Obama officials refuse to say if assassination power extends to US soil

The administration's extreme secrecy is beginning to lead Senators to impede John Brennan's nomination to lead the CIA

Barack Obama announcing John Brennan as his choice to lead the CIA. Photograph: Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA

The Justice Department "white paper" purporting to authorize

Obama's power to extrajudicially execute US citizens was leaked three

weeks ago. Since then, the administration - including the president

himself and his nominee to lead the CIA, John Brennan

- has been repeatedly asked whether this authority extends to US soil,

i.e., whether the president has the right to execute US citizens on US

soil without charges. In each instance, they have refused to answer.

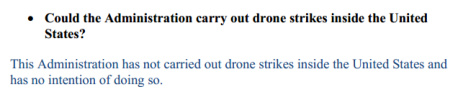

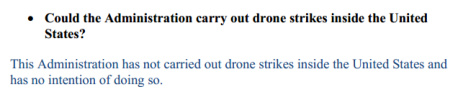

Brennan has been asked the question several times as part of his confirmation process. Each time, he simply pretends that the question has not been asked, opting instead to address a completely different issue. Here's the latest example from the written exchange he had with Senators after his testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee; after referencing the DOJ "white paper", the Committee raised the question with Brennan in the most straightforward way possible:

Obviously, that the US has not and does not intend to engage in such

acts is entirely non-responsive to the question that was asked: whether

they believe they have the authority to do so. To the extent any answer

was provided, it came in Brennan's next answer. He was asked:

Obviously, that the US has not and does not intend to engage in such

acts is entirely non-responsive to the question that was asked: whether

they believe they have the authority to do so. To the extent any answer

was provided, it came in Brennan's next answer. He was asked:

Revealingly, this same question was posed to Obama not by a journalist or a progressive but by a conservative activist, who asked if drone strikes could be used on US soil and "what will you do to create a legal framework to make American citizens within the United States believe know that drone strikes cannot be used against American citizens?" Obama replied that there "has never been a drone used on an American citizen on American soil" - which, obviously, doesn't remotely answer the question of whether he believes he has the legal power to do so. He added that "the rules outside of the United States are going to be different than the rules inside the United States", but these "rules" are simply political choices the administration has made which can be changed at any time, not legal constraints. The question - do you as president believe you have the legal authority to execute US citizens on US soil on the grounds of suspicions of Terrorism if you choose to do so? - was one that Obama, like Brennan, simply did not answer.

As always, it's really worth pausing to remind ourselves of how truly radical and just plainly unbelievable this all is. What's more extraordinary: that the US Senate is repeatedly asking the Obama White House whether the president has the power to secretly order US citizens on US soil executed without charges or due process, or whether the president and his administration refuse to answer? That this is the "controversy" surrounding the confirmation of the CIA director - and it's a very muted controversy at that - shows just how extreme the degradation of US political culture is.

As a result of all of this, GOP Senator Rand Paul on Thursday sent a letter to Brennan vowing to filibuster his confirmation unless and until the White House answers this question. Noting the numerous times this question was previously posed to Brennan and Obama without getting an answer, Paul again wrote:

After adding that "I believe the only acceptable answer to this is no", Paul wrote: "Until you directly and clearly answer, I plan to use every procedural option at my disposal to delay your confirmation and bring added scrutiny to this issue."

Yesterday, in response to my asking specifically about Paul's letter, Democratic Sen. Mark Udall of Colorado said that while he is not yet ready to threaten a filibuster, he "shares those concerns". He added: "Congress needs a better understanding of how the Executive Branch interprets the limits of its authorities."

Indeed it does. In fact, it is repellent to think that any member of the Senate Intelligence Committee - which claims to conduct oversight over the intelligence community - would vote to confirm Obama's CIA director while both the president and the nominee simply ignore their most basic question about what the president believes his own powers to be when it comes to targeting US citizens for assassination on US soil.

Udall also pointed to this New York Times article from yesterday detailing the growing anger on the part of several Democratic senators, including him, over the lack of transparency regarding the multiple legal opinions that purport to authorize the president's assassination power. Not only does the Obama administration refuse to make these legal memoranda public - senators have been repeatedly demanding for more than full year to see them - but they only two weeks ago permitted members to look at two of those memos, but "were available to be viewed only for a limited time and only by senators themselves, not their lawyers and experts." Said Udall in response to my questions yesterday: "Congress needs to fulfill its oversight function. This can't happen when members only have a short time to review complicated legal documents — as I did two weeks ago — and without any expert staff assistance or access to delve more deeply into the details."

Critically, the documents that are being concealed by the Obama administration are not operational plans or sensitive secrets. They are legal documents that, like the leaked white paper, simply purport to set forth the president's legal powers of execution and assassination. As Democratic lawyers relentlessly pointed out when the Bush administration also concealed legal memos authorizing presidential powers, keeping such documents secret is literally tantamount to maintaining "secret law". These are legal principles governing what the president can and cannot do - purported law - and US citizens are being barred from knowing what those legal claims are.

There is zero excuse for concealing these documents from the public (if there is any specific operational information, it can simply be redacted), and enormous harm that comes from doing so. As Dawn Johnsen, Obama's first choice to lead the OLC, put it during the Bush years: use of "'secret law' threatens the effective functioning of American democracy" and "the withholding from Congress and the public of legal interpretations by the [OLC] upsets the system of checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches of government." No matter your views on drones and War on Terror assassinations, what possible justification is there for concealing the legal rationale that authorizes these policies and defines the limits on the president's powers, if any?

You know who once claimed to understand the grave dangers from maintaining secret law? Barack Obama. On 16 April 2009, it was reported that Obama would announce whether he would declassify and release the Bush-era OLC memos that authorized torture. On that date, I wrote: "today is the most significant test yet determining the sincerity of Barack Obama's commitment to restore the Constitution, transparency and the rule of law." When it was announced that Obama would release those memos over the vehement objections of the CIA, I lavished him with praise for that, writing that "the significance of Obama's decision to release those memos - and the political courage it took - shouldn't be minimized". The same lofty reasoning Obama invoked to release those Bush torture memos clearly applies to his own assassination memos, yet his vaunted belief in transparency when it comes to "secret law" obviously applies only to George Bush and not himself.

The reason this matters so much has nothing to do with whether you think Obama is preparing to start assassinating US citizens on US soil. That's completely irrelevant to the question here. The reason this matters so much is because whatever presidential powers Obama establishes for himself become a permanent part of how the US government functions, and endures not only for the rest of his presidency but for subsequent ones as well.

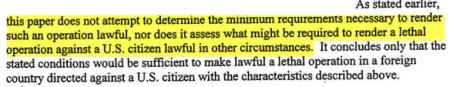

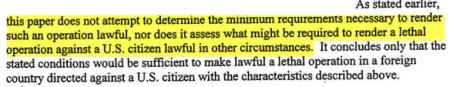

What is vital to realize is that the DOJ "white paper" absolutely does not answer the question of whether the assassination power it justified extends to US soil. That memo addressed the question of whether the president has the legal authority to target US citizens for assassination where "capture is infeasible" and concluded that he does, but that does not mean that it would be illegal to do so where capture is feasible. Contrary to the claims of some commentators, such as Steve Vladeck, it is impossible to argue reasonably that the memo imposed a requirement of "infeasibility of capture" on Obama's assassination power.

This could not be clearer: the DOJ memo expressly said that it was only addressing the issue of whether assassinations would be legal under the circumstances it was asked about, but that it was not opining on whether it would be legal in the absence of those circumstances. Just read its clear language in this regard: "This paper does not attempt to determine the minimum requirements necessary to render such an operation lawful." Again: the memo is not imposing "minimum requirements" on the president's assassination powers, such as the requirement that capture be infeasible. For those who did not process the first time, the memo - in its very last paragraph - emphasizes this again:

That's as conclusive as it gets: the DOJ white paper does not - does

not - answer the question of whether the president's assassination power

extends to US soil. It does not impose the requirement that capture

first be infeasible before the president can target someone for

execution. It expressly says it is imposing no such requirements. To the

contrary, it leaves open the question of whether the president has this

power where capture is feasible - including on US soil. That's

precisely why these senators are demanding an answer to this question:

because it's not answered in this memo. And that's precisely why the

White House refuses to answer: because it does not want to foreclose

powers that it believes it possesses, even if it has no current "intent"

to exercise those powers.

That's as conclusive as it gets: the DOJ white paper does not - does

not - answer the question of whether the president's assassination power

extends to US soil. It does not impose the requirement that capture

first be infeasible before the president can target someone for

execution. It expressly says it is imposing no such requirements. To the

contrary, it leaves open the question of whether the president has this

power where capture is feasible - including on US soil. That's

precisely why these senators are demanding an answer to this question:

because it's not answered in this memo. And that's precisely why the

White House refuses to answer: because it does not want to foreclose

powers that it believes it possesses, even if it has no current "intent"

to exercise those powers.

The crux of this issue goes to the heart of almost every civil liberties assault under the War on Terror since it began. Once you accept that the US is fighting a "war" against The Terrorists, and that the "battlefield" in this "war" has no geographical limitations, then you are necessarily vesting the president with unlimited powers. You're making him the functional equivalent of a monarch. That's because it is almost impossible to impose meaningful limitations on a president's war powers on a "battlefield".

If you posit that the entire world is a "battlefield", then you're authorizing him to do anywhere in the world what he can do on a battlefield: kill, imprison, eavesdrop, detain - all without limits or oversight or accountability. That's why "the-world-is-a-battlefield" theory was so radical and alarming (not to mention controversial) when David Addington, John Yoo and friends propagated it, and it's no less menacing now that it's become Democratic Party dogma as well.

Once you accept the premises of that DOJ white paper, there is no cogent limiting legal principle that would confine Obama's assassination powers to foreign soil. If "the whole world is a battlefield", then that necessarily includes US soil. The idea that assassinations will be used only where capture is "infeasible" is a political choice, not a legal principle. If the president has the power to kill anyone he claims is an "enemy combatant" in this "war", including a US citizen, then there is no way to limit this power to situations where capture is infeasible.

This was always the question I repeatedly asked of Bush supporters who embraced this same War on Terror theory to justify all of his claimed powers: how can any cognizable limits be placed on that power, including as applied to US citizens on US soil (and indeed, the Bush administration did apply that theory to those circumstances, as when it arrested US citizen Jose Padilla in Chicago and then imprisoned him for several years in a military brig in South Carolina: all without charges). They did so on the same ground used by Obama now: the whole world is a battlefield, so the president's power to detain people as "enemy combatants" is not geographically confined nor limited to foreign nationals.

Out of the good grace of his heart, or due to political expedience, Obama may decide to exercise this power only where he claims capture is infeasible, but there is no coherent legal reason that this power would be confined that way. The "global war" paradigm that has been normalized under two successive administrations all but compels that, as a legal matter, this power extend everywhere and to everyone. The only possible limitations are international law and the "due process" clause of the Constitution - and, in my view, that clearly bars presidential executions of US citizens no matter where they are as well as foreign nationals on US soil. But otherwise, once you accept the "global-battlefield" framework, then the scope of this presidential assassination power is limitless (this is to say nothing of how vague the standards in the DOJ "white paper" are when it comes to things like "imminence" and "feasibility of capture", as the New Yorker's Amy Davidson pointed out this week when suggesting that the DOJ white paper may authorize a president to kill US journalists who are preparing to write about leaks of national security secrets).

That this is even an issue - that this question even has to be asked and the president can so easily get away with refusing to answer - is a potent indicator of how quickly and easily even the most tyrannical powers become normalized. About all of this, Esquire's Charles Pierce yesterday put it perfectly:

But there's also a legal difference. As the Supreme Court has interpreted it, the US Constitution applies, roughly speaking, to two groups: (1) US citizens no matter where they are in the world, and (2) foreign nationals on US soil or US-controlled land (that's why foreign Guantanamo detainees had to argue that the US had sovereignty over Guantanamo Bay in order to invoke the US Constitution's habeas corpus guarantee against the US government). While international law certainly constraints what the US government may do to foreign nationals outside of land over which the US exercises sovereignty, the US Constitution, at least as the Supreme Court has interpreted it, does not. Moreover - not just for the US but for every nation - there is a unique danger that comes from a government acting repressively against its own citizens: that's what shields those in power from challenge and renders the citizenry pacified and afraid.

The US policy of killing or imprisoning anyone it wants, anywhere in the world, is immoral and wrong in equal measure when applied to US citizens and foreign nationals, on US soil or in Yemen and Pakistan. But application of the power to US citizens on US soil does raise distinct constitutional problems, creates the opportunity to mobilize the citizenry against it, and poses specific political dangers. That's why it is sometimes discussed separately.

Brennan has been asked the question several times as part of his confirmation process. Each time, he simply pretends that the question has not been asked, opting instead to address a completely different issue. Here's the latest example from the written exchange he had with Senators after his testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee; after referencing the DOJ "white paper", the Committee raised the question with Brennan in the most straightforward way possible:

Obviously, that the US has not and does not intend to engage in such

acts is entirely non-responsive to the question that was asked: whether

they believe they have the authority to do so. To the extent any answer

was provided, it came in Brennan's next answer. He was asked:

Obviously, that the US has not and does not intend to engage in such

acts is entirely non-responsive to the question that was asked: whether

they believe they have the authority to do so. To the extent any answer

was provided, it came in Brennan's next answer. He was asked: Could you describe the geographical limits on the Administration's conduct drone strikes?"Brennan's answer was that, in essence, there are no geographic limits to this power: "we do not view our authority to use military force against al-Qa'ida and associated forces as being limited to 'hot' battlefields like Afghanistan." He then quoted Attorney General Eric Holder as saying: "neither Congress nor our federal courts has limited the geographic scope of our ability to use force to the current conflict in Afghanistan" (see Brennan's full answer here).

Revealingly, this same question was posed to Obama not by a journalist or a progressive but by a conservative activist, who asked if drone strikes could be used on US soil and "what will you do to create a legal framework to make American citizens within the United States believe know that drone strikes cannot be used against American citizens?" Obama replied that there "has never been a drone used on an American citizen on American soil" - which, obviously, doesn't remotely answer the question of whether he believes he has the legal power to do so. He added that "the rules outside of the United States are going to be different than the rules inside the United States", but these "rules" are simply political choices the administration has made which can be changed at any time, not legal constraints. The question - do you as president believe you have the legal authority to execute US citizens on US soil on the grounds of suspicions of Terrorism if you choose to do so? - was one that Obama, like Brennan, simply did not answer.

As always, it's really worth pausing to remind ourselves of how truly radical and just plainly unbelievable this all is. What's more extraordinary: that the US Senate is repeatedly asking the Obama White House whether the president has the power to secretly order US citizens on US soil executed without charges or due process, or whether the president and his administration refuse to answer? That this is the "controversy" surrounding the confirmation of the CIA director - and it's a very muted controversy at that - shows just how extreme the degradation of US political culture is.

As a result of all of this, GOP Senator Rand Paul on Thursday sent a letter to Brennan vowing to filibuster his confirmation unless and until the White House answers this question. Noting the numerous times this question was previously posed to Brennan and Obama without getting an answer, Paul again wrote:

Do you believe that the President has the power to authorize lethal force, such as a drone strike, against a US citizen on US soil, and without trial?"

After adding that "I believe the only acceptable answer to this is no", Paul wrote: "Until you directly and clearly answer, I plan to use every procedural option at my disposal to delay your confirmation and bring added scrutiny to this issue."

Yesterday, in response to my asking specifically about Paul's letter, Democratic Sen. Mark Udall of Colorado said that while he is not yet ready to threaten a filibuster, he "shares those concerns". He added: "Congress needs a better understanding of how the Executive Branch interprets the limits of its authorities."

Indeed it does. In fact, it is repellent to think that any member of the Senate Intelligence Committee - which claims to conduct oversight over the intelligence community - would vote to confirm Obama's CIA director while both the president and the nominee simply ignore their most basic question about what the president believes his own powers to be when it comes to targeting US citizens for assassination on US soil.

Udall also pointed to this New York Times article from yesterday detailing the growing anger on the part of several Democratic senators, including him, over the lack of transparency regarding the multiple legal opinions that purport to authorize the president's assassination power. Not only does the Obama administration refuse to make these legal memoranda public - senators have been repeatedly demanding for more than full year to see them - but they only two weeks ago permitted members to look at two of those memos, but "were available to be viewed only for a limited time and only by senators themselves, not their lawyers and experts." Said Udall in response to my questions yesterday: "Congress needs to fulfill its oversight function. This can't happen when members only have a short time to review complicated legal documents — as I did two weeks ago — and without any expert staff assistance or access to delve more deeply into the details."

Critically, the documents that are being concealed by the Obama administration are not operational plans or sensitive secrets. They are legal documents that, like the leaked white paper, simply purport to set forth the president's legal powers of execution and assassination. As Democratic lawyers relentlessly pointed out when the Bush administration also concealed legal memos authorizing presidential powers, keeping such documents secret is literally tantamount to maintaining "secret law". These are legal principles governing what the president can and cannot do - purported law - and US citizens are being barred from knowing what those legal claims are.

There is zero excuse for concealing these documents from the public (if there is any specific operational information, it can simply be redacted), and enormous harm that comes from doing so. As Dawn Johnsen, Obama's first choice to lead the OLC, put it during the Bush years: use of "'secret law' threatens the effective functioning of American democracy" and "the withholding from Congress and the public of legal interpretations by the [OLC] upsets the system of checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches of government." No matter your views on drones and War on Terror assassinations, what possible justification is there for concealing the legal rationale that authorizes these policies and defines the limits on the president's powers, if any?

You know who once claimed to understand the grave dangers from maintaining secret law? Barack Obama. On 16 April 2009, it was reported that Obama would announce whether he would declassify and release the Bush-era OLC memos that authorized torture. On that date, I wrote: "today is the most significant test yet determining the sincerity of Barack Obama's commitment to restore the Constitution, transparency and the rule of law." When it was announced that Obama would release those memos over the vehement objections of the CIA, I lavished him with praise for that, writing that "the significance of Obama's decision to release those memos - and the political courage it took - shouldn't be minimized". The same lofty reasoning Obama invoked to release those Bush torture memos clearly applies to his own assassination memos, yet his vaunted belief in transparency when it comes to "secret law" obviously applies only to George Bush and not himself.

The reason this matters so much has nothing to do with whether you think Obama is preparing to start assassinating US citizens on US soil. That's completely irrelevant to the question here. The reason this matters so much is because whatever presidential powers Obama establishes for himself become a permanent part of how the US government functions, and endures not only for the rest of his presidency but for subsequent ones as well.

What is vital to realize is that the DOJ "white paper" absolutely does not answer the question of whether the assassination power it justified extends to US soil. That memo addressed the question of whether the president has the legal authority to target US citizens for assassination where "capture is infeasible" and concluded that he does, but that does not mean that it would be illegal to do so where capture is feasible. Contrary to the claims of some commentators, such as Steve Vladeck, it is impossible to argue reasonably that the memo imposed a requirement of "infeasibility of capture" on Obama's assassination power.

This could not be clearer: the DOJ memo expressly said that it was only addressing the issue of whether assassinations would be legal under the circumstances it was asked about, but that it was not opining on whether it would be legal in the absence of those circumstances. Just read its clear language in this regard: "This paper does not attempt to determine the minimum requirements necessary to render such an operation lawful." Again: the memo is not imposing "minimum requirements" on the president's assassination powers, such as the requirement that capture be infeasible. For those who did not process the first time, the memo - in its very last paragraph - emphasizes this again:

That's as conclusive as it gets: the DOJ white paper does not - does

not - answer the question of whether the president's assassination power

extends to US soil. It does not impose the requirement that capture

first be infeasible before the president can target someone for

execution. It expressly says it is imposing no such requirements. To the

contrary, it leaves open the question of whether the president has this

power where capture is feasible - including on US soil. That's

precisely why these senators are demanding an answer to this question:

because it's not answered in this memo. And that's precisely why the

White House refuses to answer: because it does not want to foreclose

powers that it believes it possesses, even if it has no current "intent"

to exercise those powers.

That's as conclusive as it gets: the DOJ white paper does not - does

not - answer the question of whether the president's assassination power

extends to US soil. It does not impose the requirement that capture

first be infeasible before the president can target someone for

execution. It expressly says it is imposing no such requirements. To the

contrary, it leaves open the question of whether the president has this

power where capture is feasible - including on US soil. That's

precisely why these senators are demanding an answer to this question:

because it's not answered in this memo. And that's precisely why the

White House refuses to answer: because it does not want to foreclose

powers that it believes it possesses, even if it has no current "intent"

to exercise those powers.The crux of this issue goes to the heart of almost every civil liberties assault under the War on Terror since it began. Once you accept that the US is fighting a "war" against The Terrorists, and that the "battlefield" in this "war" has no geographical limitations, then you are necessarily vesting the president with unlimited powers. You're making him the functional equivalent of a monarch. That's because it is almost impossible to impose meaningful limitations on a president's war powers on a "battlefield".

If you posit that the entire world is a "battlefield", then you're authorizing him to do anywhere in the world what he can do on a battlefield: kill, imprison, eavesdrop, detain - all without limits or oversight or accountability. That's why "the-world-is-a-battlefield" theory was so radical and alarming (not to mention controversial) when David Addington, John Yoo and friends propagated it, and it's no less menacing now that it's become Democratic Party dogma as well.

Once you accept the premises of that DOJ white paper, there is no cogent limiting legal principle that would confine Obama's assassination powers to foreign soil. If "the whole world is a battlefield", then that necessarily includes US soil. The idea that assassinations will be used only where capture is "infeasible" is a political choice, not a legal principle. If the president has the power to kill anyone he claims is an "enemy combatant" in this "war", including a US citizen, then there is no way to limit this power to situations where capture is infeasible.

This was always the question I repeatedly asked of Bush supporters who embraced this same War on Terror theory to justify all of his claimed powers: how can any cognizable limits be placed on that power, including as applied to US citizens on US soil (and indeed, the Bush administration did apply that theory to those circumstances, as when it arrested US citizen Jose Padilla in Chicago and then imprisoned him for several years in a military brig in South Carolina: all without charges). They did so on the same ground used by Obama now: the whole world is a battlefield, so the president's power to detain people as "enemy combatants" is not geographically confined nor limited to foreign nationals.

Out of the good grace of his heart, or due to political expedience, Obama may decide to exercise this power only where he claims capture is infeasible, but there is no coherent legal reason that this power would be confined that way. The "global war" paradigm that has been normalized under two successive administrations all but compels that, as a legal matter, this power extend everywhere and to everyone. The only possible limitations are international law and the "due process" clause of the Constitution - and, in my view, that clearly bars presidential executions of US citizens no matter where they are as well as foreign nationals on US soil. But otherwise, once you accept the "global-battlefield" framework, then the scope of this presidential assassination power is limitless (this is to say nothing of how vague the standards in the DOJ "white paper" are when it comes to things like "imminence" and "feasibility of capture", as the New Yorker's Amy Davidson pointed out this week when suggesting that the DOJ white paper may authorize a president to kill US journalists who are preparing to write about leaks of national security secrets).

That this is even an issue - that this question even has to be asked and the president can so easily get away with refusing to answer - is a potent indicator of how quickly and easily even the most tyrannical powers become normalized. About all of this, Esquire's Charles Pierce yesterday put it perfectly:

"This is why the argument many liberals are making - that the drone program is acceptable both morally and as a matter of practical politics because of the faith you have in the guy who happens to be presiding over it at the moment -- is criminally naive, intellectually empty, and as false as blue money to the future. The powers we have allowed to leach away from their constitutional points of origin into that office have created in the presidency a foul strain of outlawry that (worse) is now seen as the proper order of things.That language may sound extreme. But it's actually mild when set next to the powers that the current president not only claims but has used. The fact that he does it all in secret - insists that even the "law" that authorizes him to do it cannot be seen by the public - is precisely why Pierce is so right when he says that "the very nature of the presidency of the United States at its core has become the vehicle for permanently unlawful behavior". To allow a political leader to claim those kinds of of powers, and to exercise them in secret, guarantee chronic criminality.

"If that is the case, and I believe it is, then the very nature of the presidency of the United States at its core has become the vehicle for permanently unlawful behavior. Every four years, we elect a new criminal because that's become the precise job description."

Targeting US citizens v. foreign nationals

Whenever this issue is raised, people quite reasonably ask why there should be any difference in the reaction to targeting US citizens as opposed to foreign nationals. As a moral and ethical matter, and as a matter of international law, there is no difference whatsoever. I am every bit as opposed to targeting foreign nationals for due-process-free assassinations as I am US citizens, which is why I have devoted so much time and energy to opposing that policy. I also agree entirely with what Desmond Tutu recently said in response to calls for a special secret "court" to be created to review the targeting of US citizens for assassinations:"Do the United States and its people really want to tell those of us who live in the rest of the world that our lives are not of the same value as yours? That President Obama can sign off on a decision to kill us with less worry about judicial scrutiny than if the target is an American? Would your Supreme Court really want to tell humankind that we, like the slave Dred Scott in the 19th century, are not as human as you are? I cannot believe it.But the explanation for why the targeting of US citizens receives distinct attention is two-fold: both political and legal. Politically, it is simply easier to induce one's fellow citizens to care about an abusive power if you can persuade them that it will affect them and not merely those Foreign Others. It shouldn't be that way, but the reality of human nature is that it is (recall how civil liberties and privacy concerns catapulted to the top of the news when US citizens generally - not just Muslims - were subjected to new invasive airport searches). So emphasizing that the assassination power extends to US citizens as well as foreign nationals can be an important instrument in battling indifference.

"I used to say of apartheid that it dehumanized its perpetrators as much as, if not more than, its victims. Your response as a society to Osama bin Laden and his followers threatens to undermine your moral standards and your humanity."

But there's also a legal difference. As the Supreme Court has interpreted it, the US Constitution applies, roughly speaking, to two groups: (1) US citizens no matter where they are in the world, and (2) foreign nationals on US soil or US-controlled land (that's why foreign Guantanamo detainees had to argue that the US had sovereignty over Guantanamo Bay in order to invoke the US Constitution's habeas corpus guarantee against the US government). While international law certainly constraints what the US government may do to foreign nationals outside of land over which the US exercises sovereignty, the US Constitution, at least as the Supreme Court has interpreted it, does not. Moreover - not just for the US but for every nation - there is a unique danger that comes from a government acting repressively against its own citizens: that's what shields those in power from challenge and renders the citizenry pacified and afraid.

The US policy of killing or imprisoning anyone it wants, anywhere in the world, is immoral and wrong in equal measure when applied to US citizens and foreign nationals, on US soil or in Yemen and Pakistan. But application of the power to US citizens on US soil does raise distinct constitutional problems, creates the opportunity to mobilize the citizenry against it, and poses specific political dangers. That's why it is sometimes discussed separately.

No comments:

Post a Comment