When spammers go to war: Behind the Spamhaus DDoS

The story behind the 300Gb/s attack on an anti-spam organization.

Sven Olaf Kamphuis waving the Pirate Party flag in front of CyberBunker's nuclear bunker.

The New York Times reported recently that the attacks came from a Dutch hosting company called CyberBunker (also known as cb3rob), which owns and operates a real military bunker and which has been targeted in the past by Spamhaus. The spokesman who the NYT interviewed, Sven Olaf Kamphuis, has since posted on his Facebook page that CyberBunker is not orchestrating the attacks. Kamphuis also claimed that NYT was plumping for sensationalism over accuracy.

Sven Olaf Kamphuis is, however, affiliated with the newly organized group "STOPhaus." STOPhaus claims that Spamhaus is "an offshore criminal network of tax circumventing self declared internet terrorists pretending to be 'spam' fighters" that is "attempt[ing] to control the internet through underhanded extortion tactics."

STOPhaus claims to have the support of "half the Russian and Chinese Internet industry." It wants nothing less than to put Spamhaus out of action, and it looks like it's not too picky about how that might be accomplished. And if Spamhaus won’t back down, Kamphuis has made clear that even more data can be thrown at the anti-spammers.

Escalation

Hating Spamhaus has a long history.Spamhaus is a nonprofit organization based in London and Geneva that was started in 1998 as a way of combating the escalating spam problem. The group doesn't block any data itself, but it does operate a number of blacklist services used by others to block data.

The first of these was the Spamhaus Block List (SBL), a database of IP addresses known to be spam originators. E-mail servers can query the SBL for each incoming e-mail to see if the connection is being made from an IP address in the database. If it is, they can reject the connection as being a probable cause of spam.

SBL tended to be filled with machines that were, for one reason or another, operating as open relays. The protocol used for sending e-mail, SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) has a feature that nowadays might be considered rather undesirable: in principle, any SMTP server can be used to send e-mail from any sender to any recipient. If the SMTP server isn't responsible for the message box that a mail is being sent to, it should look up the server that is responsible for the message box and forward the message on to that server, a process called "relaying," and servers that operate in this way are “open” relays.

This is great for spammers. They can use a bogus address for the sender and the victim's address for the recipient, then use any open relay to actually send that message. The open relay will then find the real recipient server and forward the message.

This is obviously undesirable, so most SMTP servers these days apply additional rules. For example, ISP-operated mail servers will often operate as relays, but with some restrictions: they'll only allow relaying if the connection is being made from an IP address that belongs to the ISP. Or they will require a username and password to access.

As awareness of the problem of open relays has grown and the number of useful open relays has dropped, spammers have moved to other approaches. Instead of sending mail through a relay, they more commonly send it from machines they control directly to the recipient's mail server.

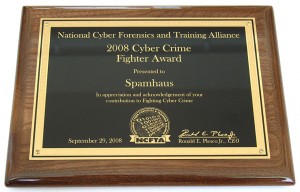

Enlarge / Spammers may hate them, but some people quite approve of the work Spamhaus does.

To counter this kind of thing, some blacklist operators operate blacklists of "client" IP addresses, addresses used by consumer-focused ISPs that, for the most part, shouldn't be directly sending mail at all (instead, they should be routing mail through their ISPs' respective mail relays). Spamhaus operates such a list, separate from the SBL, calling it the Policy Block List. Spamhaus also has a database of compromised machines, the Exploits Block List, that lists hijacked machines running spam-related malware.

Spamhaus has a number of criteria that can result in an IP address being listed in its database. The organization has a number of Spamtrap e-mail addresses; addresses which won't ever receive legitimate mail (because nobody actually uses them). This is the most obvious source of IP addresses, and probably the least controversial—if an IP address sends spam to an inbox, it's fair game to regard that IP address as a spam source.

Spamhaus also blocks "spam operations," which is to say companies it believes make a business of sending spam. It lists these in its Register of Known Spam Operations (ROKSO), and it will pre-emptively blacklist IP addresses used by these groups. (Spamhaus will blacklist "spam support services"—ISPs and other service operators known to be spam friendly, for example by offering Web hosting to spammers, hosting spam servers, or selling spam software.)

The organization's most severe measure is its DROP ("don't route or peer") list. The DROP list is a list of IP address blocks that are controlled by criminals and spammers. Routers can use these to block all traffic from these IP ranges. Rather than using DNS, this list is distributed as a text file, for manual configuration, and using the BGP protocol, for routers to use directly.

In addition to the lists it maintains and the different inclusion criteria, Spamhaus has one particularly important policy: escalation. Repeated infringement—such as an ISP that refuses to terminate the service of spammers on its network—will see Spamhaus move beyond blacklisting individual IP addresses and start blacklisting ranges. If behavior still isn't improved, Spamhaus will block ever-larger ranges.

All of these policies, predictably, have caused conflict.

Going to war

Though Spamhaus does no blocking itself, groups that depend on spam tend to blame the company for their losses. This has resulted in court proceedings against the organization. In the US, now-defunct online marketing site e360insight sued Spamhaus after it was included on the ROKSO list, claiming that it had lost millions of dollars as a result of Spamhaus's decision.Being a UK-based company, Spamhaus initially ignored the lawsuit in the US, resulting in a default judgment against it, in which e360 was awarded almost $12 million in 2007. After US courts threatened to have Spamhaus's domain name suspended, the group decided at this point to get involved in the court case. Though the default judgment stood—if you don't show up at a civil case that's the risk you run—the $12 million judgment was overturned by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The case was bounced back to a lower court to decide on a new damages award.

The second time around, the court decided on damages of $27,002. Both sides appealed again. In 2011 the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals issued its second judgment on the issue. e360 was awarded damages of $3 after the court decided that e360 had failed to demonstrate the material impact of Spamhaus's decision and had instead wasted time and called a witness that "painted a wildly unrealistic picture" of e360s's losses. To add insult to injury, the court ordered e360 to pay Spamhaus's costs.

In every practical sense, this was a victory for Spamhaus and a loss for e360, though it didn't much matter by this point; e360 went out of business in 2008 or 2009 after engaging in numerous lawsuits against Internet users who had called it a spammer, and against Comcast for blocking e360's spam. It lost all these cases.

Obviously, those who make money from spamming will have a grievance with Spamhaus. But they're not the only ones, thanks in no small part to Spamhaus' escalation policy. Network providers and domain registries also fall foul of its policies from time to time.

Enlarge / In Spamhaus's view, cb3rob is the worst spam ISP in the world.

Spamhaus responded by putting nic.at's mail server in its blacklist under the "spam support services" category, arguing that nic.at let spammers keep using their domains. Ultimately, the domains were removed and nic.at was delisted.

These kinds of conflicts eventually led to a fight between Spamhaus and CyberBunker. Spamhaus regards CyberBunker—which has a policy of hosting any kind of content so long as it is not "child porn and anything related to terrorism"—as a spam support service. Spamhaus says that CyberBunker was at one point hosting Chinese sites selling spamvertised knock-off watches. CyberBunker says that this has never been proven, and it dismissed the complaints as "childish claims."

Spamhaus went upstream. CyberBunker bought its bandwidth from a company called DataHouse, which in turn bought bandwidth from Dutch service provider A2B Internet. In June 2011, Spamhaus asked A2B to cut off CyberBunker's network. A2B didn't, so in October 2011, Spamhaus added a range of 2,048 A2B-owned addresses to its blacklist.

E-mail correspondence between Spamhaus and A2B, published by A2B, eventually acknowledged that CyberBunker/cb3rob was hosting a spamvertised site. Shortly after this acknowledgement was made, A2B ceased routing for CyberBunker; five hours later Spamhaus removed A2B from the blacklist.

A2B subsequently filed a police complaint against Spamhaus, claiming that the group was engaged in "extortion" and was conducting "denial of e-mail service" attacks.

Stopping Spamhaus?

The collective opposition to Spamhaus has now produced STOPhaus. This is not the first group organizing to stop Spamhaus, and it comes after previous efforts such as stopspamhaus.org. The group dismisses Spamhaus' claim to only operate lists and perform no blocking itself as false and misleading to the public, and it claims that Spamhaus "violates multiple terrorism laws."STOPhaus members consistently describe Spamhaus' activity as "blackmail" and further argue that the information listed in ROKSO is "slander" [sic] and in violation of the UK's Data Protection Act. They also says that if Spamhaus detects criminal activity, it has the "legal obligation" to report this to law enforcement rather than to list offending IP addresses and domains in its databases. Finally, they claim that the DROP list is a violation of the "UK Computer Sabotage Act" (though no such act exists in the UK).

The style of the STOPhaus announcement is more than a little familiar to anyone who has followed Anonymous' various Internet activities. It mirrors the verbiage and slogans that have been a common feature of past Anonymous announcements.

The Anonymous similarities don't stop there. The STOPhaus forum contains preliminary attempts to dox people associated with Spamhaus and with anti-spam activities in general. (This includes Usenet group news.admin.net-abuse.email, where spam has been discussed since 1995, and Rob Pike, creator of the Plan 9 operating system and Google's Go programming language.)

Kamphuis says that his group probably owns a third of the Internet, and as such they're "perfectly free" to break it if they want.Besides claiming that Spamhaus is broadly criminal, STOPhaus asserts that Spamhaus threatens “net neutrality”; Spamhaus has such power that it can functionally deny people access to the Internet simply by listing them in its database. Despite all this alleged blocking, STOPhaus says that Spamhaus doesn't do one key thing: block spam. Not a single piece of it, apparently, not even as an accidental repercussion of the escalation policy.

On March 19 of this year, STOPhaus supporters announced "Operation STOPhaus," demanding that Spamhaus cease listing any IP addresses other than those known to send spam to its own spamtraps, and that it compensate everyone whose non-spamming IP address was ever listed.

Unsurprisingly, Spamhaus did not bow to the STOPhaus demands but instead complained to STOPhaus.com's hosting company, saying that the site was operated by a known spammer.

Spamhaus was then attacked with a DDoS attack of apparently unprecedented scale. Kamphuis says that, although he is not personally conducting the attacks, the people who are could throw "quite a bit more" data at the anti-spam organization if needed. While this may disrupt the Internet for others, Kamphuis says that his group probably owns a third of the Internet, and as such they're "perfectly free" to break it if they want.

If what Kamphuis says is true, Spamhaus can only expect the DDoS attacks to grow larger.

No end in sight

Assuming that the attack really is being made to the large Russian and Chinese Internet companies that Kamphuis says are involved, there's no particular reason for it to end any time soon. In some ways similar to the open SMTP relays of the past, two pieces of poor configuration are facilitating the attacks. Unlike open SMTP relays, these poor configurations are unlikely to go away any time soon.The specific issues are ISPs that allow forged traffic to leave their networks—something which has little good justification to permit—and open DNS servers that can be used to generate large responses in response to forged IP traffic. Together, these allow attack systems that begin with a few gigabits of bandwidth to generate enormous floods of data through “amplification attacks” capable of knocking any conventionally hosted server off the 'Net. Even if a concerted effort were made to fix these systems, it would probably take months, if not years, to make a serious dent in the problem.

As long as Spamhaus, its DDoS protection provider CloudFlare, and their respective connectivity providers are willing to tolerate the situation, they too don't really need to change anything.

The Spamhaus blacklist is widely used, and it's widely used for one reason: contrary to STOPhaus's claims, it does, in fact, successfully block a lot of unwanted e-mail. There might be occasional collateral damage, but Spamhaus' users are clear: they're willing to take that risk if the alternative is more spam.

No comments:

Post a Comment