Big Bro is watching you. Inside your mobile phone and hidden behind

your web browser are little known software products marketed by

contractors to the government that can follow you around anywhere. No

longer the wide-eyed fantasies of conspiracy theorists, these

technologies are routinely installed in all of our data devices by

companies that sell them to Washington for a profit.

That’s not how they’re marketing them to us, of course. No, the

message is much more seductive: data, Silicon Valley is fond of saying,

is the new oil. And the Valley’s message is clear enough: we can turn

your digital information into fuel for pleasure and profits—if you just

give us access to your location, your correspondence, your history, and

the entertainment that you like.

Ever played Farmville? Checked into Foursquare? Listened to music on

Pandora? These new social apps come with an obvious price tag: the

annoying advertisements that we believe to be the fee we have to pay for

our pleasure. But there’s a second, more hidden price tag—the reams of

data about ourselves that we give away. Just like raw petroleum, it can

be refined into many things—the high-octane jet fuel for our social

media and the asphalt and tar of our past that we would rather hide or

forget.

We

willingly hand over all of this information to the big data companies

and in return they facilitate our communications and provide us with

diversions. Take Google, which offers free email, data storage, and

phone calls to many of us, or Verizon, which charges for smartphones and

home phones. We can withdraw from them anytime, just as we believe that

we can delete our day-to-day social activities from Facebook or

Twitter.

But there is a second kind of data company of which most people are

unaware: high-tech outfits that simply help themselves to our

information in order to allow U.S. government agencies to dig into our

past and present. Some of this is legal, since most of us have signed

away the rights to our own information on digital forms that few ever

bother to read, but much of it is, to put the matter politely,

questionable.

This second category is made up of professional surveillance

companies. They generally work for or sell their products to the

government—in other words, they are paid with our tax dollars—but we

have no control over them. Harris Corporation provides technology to the

FBI to track, via our mobile phones, where we go; Glimmerglass builds

tools that the U.S. intelligence community can use to intercept overseas

calls; and companies like James Bimen Associates design software to

hack into our computers.

There is also a third category: data brokers like Arkansas-based

Acxiom. These companies monitor our Google searches and sell the

information to advertisers. They make it possible for Target to offer

baby clothes to pregnant teenagers, but also can keep track of your

reading habits and the questions you pose to Google on just about

anything from pornography to terrorism—presumably to sell you Viagra and

assault rifles.

Locating You

Edward Snowden has done the world a great service by telling us what

the National Security Agency does and how it has sweet-talked and

bullied the first category of companies into handing over our data. As a

result, perhaps you’ve considered switching providers from AT&T to

T-Mobile or Dropbox to the more secure Spider- Oak. After all, who wants

some anonymous government bureaucrat listening in on or monitoring your

online and phone life?

Missing

from this debate, however, have been the companies that get contracts

to break into our homes in broad daylight and steal all our information

on the taxpayer’s dime. We’re talking about a multi-billion dollar

industry whose tools are also available for those companies to sell to

others or even use them for profit or vicarious pleasure. So just what

do these companies do and who are they?

The simplest form of surveillance technology is an IMSI catcher.

(IMSI stands for International Mobile Subscriber Identity, which is

unique to every mobile phone.) These highly portable devices pose as

mini-mobile phone towers and can capture all the mobile-phone signals in

an area. In this way, they can effectively identify and locate all

phone users in a particular place. Some are small enough to fit into a

briefcase, others are no larger than a mobile phone. Once deployed, the

IMSI catcher tricks phones into wirelessly sending it data.

By setting up several IMSI catchers in an area and measuring the

speed of the responses or “pings” from a phone, an analyst can follow

the movement of anyone with a mobile phone even when they are not in

use.

One of the key players in this field is the Melbourne, Florida-based

Harris Corporation, which has been awarded almost $7 million in public

contracts by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) since 2001,

mostly for radio communication equipment. For years, the company has

also designed software for the agency’s National Crime Information

Center to track missing persons, fugitives, criminals, and stolen

property.

Harris

was recently revealed to have designed an IMSI catcher for the FBI that

the company named “Stingray.” Court testimony by FBI agents has

confirmed the existence of the devices dating back to at least 2002.

Other companies like James Bimen Associates of Virginia have allegedly

designed custom software to help the FBI hack into people’s computers,

according to research by Chris Soghoian of the American Civil Liberties

Union (ACLU).

The FBI has not denied this. The Bureau “hires people who have

hacking skill, and they purchase tools that are capable of doing these

things,” a former official in the FBI’s cyber division told the

Wall Street Journal recently. “When you do, it’s because you don’t have any other choice.”

The technologies these kinds of companies exploit often rely on

software vulnerabilities. Hacking software can be installed from a USB

drive, or delivered remotely by disguising it as an email attachment or

software update. Once in place, an analyst can rifle through a target’s

files, log every keystroke, and take pictures of the screen every

second. For example, SS8 of Milpitas, California, sells software called

Intellego that claims to allow government agencies to “see what [the

targets] see, in real time” including “draft-only emails, attached

files, pictures, and videos.” Such technology can also remotely turn on

phone and computer microphones, as well as computer or cellphone cameras

to spy on the target in real-time.

Charting You

What the FBI does, however intrusive, is small potatoes compared to

what the National Security Agency dreams of doing: getting and storing

the data traffic not just of an entire nation, but of an entire planet.

This became a tangible reality some two decades ago as the

telecommunications industry began mass adoption of fiber-optic

technology. This means that data is no longer transmitted as electrical

signals along wires that were prone to interference and static, but as

light beams.

Enter companies like Glimmerglass, yet another northern California

outfit. In September 2002, Glimmerglass started to sell a newly patented

product consisting of 210 tiny gold-coated mirrors mounted on

microscopic hinges etched on to a single wafer of silicon. It can help

transmit data as beams of light across the undersea fiber optic cables

that carry an estimated 90 percent of trans-border telecommunications

data. The advantage of this technology is that it is dirt cheap and—for

the purposes of the intelligence agencies—the light beams can easily be

copied with almost no noticeable loss in quality.

“With Glimmerglass Intelligent Optical Systems (IOS), any signal

travelling over fiber can be redirected in milliseconds, without

adversely affecting customer traffic,” says the company on its public

website.

Glimmerglass does not deny that its equipment can be used by

intelligence agencies to capture global Internet traffic. In fact, it

assumes that this is probably happening. “We believe that our 3D MEMS

technology—as used by governments and various agencies—is involved in

the collection of intelligence from sensors, satellites, and undersea

fiber systems,” Keith May, Glimmerglass’s director of business

development, told the trade magazine

Aviation Week in 2010. “We are deployed in several countries that are using it for lawful interception.”

In a confidential brochure, Glimmerglass has a series of graphics

that, it claims, show just what its software is capable of. One displays

a visual grid of the Facebook messages of a presumably fictional “John

Smith.” His profile is linked to a number of other individuals

(identified with images, user names, and IDs) via arrows indicating how

often he connected to each of them. A second graphic shows a grid of

phone calls made by a single individual that allows an operator to

select and listen to audio of any of his specific conversations. Yet

others display Glimmerglass software being used to monitor webmail and

instant message chats.

“The challenge of managing information has become the challenge of

managing the light,” says an announcer in a company video on their

public website. “With Glimmerglass, customers have full control of

massive flows of intelligence from the moment they access them.”

This description mirrors technology described in documents provided by Edward Snowden to the

Guardian newspaper.

Predicting You

Listening to phone calls, recording locations, and breaking into

computers are just one part of the tool kit that the data-mining

companies offer to U.S. (and other) intelligence agencies. Think of them

as the data equivalents of oil and natural gas drilling companies that

are ready to extract the underground riches that have been stashed over

the years in strongboxes in our basements.

What government agencies really want, however, is not just the

ability to mine, but to refine those riches into the data equivalent of

high-octane fuel for their investigations in very much the way we

organize our own data to conduct meaningful relationships, find

restaurants, or discover new music on our phones and computers.

These technologies—variously called social network analysis or

semantic analysis tools—are now being packaged by the surveillance

industry as ways to expose potential threats that could come from

surging online communities of protesters or anti-government activists.

Take Raytheon, a major U.S. military manufacturer, which makes

Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, Maverick air-to- ground missiles,

Patriot surface-to-air missiles, and Tomahawk submarine-launched cruise

missiles. Their latest product is a software package eerily named “Riot”

that claims to be able to predict where individuals are likely to go

next using technology that mines data from social networks like

Facebook, Foursquare, and Twitter.

Raytheon’s Rapid Information Overlay Technology software—yes, that’s

how they got the acronym Riot—extracts location data from photos and

comments posted online by individuals and analyzes this information. The

result is a variety of spider diagrams that purportedly will show where

that individual is most likely to go next, what she likes to do, and

whom she communicates with or is most likely to communicate with in the

near future.

A 2010 video demonstration of the software was recently published online by the

Guardian.

In it, Brian Urch of Raytheon shows how Riot can be used to track

“Nick”—a company employee—in order to predict the best time and place to

steal his computer or put spy software on it. “Six a.m. appears to be

the most frequently visited time at the gym,” says Urch. “So if you ever

did want to try to get a hold of Nick—or maybe get a hold of his

laptop—you might want to visit the gym at 6:00 a.m. on Monday.”

“Riot is a big data analytics system design we are working on with

industry, national labs, and commercial partners to help turn massive

amounts of data into useable information to help meet our nation’s

rapidly changing security needs,” Jared Adams, a spokesman for

Raytheon’s intelligence and information systems department, told the

Guardian.

The company denies that anyone has yet bought Riot, but U.S. government

agencies certainly appear more than eager to purchase such tools.

For example, in January 2012 the FBI posted a request for an app that

would allow it to “provide an automated search and scrape capability of

social networks including Facebook and Twitter and [i]mmediately

translate foreign language tweets into English.” In January 2013, the

U.S. Transportation Security Administration asked contractors to propose

apps “to generate an assessment of the risk to the aviation

transportation system that may be posed by a specific individual” using

“specific sources of current, accurate, and complete non-governmental

data.”

Privacy activists say that the Riot package is troubling indeed.

“This sort of software allows the government to surveil everyone,”

Ginger McCall, the director of the Electronic Privacy Information

Center’s Open Government program, told NBC News. “It scoops up a bunch

of information about totally innocent people. There seems to be no

legitimate reason to get this.”

Refining fuel from underground deposits has allowed us to travel vast

distances by buses, trains, cars, and planes for pleasure and profit

but at an unintentional cost: the gradual warming of our planet.

Likewise, the refining of our data into social apps for pleasure,

profit, and government surveillance is also coming at a cost: the

gradual erosion of our privacy and ultimately our freedom of speech.

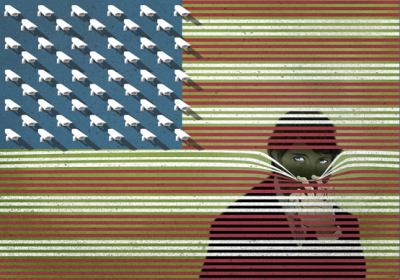

Ever tried yelling back at a security camera? You know that it is on.

You know someone is watching the footage, but it doesn’t respond to

complaint, threats, or insults. Instead, it just watches you in a

forbidding manner. Today, the surveillance state is so deeply enmeshed

in our data devices that we don’t even scream back because technology

companies have convinced us that we need to be connected to them to be

happy.

With a lot of help from the surveillance industry, Big Bro has

already won the fight to watch all of us all the time—unless we decide

to do something about it.

Pratap Chatterjee, a TomDispatch regular, is

executive director of CorpWatch and a board member of Amnesty

International USA. He is the author of Halliburton’s Army(Nation Books)

and Iraq, Inc. This article first appeared on TomDispatch. com, a weblog

of the Nation Institute, which offers news, and opinion from Tom

Engelhardt.

While

anti-piracy actions take place all around the world on a daily basis,

it is relatively rare to hear of targeted lawsuits against individual

sites. But as the MPAA case against isoHunt closes, another large one is developing in its wake.

While

anti-piracy actions take place all around the world on a daily basis,

it is relatively rare to hear of targeted lawsuits against individual

sites. But as the MPAA case against isoHunt closes, another large one is developing in its wake.