific quantities remained classified) under Poindexter, to push

forward the TIA surveillance program in 2002 onwards. The research

included “behaviour-based profiling,” “automated detection,

identification and tracking” of terrorist activity, among other

data-analyzing projects. At this time, PARC’s director and chief

scientist was John Seely Brown. Both Brown and Poindexter were Pentagon

Highlands Forum participants — Brown on a regular basis until recently.

TIA

was purportedly shut down in 2003 due to public opposition after the

program was exposed in the media, but the following year Poindexter

participated in a Pentagon Highlands Group session in Singapore,

alongside defense and security officials from around the world.

Meanwhile, Ted Senator continued to manage the EELD program among other

data-mining and analysis projects at DARPA until 2006, when he left to

become a vice president at SAIC. He is now a SAIC/Leidos technical

fellow.

Google, DARPA and the money trail

Long

before the appearance of Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Stanford

University’s computer science department had a close working

relationship with US military intelligence. A letter

dated November 5th 1984 from the office of renowned artificial

intelligence (AI) expert, Prof Edward Feigenbaum, addressed to Rick

Steinheiser, gives the latter directions to Stanford’s Heuristic

Programming Project, addressing Steinheiser as a member of the “AI

Steering Committee.” A list

of attendees at a contractor conference around that time, sponsored by

the Pentagon’s Office of Naval Research (ONR), includes Steinheiser as a

delegate under the designation “OPNAV Op-115” — which refers to the

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations’ program on operational

readiness, which played a major role in advancing digital systems for

the military.

From the 1970s, Prof. Feigenbaum and his colleagues had been running Stanford’s Heuristic Programming Project under contract with DARPA, continuing through to the 1990s. Feigenbaum alone had received around over $7 million in this period for his work from DARPA, along with other funding from the NSF, NASA, and ONR.

Brin’s

supervisor at Stanford, Prof. Jeffrey Ullman, was in 1996 part of a

joint funding project of DARPA’s Intelligent Integration of Information program. That year, Ullman co-chaired DARPA-sponsored meetings on data exchange between multiple systems.

In

September 1998, the same month that Sergey Brin briefed US intelligence

representatives Steinheiser and Thuraisingham, tech entrepreneurs

Andreas Bechtolsheim and David Cheriton invested $100,000 each in

Google. Both investors were connected to DARPA.

As a Stanford PhD student in electrical engineering in the 1980s, Bechtolsheim’s pioneering SUN workstation project had been funded

by DARPA and the Stanford computer science department — this research

was the foundation of Bechtolsheim’s establishment of Sun Microsystems,

which he co-founded with William Joy.

As

for Bechtolsheim’s co-investor in Google, David Cheriton, the latter is

a long-time Stanford computer science professor who has an even more

entrenched relationship with DARPA. His bio

at the University of Alberta, which in November 2014 awarded him an

honorary science doctorate, says that Cheriton’s “research has received

the support of the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

for over 20 years.”

In the

meantime, Bechtolsheim left Sun Microsystems in 1995, co-founding

Granite Systems with his fellow Google investor Cheriton as a partner.

They sold Granite to Cisco Systems in 1996, retaining significant

ownership of Granite, and becoming senior Cisco executives.

An

email obtained from the Enron Corpus (a database of 600,000 emails

acquired by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and later released

to the public) from Richard O’Neill, inviting Enron executives to

participate in the Highlands Forum, shows that Cisco and Granite

executives are intimately connected to the Pentagon. The email reveals

that in May 2000, Bechtolsheim’s partner and Sun Microsystems

co-founder, William Joy — who was then chief scientist and corporate

executive officer there — had attended the Forum to discuss

nanotechnology and molecular computing.

In

1999, Joy had also co-chaired the President’s Information Technology

Advisory Committee, overseeing a report acknowledging that DARPA had:

“… revised its priorities in the 90’s so that all information technology funding was judged in terms of its benefit to the warfighter.”

Throughout

the 1990s, then, DARPA’s funding to Stanford, including Google, was

explicitly about developing technologies that could augment the

Pentagon’s military intelligence operations in war theatres.

The

Joy report recommended more federal government funding from the

Pentagon, NASA, and other agencies to the IT sector. Greg Papadopoulos,

another of Bechtolsheim’s colleagues as then Sun Microsystems chief

technology officer, also attended a Pentagon Highlands’ Forum meeting in

September 2000.

In

November, the Pentagon Highlands Forum hosted Sue Bostrom, who was vice

president for the internet at Cisco, sitting on the company’s board

alongside Google co-investors Bechtolsheim and Cheriton. The Forum also

hosted Lawrence Zuriff, then a managing partner of Granite, which

Bechtolsheim and Cheriton had sold to Cisco. Zuriff had previously been

an SAIC contractor from 1993 to 1994, working with the Pentagon on

national security issues, specifically for Marshall’s Office of Net

Assessment. In 1994, both the SAIC and the ONA were, of course, involved

in co-establishing the Pentagon Highlands Forum. Among Zuriff’s output

during his SAIC tenure was a paper titled ‘Understanding Information War’, delivered at a SAIC-sponsored US Army Roundtable on the Revolution in Military Affairs.

After

Google’s incorporation, the company received $25 million in equity

funding in 1999 led by Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins Caufield

& Byers. According to Homeland Security Today,

“A number of Sequoia-bankrolled start-ups have contracted with the

Department of Defense, especially after 9/11 when Sequoia’s Mark Kvamme

met with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to discuss the application of

emerging technologies to warfighting and intelligence collection.”

Similarly, Kleiner Perkins had developed “a close relationship” with

In-Q-Tel, the CIA venture capitalist firm that funds start-ups “to

advance ‘priority’ technologies of value” to the intelligence community.

John

Doerr, who led the Kleiner Perkins investment in Google obtaining a

board position, was a major early investor in Becholshtein’s Sun

Microsystems at its launch. He and his wife Anne are the main funders

behind Rice University’s Center for Engineering Leadership (RCEL), which

in 2009 received

$16 million from DARPA for its platform-aware-compilation-environment

(PACE) ubiquitous computing R&D program. Doerr also has a close

relationship with the Obama administration, which he advised shortly

after it took power to ramp up Pentagon funding to the tech industry. In 2013, at the Fortune Brainstorm TECH conference,

Doerr applauded “how the DoD’s DARPA funded GPS, CAD, most of the major

computer science departments, and of course, the Internet.”

From

inception, in other words, Google was incubated, nurtured and financed

by interests that were directly affiliated or closely aligned with the

US military intelligence community: many of whom were embedded in the

Pentagon Highlands Forum.

Google captures the Pentagon

In 2003, Google began customizing its search engine under special contract

with the CIA for its Intelink Management Office, “overseeing

top-secret, secret and sensitive but unclassified intranets for CIA and

other IC agencies,” according to Homeland Security Today. That

year, CIA funding was also being “quietly” funneled through the

National Science Foundation to projects that might help create “new

capabilities to combat terrorism through advanced technology.”

The following year, Google bought the firm Keyhole,

which had originally been funded by In-Q-Tel. Using Keyhole, Google

began developing the advanced satellite mapping software behind Google

Earth. Former DARPA director and Highlands Forum co-chair Anita Jones

had been on the board of In-Q-Tel at this time, and remains so today.

Then

in November 2005, In-Q-Tel issued notices to sell $2.2 million of

Google stocks. Google’s relationship with US intelligence was further

brought to light when an IT contractor

told a closed Washington DC conference of intelligence professionals on

a not-for-attribution basis that at least one US intelligence agency

was working to “leverage Google’s [user] data monitoring” capability as

part of an effort to acquire data of “national security intelligence

interest.”

A photo

on Flickr dated March 2007 reveals that Google research director and AI

expert Peter Norvig attended a Pentagon Highlands Forum meeting that

year in Carmel, California. Norvig’s intimate connection to the Forum as

of that year is also corroborated by his role in guest editing the 2007 Forum reading list.

The

photo below shows Norvig in conversation with Lewis Shepherd, who at

that time was senior technology officer at the Defense Intelligence

Agency, responsible for

investigating, approving, and architecting “all new hardware/software

systems and acquisitions for the Global Defense Intelligence IT

Enterprise,” including “big data technologies.” Shepherd now works at

Microsoft. Norvig was a computer research scientist at Stanford

University in 1991 before joining Bechtolsheim’s Sun Microsystems as

senior scientist until 1994, and going on to head up NASA’s computer

science division.

Norvig shows up on O’Neill’s Google Plus profile

as one of his close connections. Scoping the rest of O’Neill’s Google

Plus connections illustrates that he is directly connected not just to a

wide range of Google executives, but also to some of the biggest names

in the US tech community.

Those

connections include Michele Weslander Quaid, an ex-CIA contractor and

former senior Pentagon intelligence official who is now Google’s chief

technology officer where she is developing programs

to “best fit government agencies’ needs”; Elizabeth Churchill, Google

director of user experience; James Kuffner, a humanoid robotics expert

who now heads up Google’s robotics division and who introduced the term

‘cloud robotics’; Mark Drapeau, director of innovation engagement for

Microsoft’s public sector business; Lili Cheng, general manager of

Microsoft’s Future Social Experiences (FUSE) Labs; Jon Udell, Microsoft

‘evangelist’; Cory Ondrejka, vice president of engineering at Facebook;

to name just a few.

In 2010, Google signed a multi-billion dollar no-bid contract

with the NSA’s sister agency, the National Geospatial-Intelligence

Agency (NGA). The contract was to use Google Earth for visualization

services for the NGA. Google had developed the software behind Google

Earth by purchasing Keyhole from the CIA venture firm In-Q-Tel.

Then

a year after, in 2011, another of O’Neill’s Google Plus connections,

Michele Quaid — who had served in executive positions at the NGA,

National Reconnaissance Office and the Office of the Director of

National Intelligence — left her government role to become Google

‘innovation evangelist’ and the point-person for seeking government

contracts. Quaid’s last role before her move to Google was as a senior

representative of the Director of National Intelligence to the

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Task Force, and a senior

advisor to the undersecretary of defense for intelligence’s director of

Joint and Coalition Warfighter Support (J&CWS). Both roles involved

information operations at their core. Before her Google move, in other

words, Quaid worked closely with the Office of the Undersecretary of

Defense for Intelligence, to which the Pentagon’s Highlands Forum is

subordinate. Quaid has herself attended the Forum, though precisely when

and how often I could not confirm.

In March 2012, then DARPA director Regina Dugan

— who in that capacity was also co-chair of the Pentagon Highlands

Forum — followed her colleague Quaid into Google to lead the company’s

new Advanced Technology and Projects Group. During her Pentagon tenure,

Dugan led on strategic cyber security and social media, among other

initiatives. She was responsible for focusing “an increasing portion” of

DARPA’s work “on the investigation of offensive capabilities to address

military-specific needs,” securing $500 million of government funding

for DARPA cyber research from 2012 to 2017.

By November 2014, Google’s chief AI and robotics expert James Kuffner was a delegate alongside O’Neill at the Highlands Island Forum 2014

in Singapore, to explore ‘Advancement in Robotics and Artificial

Intelligence: Implications for Society, Security and Conflict.’ The

event included 26 delegates

from Austria, Israel, Japan, Singapore, Sweden, Britain and the US,

from both industry and government. Kuffner’s association with the

Pentagon, however, began much earlier. In 1997, Kuffner was a researcher

during his Stanford PhD for a Pentagon-funded project on networked autonomous mobile robots, sponsored by DARPA and the US Navy.

Rumsfeld and persistent surveillance

In

sum, many of Google’s most senior executives are affiliated with the

Pentagon Highlands Forum, which throughout the period of Google’s growth

over the last decade, has surfaced repeatedly as a connecting and

convening force. The US intelligence community’s incubation of Google

from inception occurred through a combination of direct sponsorship and

informal networks of financial influence, themselves closely aligned

with Pentagon interests.

The

Highlands Forum itself has used the informal relationship building of

such private networks to bring together defense and industry sectors,

enabling the fusion of corporate and military interests in expanding the

covert surveillance apparatus in the name of national security. The

power wielded by the shadow network represented in the Forum can,

however, be gauged most clearly from its impact during the Bush

administration, when it played a direct role in literally writing the

strategies and doctrines behind US efforts to achieve ‘information

superiority.’

In December 2001, O’Neill confirmed

that strategic discussions at the Highlands Forum were feeding directly

into Andrew Marshall’s DoD-wide strategic review ordered by President

Bush and Donald Rumsfeld to upgrade the military, including the

Quadrennial Defense Review — and that some of the earliest Forum

meetings “resulted in the writing of a group of DoD policies,

strategies, and doctrine for the services on information warfare.” That

process of “writing” the Pentagon’s information warfare policies “was

done in conjunction with people who understood the environment

differently — not only US citizens, but also foreign citizens, and

people who were developing corporate IT.”

The

Pentagon’s post-9/11 information warfare doctrines were, then, written

not just by national security officials from the US and abroad: but also

by powerful corporate entities in the defense and technology sectors.

In April that year, Gen. James McCarthy had completed his defense transformation review

ordered by Rumsfeld. His report repeatedly highlighted mass

surveillance as integral to DoD transformation. As for Marshall, his

follow-up report for Rumsfeld was going to develop a blueprint determining the Pentagon’s future in the ‘information age.’

O’Neill also affirmed that to develop information warfare doctrine, the Forum had held extensive discussions

on electronic surveillance and “what constitutes an act of war in an

information environment.” Papers feeding into US defense policy written

through the late 1990s by RAND consultants John Arquilla and David

Rondfeldt, both longstanding Highlands Forum members, were produced “as a

result of those meetings,” exploring policy dilemmas on how far to take

the goal of ‘Information Superiority.’ “One of the things that was

shocking to the American public was that we weren’t pilfering

Milosevic’s accounts electronically when we in fact could,” commented

O’Neill.

Although the

R&D process around the Pentagon transformation strategy remains

classified, a hint at the DoD discussions going on in this period can be

gleaned from a 2005 US Army School of Advanced Military Studies

research monograph in the DoD journal, Military Review, authored by an active Army intelligence officer.

“The

idea of Persistent Surveillance as a transformational capability has

circulated within the national Intelligence Community (IC) and the

Department of Defense (DoD) for at least three years,” the paper said,

referencing the Rumsfeld-commissioned transformation study.

The

Army paper went on to review a range of high-level official military

documents, including one from the Office of the Chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, showing that “Persistent Surveillance” was a

fundamental theme of the information-centric vision for defense policy

across the Pentagon.

We now know that just two months before O’Neill’s address at Harvard in 2001, under the TIA program, President Bush had secretly authorized

the NSA’s domestic surveillance of Americans without court-approved

warrants, in what appears to have been an illegal modification of the

ThinThread data-mining project — as later exposed by NSA whistleblowers William Binney and Thomas Drake.

The surveillance-startup nexus

From

here on, Highlands Forum partner SAIC played a key role in the NSA roll

out from inception. Shortly after 9/11, Brian Sharkey, chief technology

officer of SAIC’s ELS3 Sector (focusing on IT systems for emergency

responders), teamed up with John Poindexter to propose the TIA

surveillance program. SAIC’s Sharkey had previously been deputy director of the Information Systems Office at DARPA through the 1990s.

Meanwhile, around the same time, SAIC vice president for corporate development, Samuel Visner,

became head of the NSA’s signals-intelligence programs. SAIC was then

among a consortium receiving a $280 million contract to develop one of

the NSA’s secret eavesdropping systems. By 2003, Visner returned to SAIC

to become director of strategic planning and business development of

the firm’s intelligence group.

That year, the NSA consolidated its TIA

programme of warrantless electronic surveillance, to keep “track of

individuals” and understand “how they fit into models” through risk

profiles of American citizens and foreigners. TIA was doing this by

integrating databases on finance, travel, medical, educational and other

records into a “virtual, centralized grand database.”

This was also the year that the Bush administration drew up its notorious Information Operations Roadmap.

Describing the internet as a “vulnerable weapons system,” Rumsfeld’s IO

roadmap had advocated that Pentagon strategy “should be based on the

premise that the Department [of Defense] will ‘fight the net’ as it

would an enemy weapons system.” The US should seek “maximum control” of

the “full spectrum of globally emerging communications systems, sensors,

and weapons systems,” advocated the document.

The

following year, John Poindexter, who had proposed and run the TIA

surveillance program via his post at DARPA, was in Singapore

participating in the Highlands 2004 Island Forum.

Other delegates included then Highlands Forum co-chair and Pentagon CIO

Linton Wells; president of notorious Pentagon information warfare

contractor, John Rendon; Karl Lowe, director of the Joint Forces Command

(JFCOM) Joint Advanced Warfighting Division; Air Vice Marshall Stephen

Dalton, capability manager for information superiority at the UK

Ministry of Defense; Lt. Gen. Johan Kihl, Swedish army Supreme Commander

HQ’s chief of staff; among others.

As of 2006, SAIC had been awarded a multi-million dollar NSA contract to develop a big data-mining project called ExecuteLocus,

despite the colossal $1 billion failure of its preceding contract,

known as ‘Trailblazer.’ Core components of TIA were being “quietly

continued” under “new code names,” according to Foreign Policy’s Shane Harris,

but had been concealed “behind the veil of the classified intelligence

budget.” The new surveillance program had by then been fully

transitioned from DARPA’s jurisdiction to the NSA.

This

was also the year of yet another Singapore Island Forum led by Richard

O’Neill on behalf of the Pentagon, which included senior defense and

industry officials from the US, UK, Australia, France, India and Israel.

Participants also included senior technologists from Microsoft, IBM, as

well as Gilman Louie, partner at technology investment firm Alsop Louie Partners.

Gilman

Louie is a former CEO of In-Q-Tel — the CIA firm investing especially

in start-ups developing data mining technology. In-Q-Tel was founded in

1999 by the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, under which the

Office of Research and Development (ORD) — which was part of the

Google-funding MDSS program — had operated. The idea was to essentially

replace the functions once performed by the ORD, by mobilizing the

private sector to develop information technology solutions for the

entire intelligence community.

Louie

had led In-Q-Tel from 1999 until January 2006 — including when Google

bought Keyhole, the In-Q-Tel-funded satellite mapping software. Among

his colleagues on In-Q-Tel’s board in this period were former DARPA

director and Highlands Forum co-chair Anita Jones (who is still there),

as well as founding board member William Perry:

the man who had appointed O’Neill to set-up the Highlands Forum in the

first place. Joining Perry as a founding In-Q-Tel board member was John

Seely Brown, then chief scientist at Xerox Corp and director of its Palo

Alto Research Center (PARC) from 1990 to 2002, who is also a long-time

senior Highlands Forum member since inception.

In

addition to the CIA, In-Q-Tel has also been backed by the FBI, NGA, and

Defense Intelligence Agency, among other agencies. More than 60 percent

of In-Q-Tel’s investments under Louie’s watch were “in companies that

specialize in automatically collecting, sifting through and

understanding oceans of information,” according to Medill School of

Journalism’s News21,

which also noted that Louie himself had acknowledged it was not clear

“whether privacy and civil liberties will be protected” by government’s

use of these technologies “for national security.”

The transcript

of Richard O’Neill’s late 2001 seminar at Harvard shows that the

Pentagon Highlands Forum had first engaged Gilman Louie long before the

Island Forum, in fact, shortly after 9/11 to explore “what’s going on

with In-Q-Tel.” That Forum session focused on how to “take advantage of

the speed of the commercial market that wasn’t present inside the

science and technology community of Washington” and to understand “the

implications for the DoD in terms of the strategic review, the QDR, Hill

action, and the stakeholders.” Participants of the meeting included

“senior military people,” combatant commanders, “several of the senior

flag officers,” some “defense industry people” and various US

representatives including Republican Congressman William Mac Thornberry

and Democrat Senator Joseph Lieberman.

Both

Thornberry and Lieberman are staunch supporters of NSA surveillance,

and have consistently acted to rally support for pro-war,

pro-surveillance legislation. O’Neill’s comments indicate that the

Forum’s role is not just to enable corporate contractors to write

Pentagon policy, but to rally political support for government policies

adopted through the Forum’s informal brand of shadow networking.

Repeatedly,

O’Neill told his Harvard audience that his job as Forum president was

to scope case studies from real companies across the private sector,

like eBay and Human Genome Sciences, to figure out the basis of US

‘Information Superiority’ — “how to dominate” the information

market — and leverage this for “what the president and the secretary of

defense wanted to do with regard to transformation of the DoD and the

strategic review.”

By 2007, a

year after the Island Forum meeting that included Gilman Louie,

Facebook received its second round of $12.7 million worth of funding

from Accel Partners. Accel was headed up by James Breyer, former chair

of the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) where Louie also served on the board while still CEO of In-Q-Tel. Both Louie and Breyer had previously served together on the board of BBN Technologies — which had recruited ex-DARPA chief and In-Q-Tel trustee Anita Jones.

Facebook’s

2008 round of funding was led by Greylock Venture Capital, which

invested $27.5 million. The firm’s senior partners include Howard Cox,

another former NVCA chair who also sits on the board

of In-Q-Tel. Apart from Breyer and Zuckerberg, Facebook’s only other

board member is Peter Thiel, co-founder of defense contractor Palantir

which provides all sorts of data-mining and visualization technologies

to US government, military and intelligence agencies, including the NSA and FBI, and which itself was nurtured to financial viability by Highlands Forum members.

Palantir co-founders Thiel and Alex Karp met with John Poindexter in 2004, according to Wired,

the same year Poindexter had attended the Highlands Island Forum in

Singapore. They met at the home of Richard Perle, another Andrew

Marshall acolyte. Poindexter helped Palantir open doors, and to assemble

“a legion of advocates from the most influential strata of government.”

Thiel had also met with Gilman Louie of In-Q-Tel, securing the backing

of the CIA in this early phase.

And

so we come full circle. Data-mining programs like ExecuteLocus and

projects linked to it, which were developed throughout this period,

apparently laid the groundwork for the new NSA programmes eventually

disclosed by Edward Snowden. By 2008, as Facebook received its next

funding round from Greylock Venture Capital, documents and whistleblower

testimony confirmed that the NSA was effectively resurrecting the TIA project with a focus on Internet data-mining via comprehensive monitoring of e-mail, text messages, and Web browsing.

We also now know thanks to Snowden that the NSA’s XKeyscore

‘Digital Network Intelligence’ exploitation system was designed to

allow analysts to search not just Internet databases like emails, online

chats and browsing history, but also telephone services, mobile phone

audio, financial transactions and global air transport

communications — essentially the entire global telecommunications grid.

Highlands Forum partner SAIC played a key role, among other contractors,

in producing and administering the NSA’s XKeyscore, and was recently implicated in NSA hacking of the privacy network Tor.

The

Pentagon Highlands Forum was therefore intimately involved in all this

as a convening network—but also quite directly. Confirming his pivotal

role in the expansion of the US-led global surveillance apparatus, then

Forum co-chair, Pentagon CIO Linton Wells, told FedTech magazine

in 2009 that he had overseen the NSA’s roll out of “an impressive

long-term architecture last summer that will provide increasingly

sophisticated security until 2015 or so.”

The Goldman Sachs connection

When

I asked Wells about the Forum’s role in influencing US mass

surveillance, he responded only to say he would prefer not to comment

and that he no longer leads the group.

As

Wells is no longer in government, this is to be expected — but he is

still connected to Highlands. As of September 2014, after delivering his

influential white paper on Pentagon transformation, he joined the

Monterey Institute for International Studies (MIIS) Cyber Security

Initiative (CySec) as a distinguished senior fellow.

Sadly,

this was not a form of trying to keep busy in retirement. Wells’ move

underscored that the Pentagon’s conception of information warfare is not

just about surveillance, but about the exploitation of surveillance to

influence both government and public opinion.

The MIIS CySec initiative is now formally partnered with the Pentagon Highlands Forum through a Memorandum of Understanding signed with MIIS provost Dr Amy Sands,

who sits on the Secretary of State’s International Security Advisory

Board. The MIIS CySec website states that the MoU signed with Richard

O’Neill:

“… paves the way for future joint MIIS CySec-Highlands Group sessions that will explore the impact of technology on security, peace and information engagement. For nearly 20 years the Highlands Group has engaged private sector and government leaders, including the Director of National Intelligence, DARPA, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Homeland Security and the Singaporean Minister of Defence, in creative conversations to frame policy and technology research areas.”

Who is the financial benefactor of the new Pentagon Highlands-partnered MIIS CySec initiative? According to the MIIS CySec site,

the initiative was launched “through a generous donation of seed

funding from George Lee.” George C. Lee is a senior partner at Goldman

Sachs, where he is chief information officer of the investment banking

division, and chairman of the Global Technology, Media and Telecom (TMT)

Group.

But here’s the kicker. In 2011, it was Lee who engineered Facebook’s $50 billion valuation,

and previously handled deals for other Highlands-connected tech giants

like Google, Microsoft and eBay. Lee’s then boss, Stephen Friedman, a

former CEO and chairman of Goldman Sachs, and later senior partner on

the firm’s executive board, was a also founding board member of In-Q-Tel alongside Highlands Forum overlord William Perry and Forum member John Seely Brown.

In

2001, Bush appointed Stephen Friedman to the President’s Intelligence

Advisory Board, and then to chair that board from 2005 to 2009. Friedman

previously served alongside Paul Wolfowitz and others on the 1995–6

presidential commission of inquiry into US intelligence capabilities,

and in 1996 on the Jeremiah Panel

that produced a report to the Director of the National Reconnaisance

Office (NRO) — one of the surveillance agencies plugged into the

Highlands Forum. Friedman was on the Jeremiah Panel with Martin Faga,

then senior vice president and general manager of MITRE Corp’s Center

for Integrated Intelligence Systems — where Thuraisingham, who managed

the CIA-NSA-MDDS program that inspired DARPA counter-terrorist

data-mining, was also a lead engineer.

In the footnotes to a chapter for the book, Cyberspace and National Security (Georgetown

University Press), SAIC/Leidos executive Jeff Cooper reveals that

another Goldman Sachs senior partner Philip J. Venables — who as chief

information risk officer leads the firm’s programs on information

security — delivered a Highlands Forum presentation in 2008 at what was

called an ‘Enrichment Session on Deterrence.’ Cooper’s chapter draws on

Venables’ presentation at Highlands “with permission.” In 2010, Venables

participated with his then boss Friedman at an Aspen Institute meeting on the world economy. For the last few years, Venables has also sat on various NSA cybersecurity award review boards.

In

sum, the investment firm responsible for creating the billion dollar

fortunes of the tech sensations of the 21st century, from Google to

Facebook, is intimately linked to the US military intelligence

community; with Venables, Lee and Friedman either directly connected to

the Pentagon Highlands Forum, or to senior members of the Forum.

Fighting terror with terror

The

convergence of these powerful financial and military interests around

the Highlands Forum, through George Lee’s sponsorship of the Forum’s new

partner, the MIIS Cysec initiative, is revealing in itself.

MIIS

Cysec’s director, Dr, Itamara Lochard, has long been embedded in

Highlands. She regularly “presents current research on non-state groups,

governance, technology and conflict to the US Office of the Secretary

of Defense Highlands Forum,” according to her Tufts University bio. She also,

“regularly advises US combatant commanders” and specializes in studying